In Between Politics and Borders

The Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazian, and South Ossetian conflicts, that emerged at the collapse of the Soviet Union, all resulted in a massive displacement of civilians. Some of them left the South Caucasus altogether. Others integrated into the other societies of the region. Yet, hundreds of thousands of the displaced are still residing in temporary shelters in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, as well as in the breakaway territories of Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno-Karabakh. The conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, that came at the turn of the 21st century, in turn resulted in the inflow of refugees to the South Caucasus, compounding the problem and overwhelming the shelters. According to the official sources, today there are about 1 million 200 thousand refugees, internally displaced persons, and asylum-seekers residing in Azerbaijan (a number that includes the displaced as well as their descendants[1]), 229,089 displaced persons in Georgia[2]. Demographic data regarding displaced persons in Armenia is not readily available and accurate. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, around 420,000 displaced persons came to Armenia[3]. Among them, 360,000 people were displaced from Azerbaijan because of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The socio-economic hardships of the later years caused a large part of the displaced to leave Armenia․The overwhelming majority of the remaining people have been granted citizenship and no longer hold the status of refugees. As of June 2017, UNHCR Armenia reports that there are a total of 18,606 people of concern – refugees, asylum-seekers, persons in a refugee-like situation – in Armenia. These include mostly persons displaced from Syria, Iraq, Ukraine, Iran, and as a result of the April 2016 escalation in the region of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict[4].

Some of the displaced have made a fresh start in their new places of residence and are well-integrated, but tens if not hundreds of thousands of others live in impoverished conditions, often for more than a quarter of a century, and with no visible prospect of return or integration.

In addition to the social problems, their status is also politicized and contested. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, also known as the UN Refugee Agency differentiates between a Refugee and an Internally Displaced Person[5]: “A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence”, while “an internally displaced person (IDP) is a person who has been forced to flee his or her home for the same reason as a refugee, but remains in his or her own country and has not crossed an international border. Unlike refugees, IDPs are not protected by international law or eligible to receive many types of aid”. In other words, a refugee is displaced from another country, while an IDP is displaced within their own country. And as the borders in the South Caucasus are contested, so is the status of these already disadvantaged populations. Azerbaijan and Georgia rely on internationally recognized boundaries and identify Azerbaijanis displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh and Georgians displaced from Abkhazia and South Ossetia as IDPs. At the same time Armenia, and the authorities of Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia, breakaway regions that consider themselves independent, identify most of the displaced in the South Caucasus as refugees.

The status, in turn, might determine the social standing of the individual, the welfare benefits they are or are not entitled to. With politics dominating, the very real everyday life, struggles, and joy of individuals are pushed to the background.

In the story that we present to you, our intention is to step away from definitions, numbers, and statistics, instead giving the stage to the real people affected by the conflicts in the South Caucasus and its neighborhood. The videos that follow are filmed in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia, presenting the voices of eight people, with their struggles and their success; eight people stranded in between politics and borders.

Footnotes

[1] n.d. “The Social Development Fund of Internally Displaced Persons of the Republic of Azerbaijan.” (Azərbaycan Respublikasının Məcburi Köçkünlərin Sosial İnkişaf Fondu). Accessed November 9, 2017. http://sfdi.gov.az/?options=content&id=37.

[2] n.d. “Social Service Agency of Georgia.” (სოციალური მომსახურების სააგენტო). Accessed November 9, 2017. http://ssa.gov.ge/index.php?lang_id=&sec_id=1247.

[3] State Migration Service of the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Development of the Republic of Armenia. 2010. “Policy Concept on the State Regulation of Migration of the Republic of Armenia.” (Հայաստանի Հանրապետության Միգրացիայի Պետական Կարգավորման Քաղաքականության Հայեցակարգ). Accessed January 17, 2018. http://www.smsmta.am/?id=948.

[4] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2017. United Nations Armenia. Accessed January 17, 2018. http://www.un.am/en/agency/UNHCR.

[5] n.d. “What is a Refugee?” Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Accessed November 9, 2017. http://www.unrefugees.org/what-is-a-refugee/.

* This publication has been produced with support from the US Embassies in the South Caucasus. The opinions expressed in the publication reflect the point of the view of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the US Embassies.

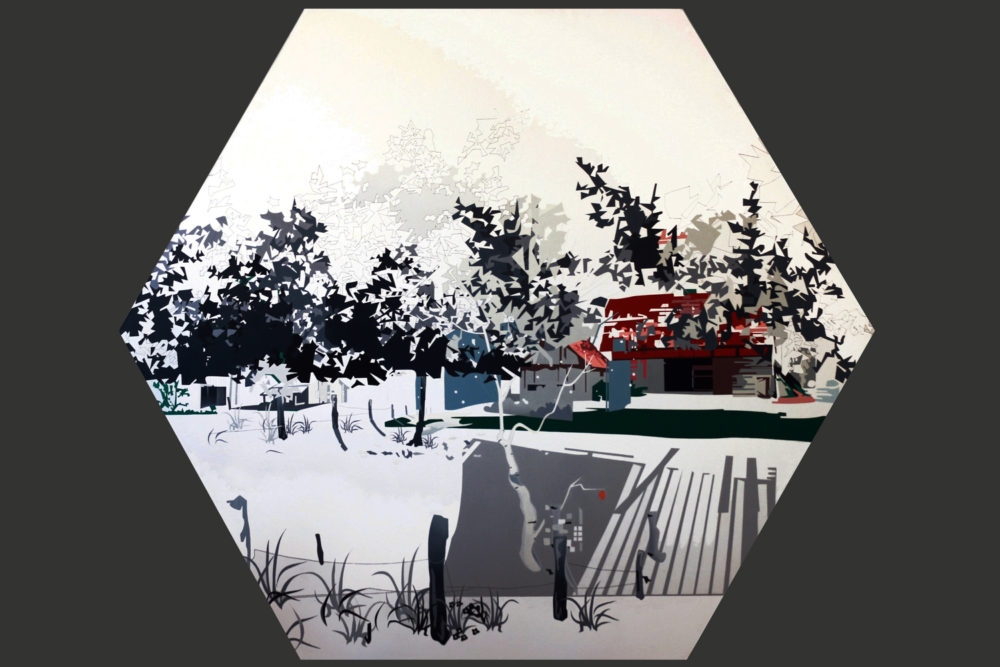

** The cover photo of this piece is a painting by David Kareyan titled “My Heart is Your Home”. Permission has been obtained for using the photo.