In the heart of Yerevan, on Firdusi street, there is a stone house dating back to the second half of the 19th century. The foundation has taken roots in the ground, but even in the ear of rapid gentrification[1] and rapid destruction of the Soviet and pre-Soviet architectural segment of the city, this building stays intact.

The lady of the house opens the door:

“Klara Melkumyan, – she introduces herself with laughter and adds; -Melkumyan-Kocharyan. I have two last names, please come in.”

Two last names, two homes, two homelands, two stories of family memory, several languages. This house is a memory of a tragic past that casts a shadow on the present. Klara Melkumyan moved with her family from Baku to this house on Firdusi street at the end of the 1980s, swapping her house with ethnic Azerbaijanis who lived in Yerevan back then.

Since the beginning of the Karabakh conflict in 1988 exchange of the housing became not only a short phase of a showcase of civic initiative but as any other form of forced resettlement, it has far-reaching and complex consequences. The story of village exchange[2] is an exemplary experience of an agreement reached by the civilian population, however exchange of individual houses of urban residents in many ways is different from that experience and has different premises and consequences.[3]

The residents of the periphery in many ways share a common way of life, everyday routine, and have a good idea of cultural, social, eco-climatic, and other conditions they will encounter after the resettlement. Exchanging the place of residence despite political and military decisions, they try to preserve the “natural” peaceful experience. [4] Living in the center of the capital, whether it is Yerevan or Baku, forms not only everyday life and cultural values that are different from others, but also more active participation in the current political discourse, and the process of integration in a new place implies getting used to the urban space, to the existing ways of social exchange and cultural landscape, and completely different ways of development of memory (family, local, language and others).

The exchange of housing between Armenians and Azerbaijanis in Yerevan and Baku is a story of separation with the places of compact settlement of these ethnic groups in the capitals of these former brotherly republics. One of them in Yerevan until the end of the 1980s was the Firdus quarter [5], located near the Republic Square (then Lenin Square) [6]. The quarter historically was populated predominantly by the Muslim part of the population (Azerbaijanis, Iranians) [7] of the Small City Center. Nearby there was a small mosque (next to modern-day Vernissage), which existed until the middle of the last century, as well as a modest cemetery, identify as “Tatar”[8] by the colonial cartographers.

Firdus suffered the last exodus of the Muslim population at the end of the 1980s when local Azerbaijanis were selling houses or swapping them with Armenians from Baku. [9] During past decades, as a result of the policy of gentrification, the vernacular quarter was partly demolished, and the remaining local population disagreeing with the new business decisions, continues to fight for their homes.[10]

One of the last resettles who disagree with these gentrification policies, is the family of Klara Melkumyan, who exchanged her apartment with Sofia Suleymanova. Neighbors on Firdus street often remember Suleymanova, and they well remember the day when Sofia left the house. “The entire neighborhood came out to see them off. Everyone was crying and hugging. Sofia kept it together until the end, but children were very worried,” recalls Klara’s neighbor Anahit Pkhrikyan, anticipating yet another separation from this place. “Probably, we will also have to load everything into the truck and leave this place in tears.”

From house to house/ From one house into another

Klara’s memories about her life in Baku resemble a big and colorful book woven together from a multitude of storylines that bring together social and political events of the past:

“I was born in Baku, not like others who moved from the villages. My umbilical cord was cut by Professor Ter-Mailyan, who was considered the best doctor in the country. I lived in the Bayil area, at 41 Khanlar street, but I spent my childhood on Bukhtinskaya street. My father worked in the oil fields. Back then valuable personnel were moved from Karabakh to Baku. He was born in 1910 in Martakert, [11] Nagorno-Karabakh. He moved to Baku, got married to my mother in 1935, and I was born in 1937. My mother is also from Karabakh.”

Klars’s childhood was split between Baku and Martakert. In her memories, the urban routine is mixed with summer months spent with her grandma Anna in Karabakh. The house in Martakert still exists, says Klara. For her, it is associated with the memories of maternal care, and at the same time, with the memories of losing her mother.

“My grandmother’s grave is there, and I can’t visit it.”

When Klara was three years old, her mother died while giving birth to her brother Volodya. She received maternal care from her grandmother with whom she spent all the years of war until her father returned from the front. Klara lived in her father’s house in Baku until getting married. Afterward, there were long years of waiting for new housing for her and her new family.

“My husband and I waited for twenty years to get a new apartment. At some point, I got desperate and wrote a letter to Mao Zedong for which I was called into the KGB. My husband was very scared for me, but I forbade him to come with me… I went alone to what was practically an interrogation, after which it became clear to me that we are not going to get an apartment anyway. Then, I decided that I have to make a trip to Moscow myself… I bought a huge bouquet of flowers, took my child, and flew to meet Tereshkova… I was received by her deputy and in a very respectful way, I explained to her that our family has been waiting to receive an apartment for many years now but Baku authorities keep denying our request. At that point, I already understood that it is not only a bureaucratic matter, but the delay is also caused by the fact that I am Armenian. I flatly refused to change my last name. After this trip, we finally were assigned a large multi-room apartment. After twenty years of waiting.”

Telling this story in June 2020, Klara glances at the clock as she is waiting for her lawyer who is helping her in the court proceedings on obtaining compensation for housing in Yerevan. After almost half a century, Klara has again to defend her right to a place of residence. The entire Firdus quarter, including Klara’s house, has been recognized as an area for “priority development.” The residents of the quarter are being evicted and are given monetary compensation based on the square meter of the lot and not the apartment. The government does not consider these houses as residential housing.

Returning to the memories of Baku past, Klara continues: “We just started to get comfortable in our new apartment, when we had to plunge into a new search. My husband went to the housing market every day, and I went to the post office looking through yellow pages for advertisements on the exchange “Yerevan for Baku, Baku for Yerevan.” Back then such advertisements appeared in the newspapers from time to time. We didn’t have Internet back then, unlike today. We would call and ask questions – what type of housing, where is it located, and then would go and take a look.”

In these memories of the search for a Yerevan apartment, aside from everything else, is the Melkyman family’s desire to live in the same conditions of urban space that are close and familiar to them. Klara has repeatedly rejected the offers to exchange her Baku apartment with one in the outskirt districts of Yerevan. Already back then, the house on Firdusi street looked poor and dilapidated to her, however, she chose this one because it was in the center of the city.

Klara’s recollections are her personal memory – a “way of processing the individual experience.” [12] Subjected to historical circumstance and political upheavals, this experience turns out to be a mirror gallery, mise-en-abyme,[13] revealing the general through private, personal, and intimate.

Eight decades of struggle with the state apparatus/machine and fight for a right to own home and own memories consist of unique blocks that are interconnected by the internal logic of a person’s desire to have his own place. Twelve years ago, city authorities recognized Firdus as a “territory for priority development” and began the process of land alienation. The quarters were physically destroyed, mercilessly breaking the established social and cultural ties of local residents. Including those, who many years ago were looking for new housing in the context of the tense situation around the Karabakh conflict, and like the Melkumyan family, trying to overcome the bureaucratic Soviet machine and proving their right to housing.

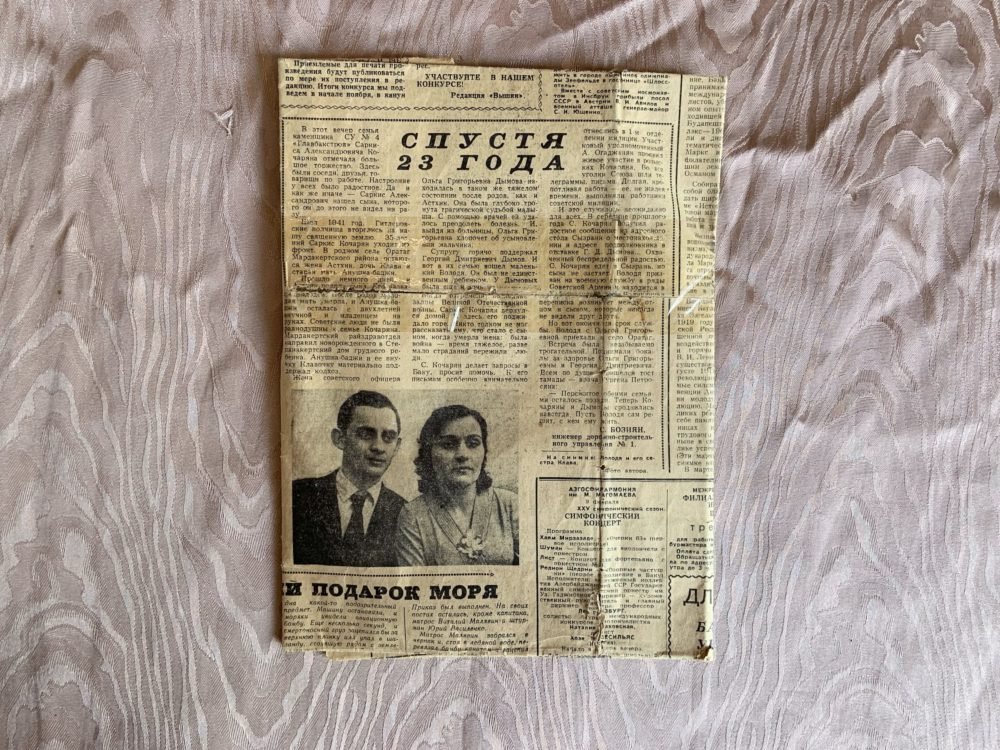

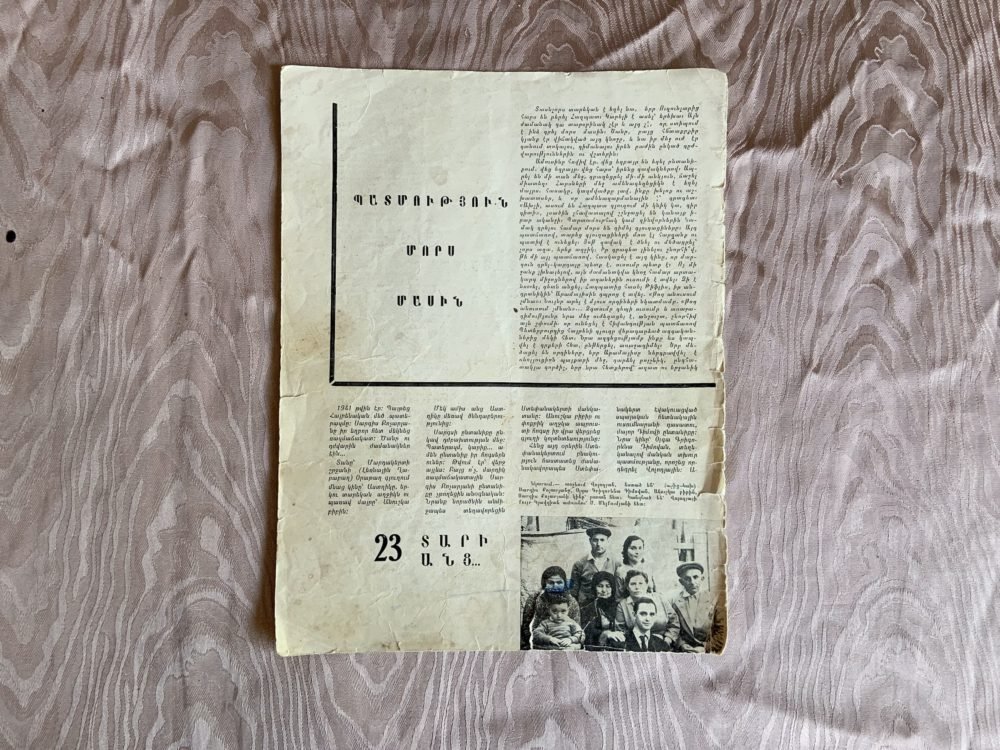

Strangely, this memory-experience chain often brings Klara back to the very roots. In the family photo album, two photos have a central place. On one of them it is young Klara dressed into a national dress of her grandmother Anna, and on the second one, a young lady with her brother Volodya forced separation with whom lasted quarter a century. On the eve of World War II, their mother died after Volodya’s birth, and a few years later, when their father was drafted to the front, the boy ended up in an orphanage, from where he was adopted by a Russian colonel from Syzran. A quarter of a century later, the family reunites – this story is told not only by Klara but also by Soviet newspapers of that time. Clippings of these articles are still kept in Klara’s personal archives.

Whatever Klara talks about, almost all her stories about the past begin with the memories of her brother, from whom she was separated by the war. This is a threshold point. Only after moving past it, Klara speaks about other events of the past, about other meetings and separations that she had to go through due to already another war at the end of the 1980s. This plot is important to her – from early childhood, she learns what separation is: from her family, from her hometown. Klara readily shares with her listeners stories about resettlement from Azerbaijan to Armenia, about current litigations with the developers, however, the story of unification with her brother takes up the biggest part of her memory stories. Perhaps, because it is the only major traumatic experience that had its happy ending. The rest continue to transform from one into another and drag on in a long series of nightmares.

“I used to work as a midwife and learned about what’s happening [the developments in Sumgait, resettlement of Azerbaijanis from Armenia] at work. Many were from the villages, called for or not, as soon as they found out that this is a new hospital, they came and started telling the stories. Back then I didn’t even know that there were so many Azerbaijani villages in Armenia. When they arrived [they constantly repeated] ‘we are from this village, we are from that village…'”

Recalling the work routine at Baku hospital, Klara always describes a friendly environment among the multinational hospital team. In these memories, the line of distinction often is not the ethnicity but the urban identity of the capital resident who faces the reality of the peripheries and people of different social status. In this context, it seemed that the patients who brought the news of the military situation were violating the “pact” of peaceful coexistence within the large female team of the hospital.

– “After the massacre in Sumgait, part of Sumgait Armenians moved to Baku, and our neighbors were telling us about that…. Another one came and told that Armenians were lying in piles by the sea…”

– … once, two ladies from a village come in [to the hospital] and start telling me how they fled from the Armenian villages, and how they were expelled from there. I forbade them to talk about it at the hospital and took them to the doctor. Back then the medical director of our hospital was Taira Ogaevna Alia-Zade…

She was a very fair woman. She urgently called everyone and said, “If anyone says a word about Armenians or a word about Sumgait….”

“Later Taira Ogaevna called me in and said, “Klara, what do you think about everything that’s going on?” I said, Taira Ogaevna, honestly, I haven’t changed my mind. I think we need to leave urgently. I was already in the process of exchanging apartments here. We already traveled once to look at the house on Firdusi.”

Memory of objects

The five-room apartment with a balcony will always remain one of the biggest losses of Klara’s Baku life. And not only because she had to leave her home with the beginning of the conflict, about which Klara talks with more confidence:

“We realized long ago that we have to leave. My son Artur from his childhood kept saying “Mom, Armenians need to live in Armenia. We are guests here. We are guests. We need to leave for Yerevan.” The apartment left in Baku is a lost symbol of her personal victory over the Soviet bureaucratic machine, victory over the national discrimination that she suffered from officials and bureaucrats. Perhaps that’s why showing the rooms of her house, Klara demonstrates with pride items that she was able to move with her – fragments of this victory, fragments of the place of residence conquered from the Soviet state.

From the things she brought with her, Klara, first of all, shows the jubilee issue of the newspaper “Communist” on one of the pages of which there is a photograph from the opening of the Narimanov metro station in Baku and young Klara Kocharyan among the passengers. The jubilee issue of “Communist”, which was published in Baku in Armenian, [14] is a kind of personal memorial about a place that is accessible today only in memories.

On the living room wall, there is a chased work of art – a man defeats a sneak.

“As far as I remember, this is a symbol of their city, and I brought it with me,” tells Klara. Another relic brought from Azerbaijan is a metal bed that is in one of the back rooms of the house. The bed stands in an almost empty room, which the Melkumyan family rented out to students or Iranian traders from time to time. Today, when the issue of demolition of the quarter and the house looms, and the market activity has died down, the room stands empty and the bed is locked in this emptiness, as if in a secret room of a museum of personal memory.

“My husband brought a big truck and we started loading all our belongings onto it. When we moved everything out, I said that we need to also take the door. Here, it is now in my kitchen. Klara’s memory museum opens with an object from the past, a door, that she didn’t want to shut behind her when leaving Baku.

The memory of the place

If items and photographic archives remind of the lost home in Baku, then the walls of the house talk about those who left Yerevan. Klara shows small square notches in the wall explaining that these were sort of storage units and refrigeration places. Then she goes down to the basement where the arches, vaults and small holes that once served as windows speak of the ascetic and poverty of the Suleymanov family and that they spent most of their life in this space. While showing the basement, Klara tells how during the first years of living on Firdusi, her husband constantly was doing home improvement projects. Above the brick basement level, there is a wooden ceiling. “I met the landlady Sofia here, but her sons were studying there with us, there were good boys. When they were living there, her sons were crying, they didn’t want to leave this place.”

For many years now, above the sideboard that was moved from Khanlar street to Firdusi street, hangs the portrait of Klara’s late husband. It was with his hands that the Suleimanovs’ house was being completed during the difficult period in the 1990s. One of the consequences of the crisis in Armenia during these years was the massive labor migration to Russia. Klara’s sons were also among the labor migrants.

Today Melkumyan continues to live on Firdusi alone, surrounded by items that are an inseparable part of her museum of memories. Together with the squeak of the wooden floor, these objects remind of other residents who used to live at the basement level. The bricks of the basement have grown roots into the soil, the same way as the entire Firdusi quarter has grown roots into the flesh of Yerevan and became an intimate memorial of fading family memory.

Over the precipice of oblivion

After the alienation of the quarter and the start of the construction, Klara’s house has literally been hanging over the cliff for several years now. The foundation pit for a new residential building was dug behind the house. Klara continues to sue the new developers, who try to evict her by paying minimal compensation.

The palimpsest of traumatic memories reveals one layer after another, painting Klara’s story: from the Martakert house to the expectations of a new apartment in Baku and compensation from a housing complex in Yerevan, formerly known as Glendale Hills and mired in corruption schemes. Firdus residents do not want to leave their houses for various reasons: if Klara is careful with developers since she remembers well how she lost her large Baku apartment, then many other residents do not want to get used to the fact that houses built by the hands of their ancestors, refugees from Van, Mush, Erzrum, and others suddenly became a “priority development zone” and from now on no longer belong to them. Firdus has many stories to tell about migration, about the memory of those who left the quarter, about those who were welcomed here after the disaster, and helped to build a new home throughout the 20th century. This palimpsest of memories about migration, catastrophes, personal, intimate, and private, that is inevitably intertwined with a big history, today is threatened with the total disappearance.

Developers and contractors in their high-level offices are rewriting the history of the city with a simple graceful pen stroke, destroying the memory of a peaceful neighborhood and human community, forcing people to leave their homes again.

The material uses illustrations by Harutyun Tumagyan, photographs by Clim Grechka, Lala Aliyeva, Lilit Gizhlaryan, and Tigran Amiryan, photographs from the personal archive of Klara Melkumyan.

References

1] The term gentrification is used to describe a process of reconstruction and revival of those urban areas that have fallen into decay over time or did not develop properly. However, in the case of Yerevan, for two decades now under the pretext of improvement or reconstruction almost all historical quarters of the city have been destroyed. Behind a tarpaulin fence with the inscription “More comfortable Yerevan,” in particular during the presidency of R. Kocharyan, residential and administrative buildings and entire quarters of the historical center were destroyed.

2] Huseynova S., Hakobyan А., Rumyantsev S. Beyond the Karabakh Conflict: The Story of Village Exchange. Heinrich Boell Foundation South Caucasus Regional Office, 2012.

3] See, for example, Experiencing Displacement and Gendered Exclusion: Refugees and Displaced Persons in Post-socialist Armenia and Azerbaijan

4] On the consequences of the migration process of Armenians and Azerbaijanis and various factors of later psycho-geographic integration of urban and rural residents see the works of Evin Hovhannisyan. For example, see E.H. “Exorcism of Cultural Otherness”: The Refugee Women in Post-Soviet Armenia. in Security, Society and the State in the Caucasus, 2018, Routledge.

5] I write in more detail about this in the book Firdus: the memory of a place. Collective monograph ed. by T. Amiryan, S. Kalantaryan. CSN lab, Yerevan, 2019.

6] The Muslim population of Firdus has a long history of migration. The first serious trauma to the local multicultural quarter was caused during the Stalin era, when by the decree of Soviet authorities, from the late 1940s to the early 1950s, part of the Azerbaijani population was resettled in the valley of Kura and Arax rivers to free up living space for Armenians repatriated from the Middle East and Europe. However, these repatriates also did not live here long, as they were deported to Siberia soon.

7] Lilit Gizhlaryan, The Muslim Heritage of Yerevan: Not Just Another Brick in the Wall

8] It should be noted that under “Tatar” Russian-language maps and other documents mean “Muslim”, but it is obvious that this is not about the ethnic group of the Tatar population, but about places of compact residence of the non-Christian, Muslim population, most of whom were Azerbaijanis. In addition, on Hanrapetutyan street (formerly Lenin Street) in the northern part of the quarter, a representative façade of the building that served as the residence of the Persian consul in the 19th century is well preserved.

9] I present more details on the neighborhood and cohabitation of Armenians and Azerbaijanis in the quarter here http://boon.am/firdous/

10] It should be noted that Firdus is a quarter where a dense network of migration memory has been forming for many decades now. After 1915, refugees from the Ottoman Empire began to settle here and a part of the quarter is occupied by Armenian settlers from various regions of Armenia. After the Karabakh conflict, as a result of the exchange, settlers from Azerbaijan begin to live here, and since the 1990s, when Firdaus turned into a street market, we can observe cohabitation of Armenians and Iranians.

11] Azerbaijani name of Martakert is Agdere/ az. Ağdərə.

12] Assaman A. A long shadow of the past: Memorial Culture and history politics; Translated from German by B. Khlebnikova. – Moscow: New Literary Review, 2014, p.21 (In Russian).

13] The literary term, translated from French, meaning “immersed in the abyss,” is used in the meaning of “story within a story,” a narrative built on the principle of matryoshka/nested dolls.

14] The newspaper “Communist” was being published in Baku since the 1920s. The main language of publication was always Armenian. “Communist” stopped being printed with the start of the Karabakh conflict at the end of the 1980s.