Baku and the Soviet Heritage: Memory and Oblivion

The collapse of the Soviet Union launched the search for a new identity and the creation of new narratives in Azerbaijan just as in the entire ex-Soviet space. We cannot cover all aspects of the memory politics in Azerbaijan during and after the Soviet period in a single article. Instead, we highlight the most significant sites of the Soviet memory landscape of Baku and their post-Soviet transformations within the new politics of memory.

The Nagorny Park Named After Sergey Kirov

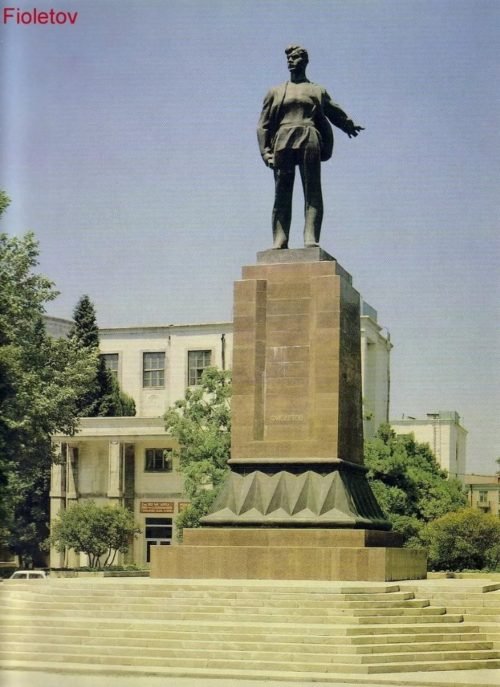

The monument to Sergey Kirov. Location: Nagorny Park, Baku, Azerbaijan. Date of the Photo: 1978. Photo Credits: Isaac Rubenchik, taken from ourbaku.com.

Immediately after the Sovietization of Azerbaijan, the urban development of Baku took a Soviet turn. In September 1920, the special committee on the development of city gardens in the Absheron peninsula created a plan on changing the appearance of the city. It included the development of the English Park in the place of the Chemberkent cemetery[1]. Later it became part of the Nagorny[2] Park.

In 1939, the Nagorny Park took the name of Sergey Kirov, a prominent political figure whose death of at the end of 1934 had made him one of the central heroes of the politics of memory of Soviet Azerbaijan[3]. Kirov’s monument was installed in the Nagorny Park as the latter dominated the panorama of Baku with a view on the bay. Kirov’s massive figure raising his hand over the city was placed at the center of a memorial that remained a prominent landmark of Baku until the collapse of the Soviet Union (Bertanitski 1971, 138-140).

The Architectural Complex Lenin Square

The design of Baku’s new central square began with the construction of the House of the Soviets (“Dom Sovietov” in Russian) or the Government House. Intended to accommodate large-scale events and serve the purpose of an ideological center, the square was the largest one in the USSR at the time of its completion (Bertanitski 1971, 146-149).

The Government House. Location: Then Lenin Sqaure, Baku, Azerbaijan. Date of the Photo: 1977-80. Photo Credits: Leonid Kondratyev, taken from pastvu.com.

The construction of the House began in 1930 and was completed in 1952. According to the architects of the House, the exterior of the building was designed in the Baroque style, using also elements of the national Azerbaijani architecture. This style was reflected in the three rows of columns located along the edges of the building, the prototype for which was the colonnade of the reception hall of the medieval Shirvanshah palace in Baku. The construction of the adjacent Lenin Square ended in the Fall of 1951. It became an ideal location for military parades and demonstrations of workers. The first large-scale event took place on November 7 of 1951 on the commemoration of the October Revolution of Bolsheviks.

The House of the Soviets itself was designed as a “memorial-building” dedicated to the “father of the revolution” Vladimir Lenin. His monument was installed in the square on November 6 of 1954. For many years, the expressive 11-meter bronze sculpture of Lenin, the leader of the proletariat, portrayed at the time of addressing the people, was the central element of the whole complex. The last Soviet demonstration in the square took place in May 1987. The mass rallies in the following years went down history as the events that contributed to the collapse of the USSR.

The 26 Baku Commissars Square

26 Baku Commissars Memorial. Location: Baku, Azerbaijan. Date of the Photo: 1980. Photo Credits: taken from commons.wikimedia.com.

On September 10 of 1920, a solemn ceremony of reburial was taking place in the Freedom Square (the former Stock Exchange Square or “Birzhevaya” in Russian) of Baku. The remains of the Baku Commune members were brought from Krasnovodsk, where they had been executed by a firing squad in 1918. Since then, they have been referred to as the “26 Baku Commissars”, with the Soviet propaganda putting upon them a halo of martyrdom and turning their story into an important Soviet historical and ideological narrative. The four main commissars, Meshadi Azizbekov, Prokofy (Alyosha) Dzhaparidze, Stepan Shahumyan, and Ivan Fioletov, with their respective backgrounds of an Azerbaijani, a Georgian, an Armenian, and a Russian, were to symbolize the international spirit of Baku. The Soviet ideology turned their burial site into a place of memory and glorification.

The square and the park around it went through several transformations and were renamed after the 26 Baku Commissars. The first memorial was constructed in 1923 in time for the fifth anniversary of the commissars’ death. For the 40th anniversary in 1958, a high relief sculpture, the “Execution of the 26 Baku Commissars” was installed in the park. In another ten years, the entire site went through a redesign. The Eternal Flame was added and the structure made of marble, reinforced concrete, and granite was erected above the graves, creating a ring-shaped pantheon. The structure was inscribed with the words “26 Bakı Komissarı”. A massive bust of an oilman bent over the Eternal Flame was placed in the center of the composition.

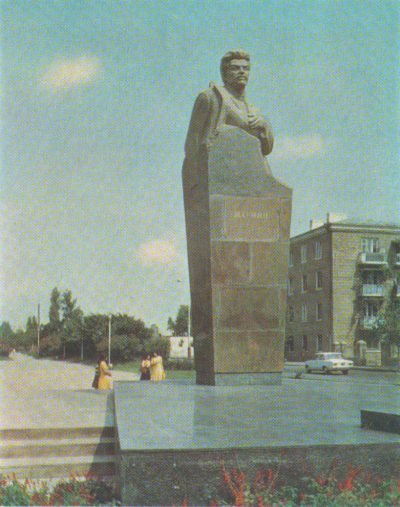

In the Soviet politics of memory, the cult of the commissars took up an extremely important place as a symbol of proletarian internationalism and a selfless struggle against oppression. In the 1970s and 80s, in addition to this memorial complex, personal monuments to some of the commissars were established in different parts of Baku – in 1975 to Stepan Shahumyan, in 1976 to Meshadi Azizbekov, in 1980 to Prokofy Dzhaparidze, and in 1985 to Ivan Fioletov.

The Collapse of Ideals: The Alley of Martyrs in Nagorny Park and the New Freedom Square

The collapse of the Soviet Union, which coincided with the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, led to a dramatic reconstruction of Baku’s memory landscape. The Baku residents who were killed during the tragic events of January 1990[4] were buried in the Nagorny Park[5]. A grandiose funeral demonstration began on Lenin Square, transferring the bodies of the dead to the territory of the park, that from that moment on, became the site of the Alley of Martyrs (“Şəhidlər Xiyabanı” in Azerbaijani).

Kirov’s memorial was demolished in 1991. Later the graves of the heroes of the Nagorno-Karabakh war of 1992-1994 were also placed here. Regardless of when they died, those buried here are called martyrs. This is a religious term applied to people who died for their faith, and in a broader sense, for a just cause – in this case, for the independence and territorial integrity of the country. The grand opening of the memorial complex of the Eternal Flame took place on October 9 of 1998. Currently, the ally continues to serve as a reminder of Azerbaijan’s Soviet past, but now exclusively in a negative sense – as a period of oppression and deprivation of independence that was restored thanks to the martyrs buried here.

The January 1990 tragedy in Baku became a point of no return. The more heated the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh became, the louder the nationalist slogans got, which, in turn, further fueled the conflict. The later events of the Nagorno-Karabakh war, as well as the explicit and implicit Russian assistance to Armenia, gave momentum to the discourse of Soviet oppression and antagonism with it. As a result, everything Soviet, Russian, and Armenian was declared alien and subject to demolition and distancing. In a new Azerbaijan, the Soviet monuments were perceived to embody the crimes of Russians and Armenians towards the Azerbaijani people and the loss of independence. The “fight” against these monuments inevitably became an important part of the de-Sovietization that was already underway.

One of the first monuments to disappear from the streets of Baku in 1990 was the bust of Stepan Shahumyan[6] . With the transition to independence, the head of the Baku Commune had become nothing but the worst enemy of Azerbaijanis and a hidden Dashnak – affiliated with the nationalist Armenian Revolutionary Federation Party (“Dashnaktsutyun” in Armenian).

Immediately after the failed attempt of the August 1991 Coup in Moscow, Lenin Square was renamed into Freedom Square (“Azadlıq Meydanı” in Azerbaijani). Soon after that, Lenin’s statue in front of the Government House was demolished, and the state flag of Azerbaijan was erected in its place. The square kept its status of the central square in the country and was now associated with the fight for independence. Military parades continue to take place here nowadays. The first one took place in October of 1992, and the latest one was in June 2018.

The New Interpretation of the Soviet Past

On October 18 of 1991, the Constitutional Act on the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan, signed by President Ayaz Mutalibov, became the document laying out the foundation of the official politics of memory in independent Azerbaijan. It referred to centuries-long traditions of statehood of the Azerbaijani people and the Russian aggression towards Azerbaijan in 1920. The document described the seventy years of the Soviet rule as a period of colonialism, a ruthless exploitation of natural resources and plunder of national wealth, and infringement on national dignity.

This reinterpretation of the Soviet past was also derived from the context of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and was sealed by its consequences. It reflected the vision of history of the nationalists from the Popular Front Party of Azerbaijan (“Azərbaycan Xalq Cəbhəsi Partiyası” in Azerbaijani). However, this approach remained the cornerstone of the public consensus also under the leadership of President Heydar Aliyev. Later, it gained a fresh momentum in the form of another wave of de-Sovietization under President Ilham Aliyev. Heydar Aliyev’s decree “On the Genocide of Azerbaijanis”, adopted in 1998 for the bloody events of March 1918, was also an important landmark of the de-Sovietization process.

The dismantling of memorial plaques was the latest stage of de-Sovietization, as a policy to put the Soviet past to oblivion. For example, the Soviet plaque “Palace of Happiness” was removed from the Palace of Marriage Registrations during its reconstruction. The plaque also noted that the building used to house the Women’s Club named after Ali Bayramov and that the Club played an important role in the “emancipation of the Azerbaijani woman”. Similarly, after the reconstruction of the Nizami Cinema Center, the memorial plaque that indicated that the cinema received a commemorative banner did not find a place on its walls.

The Sahil Park in the Place of the 26 Baku Commissars

The demolition of the memorial complex of the 26 Baku Commissars began in the early 1990s. First, the Eternal Flame was put out, and then in 1993, the high relief sculpture “The Execution of the Baku Commissars” was destroyed. The inscription “26 Bakı Komissarı” was removed from the pantheon, and the area was renamed into Sahil Park.

For many years, the memorial remained abandoned. Stripped of its usual symbolism, the pantheon over the graves of commissars in the center of the city was creating an obvious dissonance. Finally, in January 2009, the park was closed for reconstruction. The structure around the Eternal Flame was demolished, and the remains of the commissars were reburied in the Hovsan cemetery in the suburbs of Baku. The renovated the Sahil Park, with a three-tier fountain installed in the middle, opened in May 2009.

The fountain in Sahil Park built in the place of 26 Baku Commissars memorial. Location: Baku, Azerbaijan. Date of the Photo: February 5, 2018. Photo Credit: Saadat Abdullazade.

As noted above, with the wind of change, the monument to the Armenian commissar Stepan Shahumyan was the first one demolished in 1990. In 1992, the monument to the Russian commissar Ivan Fioletov followed. Monuments to the Azerbaijani Meshadi Azizbekov and Georgian Prokofy Dzhaparidze stayed significantly longer and were demolished only in 2009 on the night of April 26 and 28 respectively.

The authorities react fervently to the slightest attempt at the revival of the symbolism associated with the commissars and the former name of the park. In 2017, the café “26” near the Sahil Park was closed by the city authorities, and their property was confiscated. The owners of the café were blamed for fulfilling an “Armenian order” and speculated to have family ties with the deceased commissars of Armenian origin.

The “Untouchable” Narimanov

Among the monuments to the Soviet state and its party leaders, there is one that survived all the stages of de-Sovietization and de-communization. It is the monument to Nariman Narimanov. He was the de facto leader of Soviet Azerbaijan during the first half of the 1920s when the first anti-Soviet armed demonstrations were suppressed. Through his participation in the central structures of the Soviet state, Narimanov also cemented the Soviet ideology of internationalism, which in modern Azerbaijan is viewed nothing more than a way of Russian and Armenian dominance over the indigenous population – the Azerbaijanis. Then how did Narimanov’s monument survive de-Sovietization?

The monument to Nariman Narimanov. Location: Baku, Azerbaijan. Date of the Photo: February 6, 2018. Photo Credits: Saadat Abdullazade.

The new official discourse in independent Azerbaijan claimed that people had been fighting for independence throughout the Soviet period. And it was this persistent struggle, carried forward despite Moscow’s policy, that explains any achievement and success of the Soviet period. The argument is that despite Moscow’s anti-national policies, the Azerbaijani identity was preserved thanks to local political leaders whose national-patriotic spirit outweighed their adherence to Soviet ideology. Thus, their legacy is still honored as they are believed to have done everything possible to protect Azerbaijan’s interests. This clause of “despite” allows the selective attitude towards the monuments of the Soviet political leaders, and Narimanov is one of them.

Narimanov is credited for keeping Nakhijevan and Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan in the 1920s. It is widely believed that he was the one who saved prominent Azerbaijani generals Samed Mehmandarov and Aliagha Shikhlinski from Bolshevik repressions. He is portrayed as the politician who blocked the demands of Armenian nationalists acting under the patronage of Russian Bolsheviks. More recently, theories have appeared suggesting that Narimanov was deliberately pushed out of Baku and later poisoned in Moscow. Articles and books defending his ideas have been published. And the large-scale monument to Narimanov put up in 1972 continues to stand in one of the Baku squares.

Between Memory and Oblivion

The monuments, memorials, and places of memory discussed in this article appear to us as the most significant in the context of Soviet politics of memory and its post-Soviet transformations. Nevertheless, many other memorials were produced both in Soviet and independent Azerbaijan, and one article cannot cover them all. It is noteworthy that a number of monuments related to the Second World War (or its Soviet “equivalent” of the Great Patriotic War) have been completely preserved. At the same time, “that war” has largely lost its significance and ceded its memory to the events around the collapse of the Soviet Union and the current Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. As a result, the monuments, memorials, and places of memory, created for the commemoration of the “Black January” of 1990 or the Khojaly tragedy[7] , currently occupy a central place in the modern memory landscape in Azerbaijan.

Footnotes

[1] The Chemberkent cemetery was also the burial site of the British soldiers who died during the civil war of 1918 in Baku. That’s why initially the park was often called “English”.

[2] “Nagorny” means “upland” in Russian, and the park was named so because it is situated on a high platform in Baku.

[3] As a member of the 11th Unit of the Red Army, Kirov had taken part in the establishment of Soviet power in Baku. Later he was elected First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan.

[4] On the events of January 1990, see the 2003 book of Thomas De Waal “Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war” published by New York University Press.

[5] This decision might have been motivated by the fact that the Chemberkent cemetery used to be located here. It was believed that the Muslim victims of the bloody events of March 1918 in Baku were buried here. And indeed, during the ground preparations for the burial of the victims of January 1990, the remains of three people were found in the park and were reburied. The tombstones indicate that these are the “martyrs of 1918”. For more details on these events, see the 2010 translation into Russian of the book by Jörg Baberovski “The Enemy is Everywhere: Stalinism in the Caucasus” («Враг есть везде: Сталинизм на Кавказе») published by Rosspen in Moscow.

[6] For the biography of Stepan Shahumyan, see the 2012 work of Eldar Ismailov “Stepan Shahumyan – doomed to oblivion: a portrait of the “legendary communard” without retouching” («Степан Шаумян – обреченный на забвение – портрет «легендарного коммунара» без ретуши») published by Sharg-Garb publishing house in Baku.

[7] For more on the Khojaly tragedy, see the 2003 book of Thomas De Waal “Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war” published by New York University Press.

Bibliography

Bertanitski, Leonid. 1971. Баку [Baku]. Leningrad-Moscow: Iskusstvo.

* This story has been produced with support from the US Embassies in the South Caucasus. The opinions expressed in the publication reflect the point of the view of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the US Embassies.

** This story is part of a series on post-Soviet transformations of the memory landscapes, memorial sites, and monuments in Tbilisi, Yerevan, and Baku.

Archived comments

Thank you very much for such an interesting article!

Very interesting! Thanks so much, I will go there in summer, this post helped me! congratulations, great job!