What can a person or a group do if they are deprived of voice and the freedom of expression? When they cannot speak up about their problems and raise issues they are concerned about in the public space? When they do not have access to mainstream media to reach wider audiences? When they are oppressed in one way or another or struggle for survival? In other words, how can people cope with structural violence – the systematic harm that can be done through certain social structures and institutions?

For the last few decades, street art has increasingly become a powerful tool for the voice of the oppressed in different parts of the world. People from minority groups, the underprivileged, the marginalized, civic and human rights activists often use it as a means of communication. They create influential images and messages illustrating their concerns and troubles. They trigger discussion about underrepresented or tabooed topics. Often anonymous, street art challenges the dominating public opinion, questioning issues of justice, security, roles in the society, raising the voices of those who are excluded from political decision making and the public space.

Publicity and easy access are both a strength and a weakness for street art. Images or messages are usually placed where people can notice them. For the same reason, they are easily spotted and erased by those who oppose the image or the message. Some of them can “live” for a few hours; others “resist” a few days or weeks. Rarely can street art survive for a few months, especially if it represents “unpopular” views. It is impossible to predict the exact “life cycle” of street art. It is frequently erased, broken, deleted, painted over, and dissolved.

For the past decade, the South Caucasus societies have also seen a surge of street art-ctivism. Groups and individuals have used it as an alternative way of public speaking. They have raised and protested issues ranging from unfair socio-political processes to specific cases of oppression, injustice, and violence.

In this piece, we present selected works of street art – street artwork – in Armenia and Georgia. Most of them do not exist anymore. They have been subject to official or unofficial “censorship” and “cleaning”. The photographs were taken in different cities of Georgia and Armenia and depict deeply embedded issues in these societies. Some of these pieces have common topics and address the same issues in both societies. Others are related to country-specific issues. These artworks belong to brave art-ctivists who deliver “unsanctioned” images and messages to the public space, raise the silenced voices in their societies, and strive for changes in their communities. They “speak” about people’s feelings and attitudes and can, therefore, contain commonly used language, including swear words and other kinds of expressive language.

This 2015 piece of street art in Yerevan tells you that street art-ctivism is “A Method to Struggle”. The artist’s pseudonym is Hakaharvats meaning “counterblast”.

Common Topics in Georgian and Armenian Street Art

Against Political Oppression, Regimes, and Surveillance

George Orwell’s famous dystopian book “1984” describes a system where everyone is under the strict control and surveillance of the state. “Thinkpol” – the Thought Police – identifies and punishes Thought Criminals – those who have the capacity of independent thought. There is no space for real freedom in Oceania. Screens and informers are everywhere. Thinkpol immediately eradicates any alternative to the official version of reality. Only one political party is entitled to set rules, take office, and make political decisions. There is no real freedom of choice, democracy, and public will in Oceania.

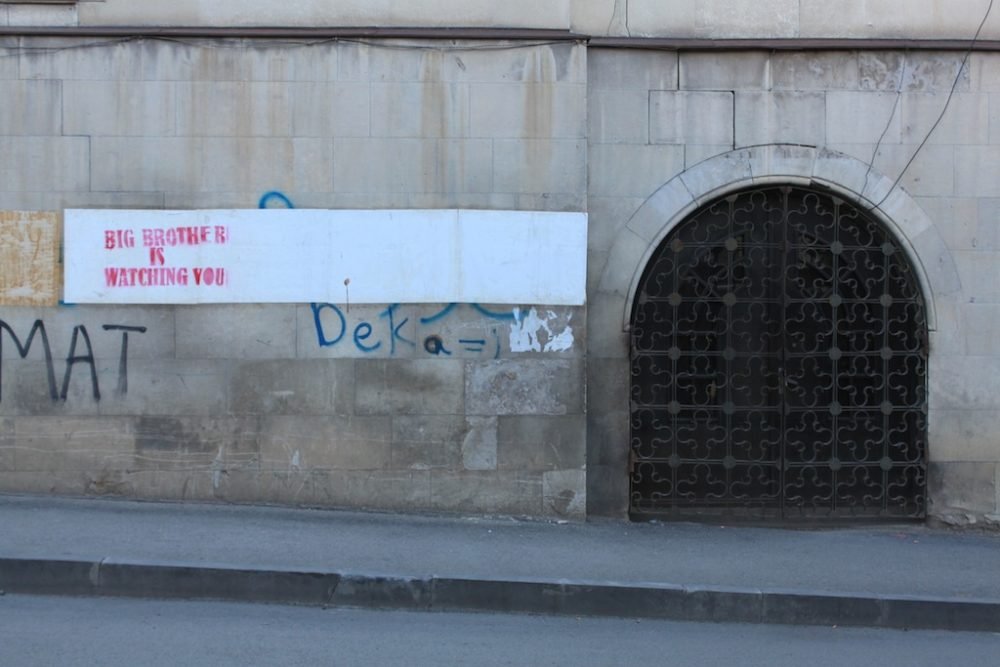

A similar interpretation of reality inspired an unknown street artist in Georgia to make a number of drawings. The first photo was taken on May 18, 2012 in Tbilisi. It was during the then President Mikheil Saakashvili’s second term in office. It has been widely believed that back then the government systematically violated the citizens’ privacy. Secret phone surveillance was so prevalent that nobody felt safe. The obtained materials were used for blackmail and political repression. Distrust and fear were rooted in all the layers of the political and social structure. “Big Brother is Watching You” was written onto walls in central Tbilisi, among them the wall of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia and the underground passage of Liberty Square.

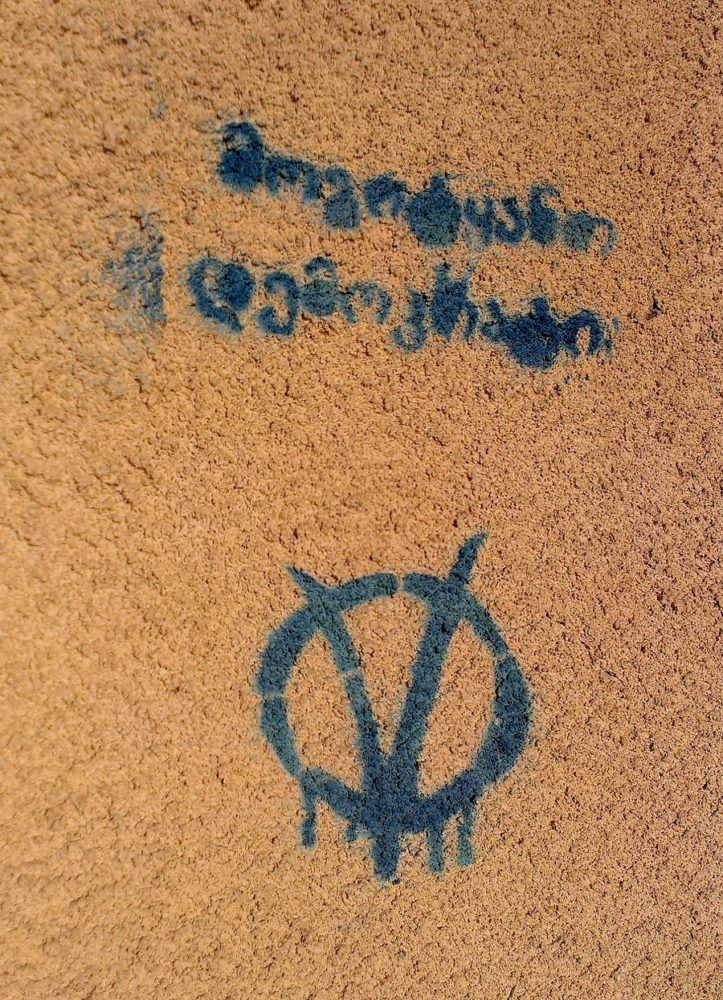

The below image that can be interpreted to have a similar message appeared in Yerevan. It seems to illustrate the sense of control and surveillance prevalent in the society.

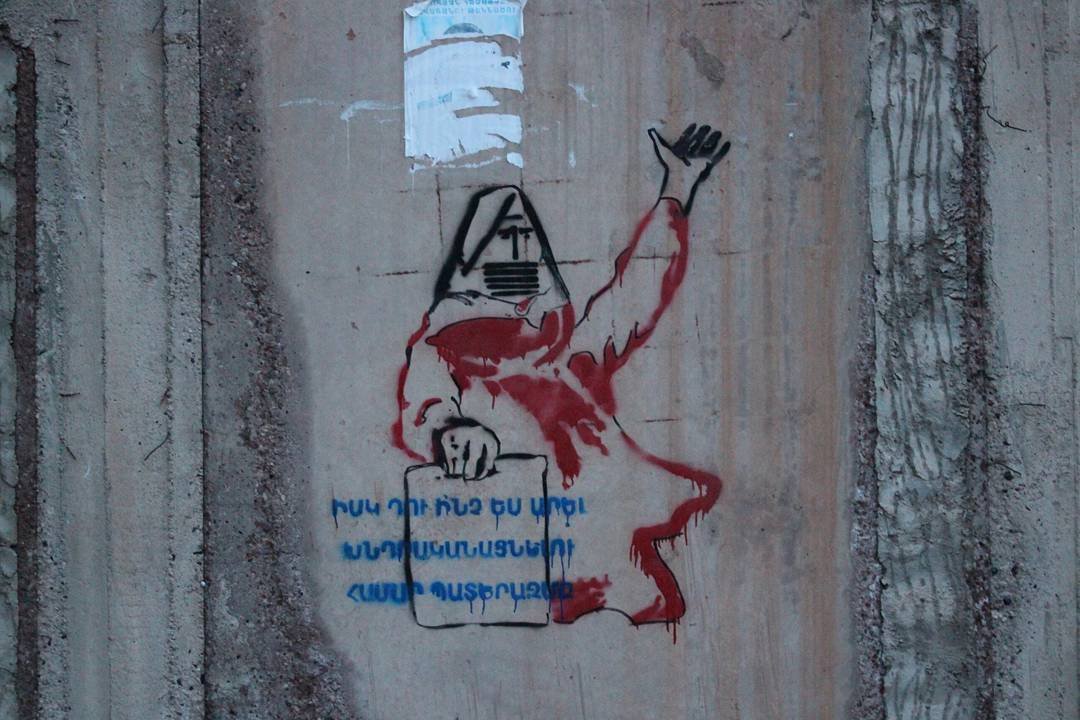

And below is another one from Rustavi, Georgia, illustrating resistance to a democracy that does not work well.

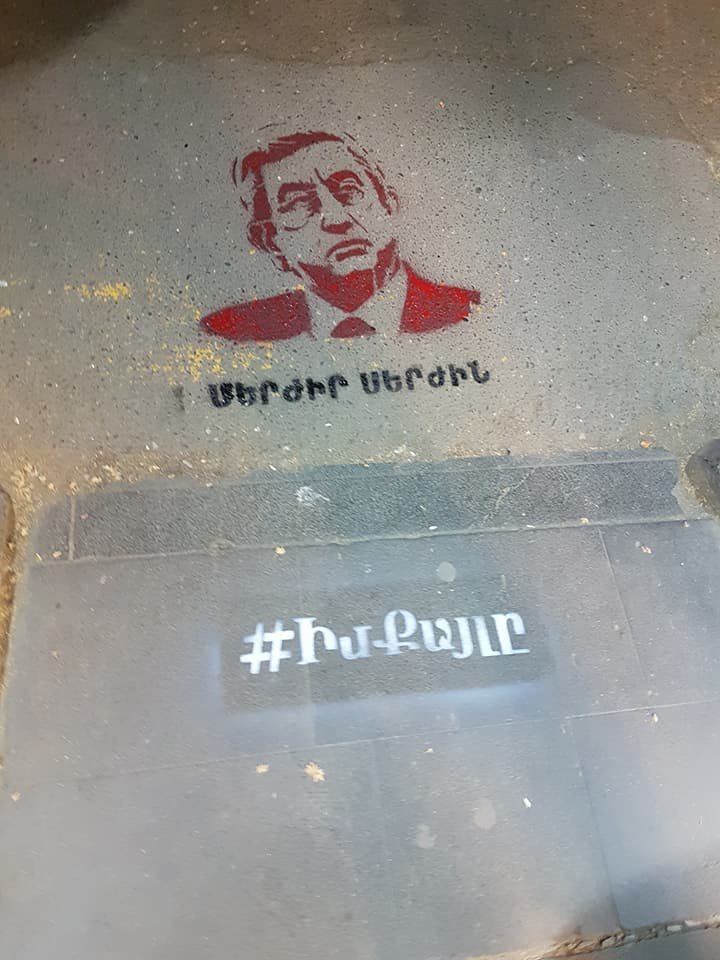

In March 2018, two initiatives “My Step” and “Reject Serzh” started a movement to prevent the appointment of the former Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan in the post of the Prime Minister of the country. As a result of the “Velvet Revolution”, Serzh Sargsyan left the post of the Prime Minister where he had stayed only a few days. The opposition Member of Parliament and the leader of the protests Nikol Pashinyan became the new Prime Minister of the country. The struggle of the people against the corrupted authorities and the ruling Republican party took roughly 40 days of street protests. Throughout this period, dozens of new pieces of graffiti appeared in the streets of Yerevan calling people to take their own step and join the movement.

Confronting Gender- and Sex-Based Violence

Many pieces of street art challenge the dominant perceptions about gender and sex. They question the traditionally assigned gender roles and emphasize the need for changes.

The artwork below was photographed in the underground passage at Liberty Square in Tbilisi on September 23, 2011. It is a collage of two famous female-icons. The head of the figure “belongs” to the Statue of Liberty in New York, USA. The body is a modification of the Mother of Georgia statue in Tbilisi. It still holds a bowl of wine intended “for friends” and a sword intended “for enemies”. However, unlike the original one, her dress is short, and she is wearing high heels. This way the unknown artist illustrates the transformations of the traditional role of women.

In 2013, UNDP Georgia conducted a research on the “Public Perceptions on Gender Equality in Politics and Business” (UNDP Georgia 2013). Based on the findings, they organized a campaign in Spring 2014. As part of the campaign, the images of the most popular gender stereotypes that hinder the advancement of women were painted on the pedestrian sidewalks in the streets of Tbilisi. Afterwards the images were crossed out by red paint, and the message “Destroy the stereotype” was added below. In March 2014, at the end of the campaign, UNDP Georgia arranged a public discussion, accompanied with a performance. It was called “Gender Stereotypes That Can Be Destroyed by Paintball Bullets”.

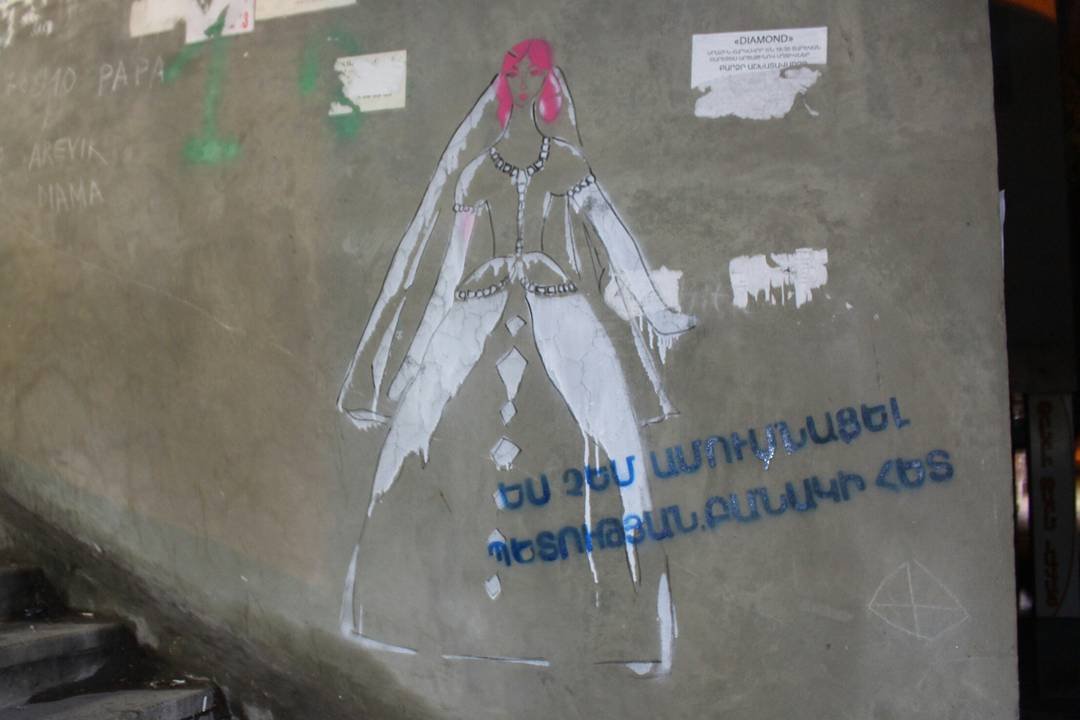

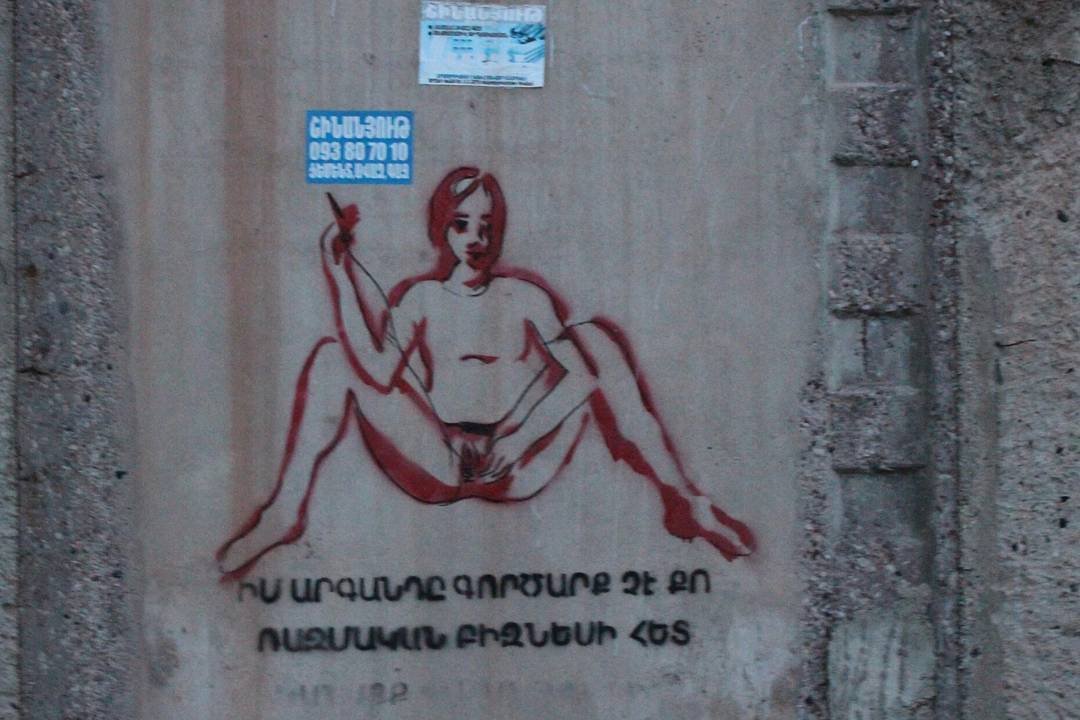

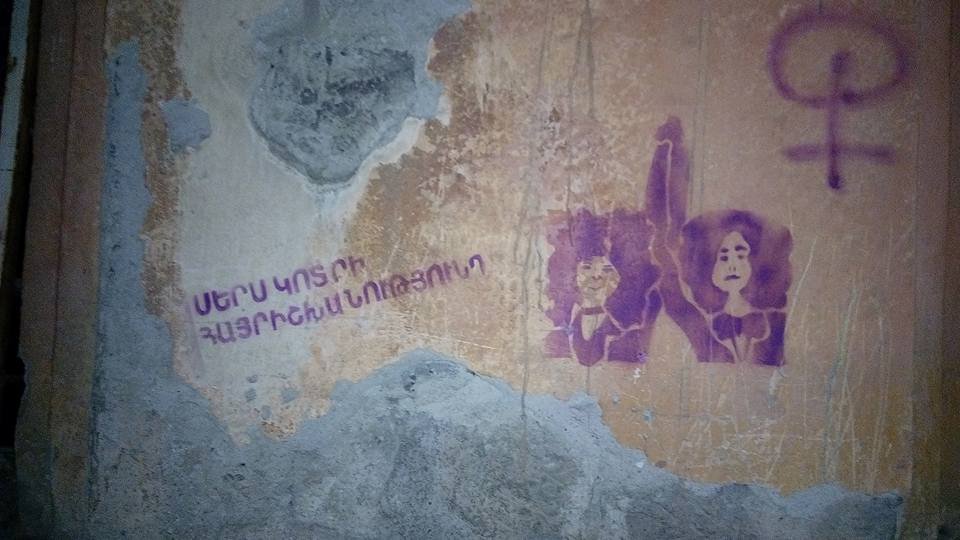

In Armenia, gender- and sex-related street paintings appear both in Yerevan and in the other cities.

Arpi Balyan is an artist based in Abovyan, Armenia. Her messages are mostly focused on anti-militarization, the war-business, and feminism. She also considers herself a feminist. In the artwork below, she depicts a woman with the writing, “And what have you done to problematize the war?” The image of the woman is a collage of various female-icons. The head is part of the monument “We are our Mountains” (also known as “Tatik-Papik” meaning “Grandfather-Grandmother”) that is considered a symbol of Nagorno-Karabakh among Armenians. The body “belongs” to the well-known Soviet poster “Rodina-Mat’ Zovyot”[1] meaning “The Motherland Calls”, used for mobilization during the Great Patriotic War[2] .

Arpi is not the only artist who expresses direct protest against the existing order of the society. Others also challenge the male-dominated and masculinist culture and norms.

A banner against sexual violence in conflict was placed onto the wall of the British Embassy in Yerevan, next to the residence of the President (now residence of the Prime Minister) of the Republic of Armenia.

The painting below exposes the structures that oppress women and their struggle for their rights – the police and the court system. It depicts a woman who is trying to speak out but two hands – one labeled as belonging to a judge and the other to a policeman – cover her mouth to force her to stay silent.

Medialab made the painting in October 2017 to draw the attention of the Armenian society to domestic violence. According to the Human Rights Watch, “Armenia’s Coalition to Stop Violence Against Women, an alliance of nongovernmental women’s rights organizations, reported that at least four women were killed by their partners or other family members in the first half of 2017, and at least 50 were killed between 2010 and 2017. The Coalition received 5,299 calls about incidents of domestic violence from January through September 2017” (Human Rights Watch 2018).

The painting was made as part of the campaign that supported the adoption of the law on domestic violence (Stepanian and Aslanian 2017). The law was passed in December 2017 with great difficulty, and it caused heated debates in the society. Some parts of the society perceived it as a threat to the traditional family and values. They also have argued that the police and the state should not have the legal right to interfere in family matters.

This next piece is a parody of a popular TV commercial in Armenia from several years ago. In the commercial, two women, Parandzem and Taguhi, are cooking. Taguhi, who chooses to cook the meal with the advertised grains, is able to finish earlier and leave for the dance club. Meanwhile, Parandzem has to keep on cooking the entire night since she chooses the “ordinary” brand of grains.

Women’s rights supporters considered the advertisement sexist and assigning women the role of the cook in the family. Since there is little space to contest this role on the same media platforms that would air such a commercial, street art is the alternative space to challenge the engrained perceptions of women’s roles and needs.

The below photo was taken in January 2018. The stenciled phrase is located on Parpetsi Street where the only LGBTI bar in Yerevan used to operate. The exact date the phrase appeared on the wall is unknown, but we can assume that it was made after 2012, when the bar closed after an arson attack, and the owner of the pub had to leave Armenia.

The below graffiti directly challenges the traditional viewpoints on love, relationships, and hierarchical, male-dominated structures of the society. It has two women with the phrase, “My love shall break your patriarchy”.

Against State Violence, Lack of Justice, and Police Violence

On May 31, 2018, the Tbilisi City Court announced a decision on the so-called “Case of the Khorava Street”. On December 1, 2017, in broad daylight and in front of many witnesses, a group of teenage boys brutally killed two 16-year-old schoolmates – David Saralidze and Levan Dadunashvili. Multiple wounds inflicted by knives caused their deaths. Based on the evidence presented by the investigation, the court found guilty one person in the death of Levan Dadunashvili and another one in the “attempted murder” of David Saralidze. The father of the victim Zaza Saralidze asked people for support to achieve justice for his son and punishment of his killers. He believed the prosecution covered up the criminals and did not investigate the case properly, due to their connections with high-ranking law-enforcement officials.

Thousands of people gathered on Rustaveli Avenue, Tbilisi to express support to Saralidze. They required justice and the resignation of the high-ranking governmental figures. On May 31, 2018 the Prosecutor General of Georgia resigned. The mass protest lasted for several days. The Prime Minister, the President, and the Public Defender of Georgia and other officials met Saralidze and promised fair investigation of his son’s case. Civil society representatives, writers, and other groups also empathized with him. The Parliament formed a Temporary Investigative Commission to study the “Case of the Khorava Street”. As a result of mass protest, the Ministry of Internal Affairs started the re-investigation of the case.

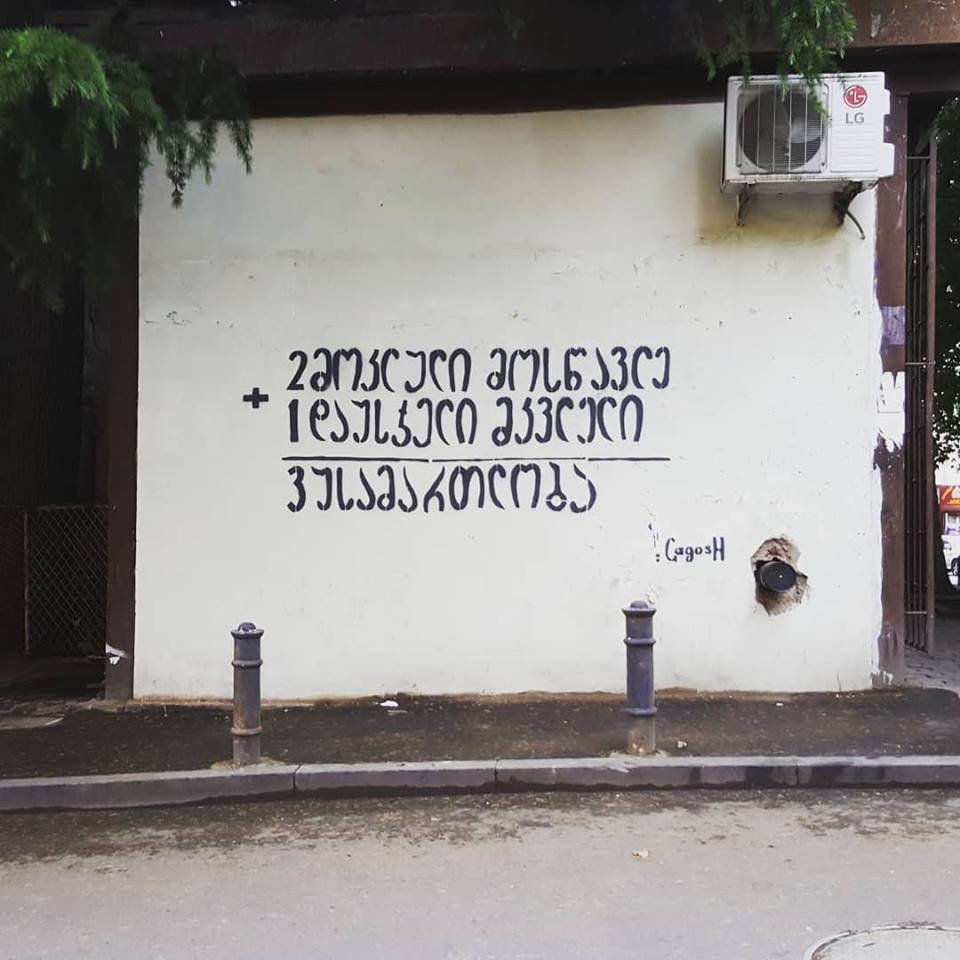

These developments inspired two artists to create new artwork. They reflect the struggle for justice that grew from personal grief to public support and wider socio-political outcomes. On June 2, 2018 Gagosh published a new photo on his Instagram page: “2 murdered pupils + 1 unpunished murderer = 3 injustices”. The caption at the photo says, “Arithmetic actions always lead to indisputable truth. Today the Prosecutor’s Office and the Government are standing at the blackboard and cannot solve the simplest equation…”.

Another artwork appeared two days later and almost immediately became subject to alteration. It was made on June 4, and the next day someone “corrected” it, erasing the writings.

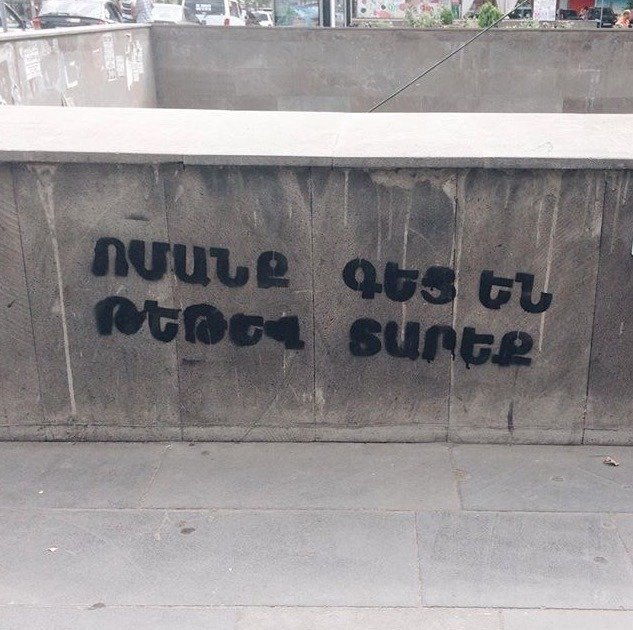

On August 7, 2017, 22-year old Demur Sturua committed suicide in the village of Dapnari, Samtredia Municipality, Georgia. In his farewell letter, he accused a police officer in persecuting him and threatening his life. He wrote that the officer was forcing him to share information about people who cultivated cannabis. The stenciled art with an excerpt from his letter appeared in several locations in Georgia, among them Kutaisi, Zugdidi, and Tbilisi.

The words “Mom, you are left alone, but I have no other way” have become the voice of those who have been under the pressure of the police and other state structures, especially those who have been victims of the very strict anti-drug policy.

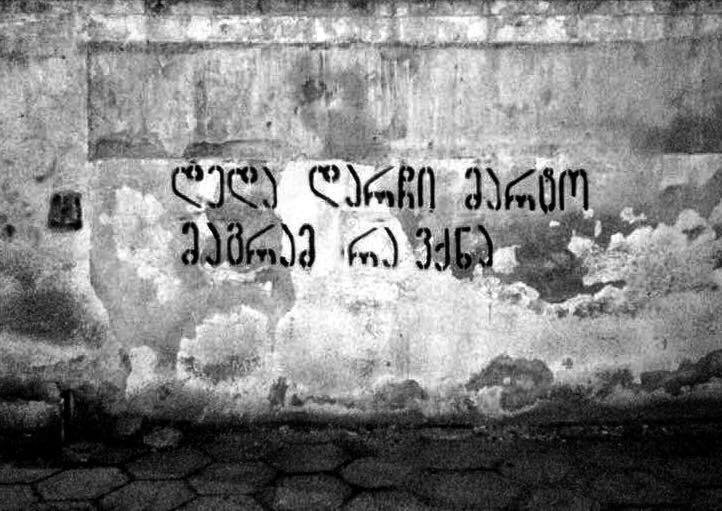

On December 24, 2017, the Georgian poet Zviad Ratiani was beaten in the street and arrested by police officers. Insults and resistance to the police were named as the official reasons for the arrest. Meanwhile, the poet stated that the incident started because the officers did not like his colorful jacket. This inspired Gagosh (it is the pseudonym of a Tbilisi-based street artist, who creates stencils, installations, street poetry, and mosaics) for the new artwork in the center of the city.

In July 2016, an armed group called “Sasna Tsrer” (meaning “Daredevils of Sasoun” and borrowed from the title of the Armenian epic poem) captured a police station in Yerevan and took hostages. The demands of the attackers included the release of one of the opposition leaders Jirair Sefilian from prison and the resignation of the then President Serzh Sargsyan. The police surrounded the station, and the siege lasted nine days, leaving those inside without food. A man named Artur Sargsyan drove through the police barricades delivering bread and food to those inside the police station. He was arrested as a “supporter of terrorists” and died in prison as his health issues were complicated by a hunger strike (Arka.am 2017). Many in Armenia consider him a role model of humanism. The below painting was made on the wall of the Parliament of Armenia.

The piece below represents a Santa Claus as he is being arrested by a policeman. The painting refers to incidents in Yerevan around New Year 2016. In December 2015, an opposition movement called “New Armenia Public Salvation Front” protesting on Freedom Square tried to have an “alternative celebration” of the new year with the attributes of Grandpa Winter, Snow Maiden, and a new year’s tree. The attempt was blocked by the police. On January 1, the member of the movement Gevorg Safaryan dressed as a new year tree tried to join the others on Freedom Square. He was arrested and later sentenced to two years for “use of force against the police” (Human Rights Watch 2016). Many in the civil society in Armenia consider him a political prisoner. He was released from detention most recently.

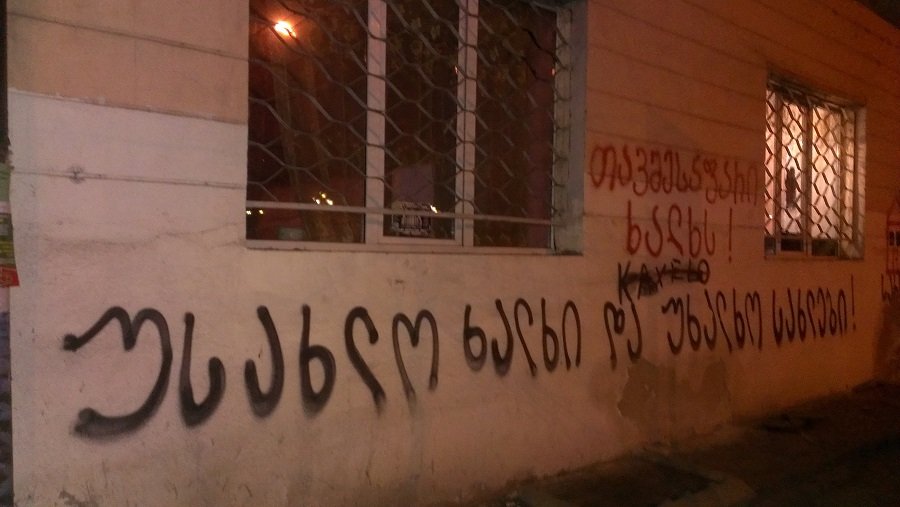

Opposing Social Injustice and Poverty

These two small artworks at the entrance of the British Council were photographed in September 2012 on Rustaveli Street in Tbilisi. They depict the devastating poverty that some people live in. One of the figures has a loaf of bread instead of a head and the other one has a house. Respectively, the writings above them say, “I am hungry” and “I want a house”.

This next writing on a wall on Atoneli Street in Tbilisi emphasizes a tragic reality – thousands of people have lost their houses because of debts.

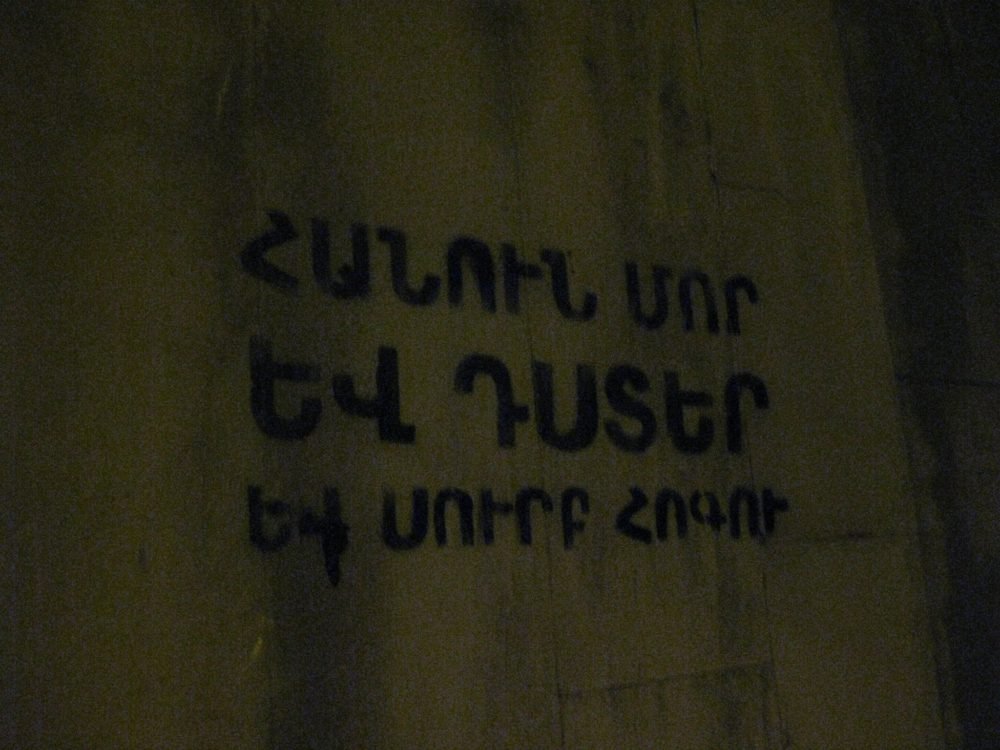

The following stenciled phrase also emphasizes social inequality in Armenia.

Footnotes

[1] The original poster can be viewed here: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Файл:Ussr0437.jpg.

[2] The term “Great Patriotic War” is used in some of the former Soviet Union countries to describe the conflict fought within the Second World War from June 22, 1941 to May 9, 1945 between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany and its allies.

Bibliography

Arka.am. 2017. Bread Bringer Dead, Things Growing Tense in Yerevan. March 17. Accessed March 6, 2018. http://arka.am/en/news/politics/bread_bringer_dead_things_growing_tense_in_yerevan/.

Human Rights Watch. 2018. Armenia: Little Protection, Aid for Domestic Violence Survivors. January 12. Accessed March 6, 2018 https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/01/12/armenia-little-protection-aid-domestic-violence-survivors.

—. 2016. Armenia: Opposition Activist Jailed. January 8. Accessed March 6, 2018. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/08/armenia-opposition-activist-jailed.

Stepanian, Ruznna, and Karlen Aslanian. 2017. “Armenian Parliament Passes Bill Against Domestic Violence” Azatutyun.am. December 8. Accessed march 8, 2018 https://www.azatutyun.am/a/28905131.html.

UNDP Georgia. 2013. Public Perception on Gender Equality in Politics and Business. November 25. Accessed March 6, 2018. http://www.ge.undp.org/content/georgia/en/home/library/democratic_governance/public-perceptions-on-gender-equality-in-politics-and-business/.

* This story has been produced with support from the US Embassies in the South Caucasus. The opinions expressed in the publication reflect the point of the view of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the US Embassies.

** Read Part 2 of this Story here.