The territorial making of modern Armenia and Azerbaijan was the first task facing the Bolsheviks a hundred years ago. The difficulty of border-making was acutely felt in Zangezur, Nakhchivan, and the mountainous parts of Karabakh. An arbitrary decision was made to quell the Armenian-Azerbaijani dispute, though the Bolshevik territorial arrangements left many dissatisfied. After all, it was practically impossible to create two distinct, territorially-defined national spaces encompassing all regions inhabited by Armenians and Azerbaijanis. This difficulty arose largely because in most cases these two communities coexisted, making clear-cut territorial divisions problematic.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, which had once arbitrated borders, presented an “opportunity” to re-negotiate the dissatisfaction accumulated over seven decades. Unfortunately, what could have been resolved through peaceful means—though such historical examples of such resolution are scarce—escalated into one of the most violent conflicts of the modern era; over a million Armenians and Azerbaijanis were displaced, leaving numerous towns and villages in ruins.

The outcomes of the First Karabakh War placed Armenia in a situation that diverged significantly from its international representation on the map. The reality on the ground was that of an “augmented Armenia” stretching from Gyumri to Fuzuli. On the other hand, for Azerbaijan restoration of territorial integrity became an identity marker. Even ethno-cultural connections with Azerbaijanis extending beyond the borders of Azerbaijan were sometimes rejected, fearing that this might undermine the “cause.”

The Second Karabakh War and, most recently, the “One Day War” in 2023 have brought about unprecedented shifts. To a large extent roles have reversed; preserving Armenia’s territorial integrity has emerged as a new identity marker, while Azerbaijan explores potential imaginary bonds that extend beyond its borders. As both nation-states undergo unprecedented transformations, there arises a question of how to address the Soviet legacy and the inherent conflict surrounding “making” the Armenian-Azerbaijani border.

This paper aims to analyze the dynamics of the border dispute and identify the challenges facing Baku and Yerevan. The paper begins by providing a comprehensive account of the events that have transpired on the ground, offering readers a clearer understanding of the operational situation. Then, it delves into an analysis of the dynamics between the parties. Finally, the paper concludes by presenting some policy actions that could contribute to addressing the situation effectively.

Situation on the Ground

The Armenian-Azerbaijani border dispute revolves around determining the precise location of the international border and whether adjustments to the Soviet-era borders are necessary for certain reasons. Despite being inherently complex, breaking it down into manageable components — such as disputes over exclaves, border villages, uninhabited areas, and the selection of maps — can aid in better comprehension of the situation on the ground.

Exclaves

For several months, exclaves have been at the epicenter of the border dispute. Exclaves originated in the Soviet era, at the time these territorial “anomalies” had little impact on the lives of their residents due to the absence of physical borders. Nevertheless, when the military conflict erupted in the 1990s they became primary targets due to their vulnerability of lacking a territorial connection with the mainland.

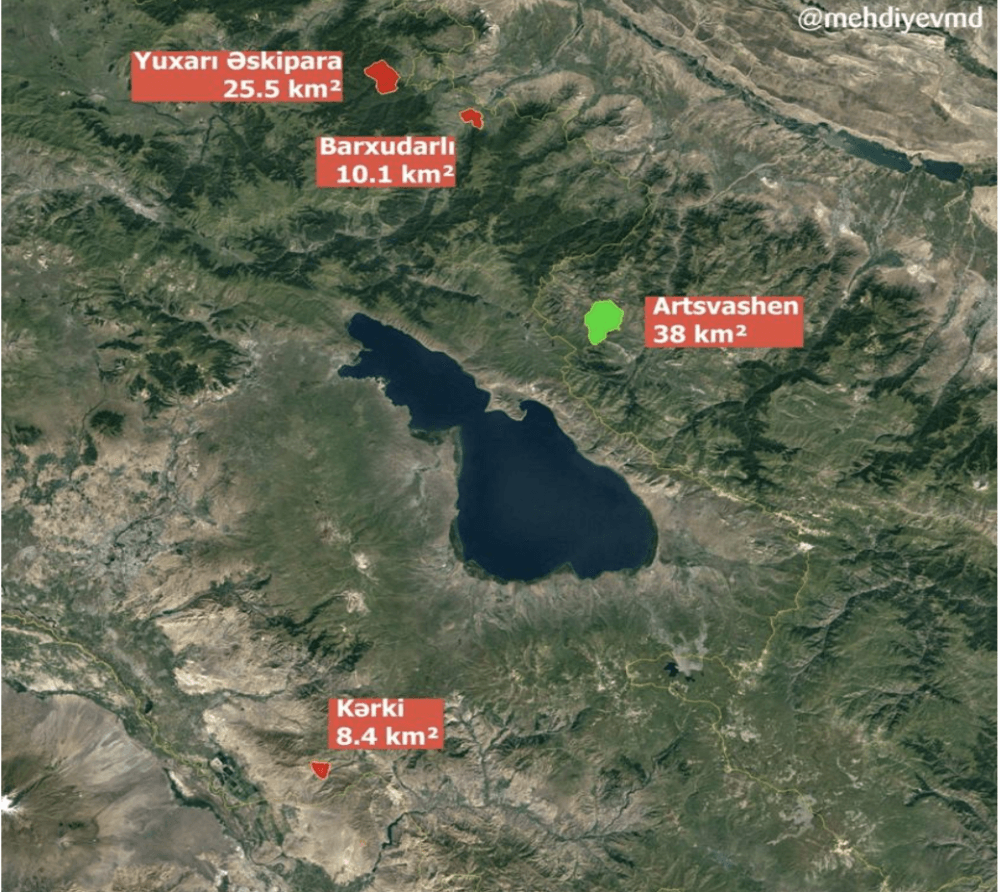

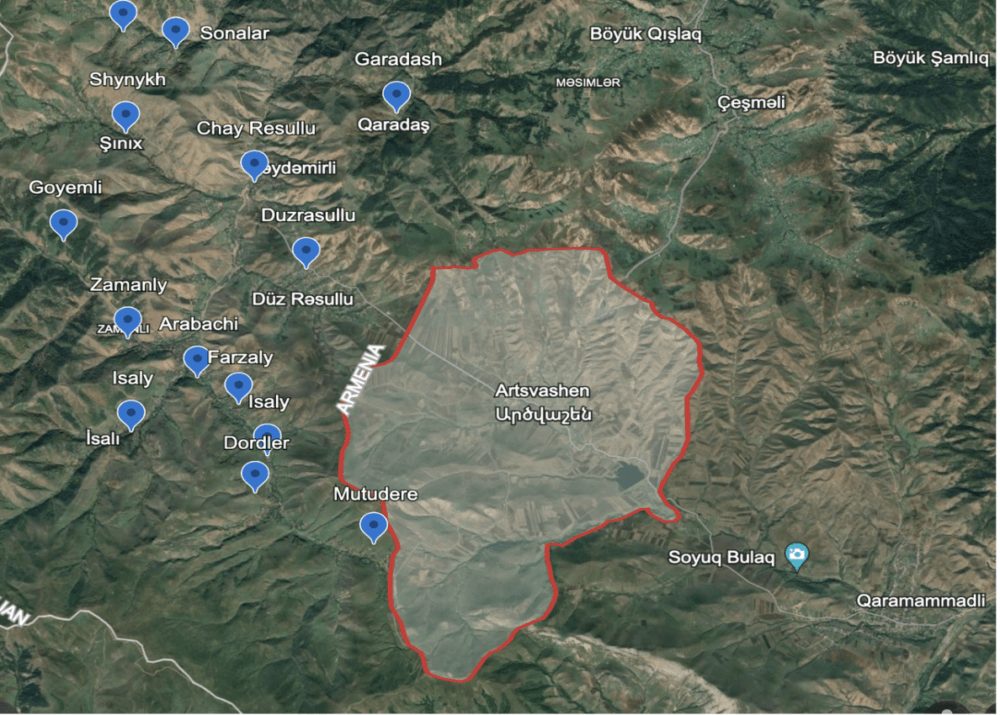

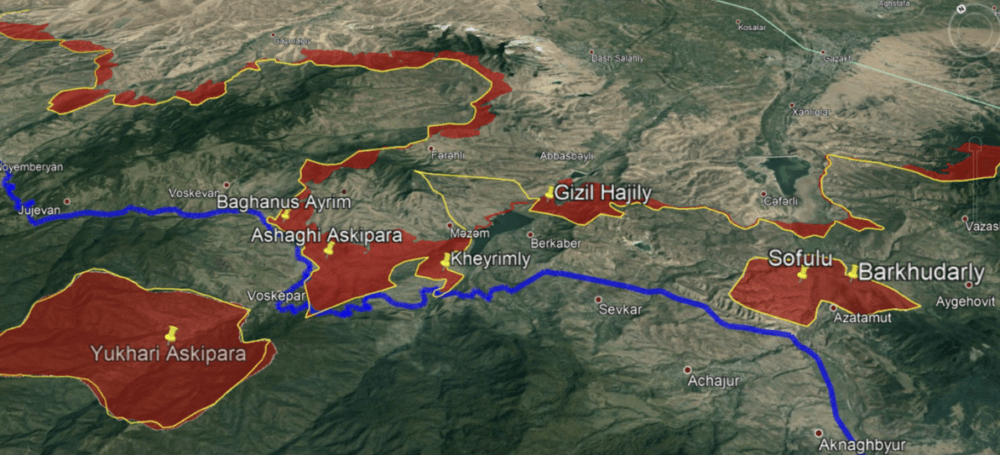

Currently, the dispute centers around five exclaves; Azerbaijan controls an Armenian exclave (Artsvashen), while Armenia controls four Azerbaijani exclaves (Yukhary Askipara, Sofulu, Barkhudarly in the north, and Karki in the south). In terms of size, the Armenian exclave covers a little more than 38 km2, whereas the combined territories of the four Azerbaijani exclaves amount to about 44 km2.

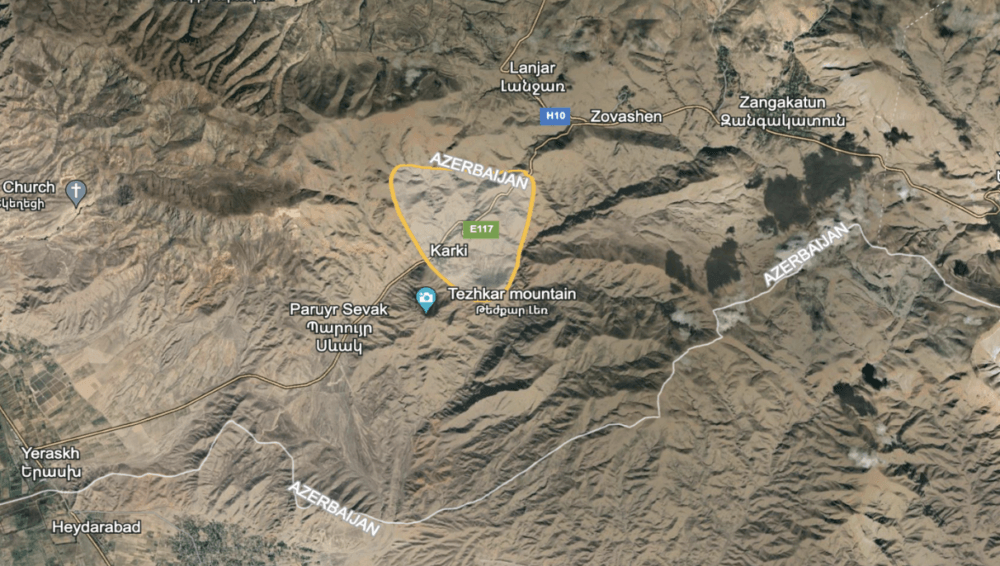

While both countries effectively control each other’s exclaves, their roles and potential losses stem from entirely different perspectives. Azerbaijan, for instance, would rather endure local connectivity and economic issues in the case of Artsvashen’s return to Armenia. On the other hand, losing control over Azerbaijani exclaves would pose significant political, connectivity, and to some extent, security challenges for Armenia. For example, the primary highway (H8) that links the northern and southern regions of Armenia traverses the territory of the Karki exclave.

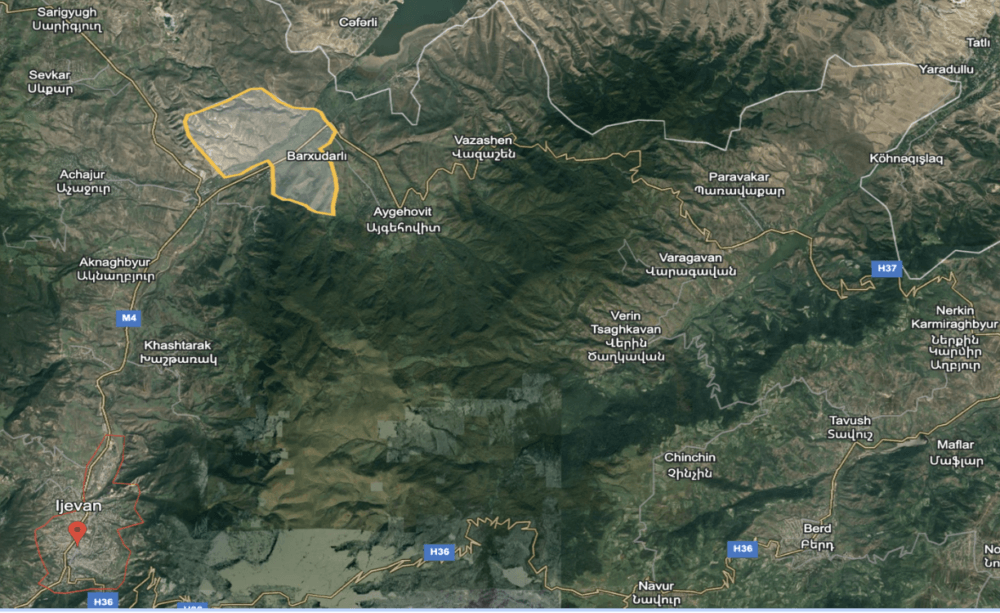

A similar situation exists in the north, where one of the highways connecting the villages of the Tavush marz (the Aygehovit-Nerkin Karmiraghbyur sector) to Ijevan passes through the Sofulu and Barkhudarly exclaves. To bypass the exclaves travelers would have to cover a distance of 81 km via the H36 highway to go from Aygehovit to Azamut, though these two villages are only 5 km apart.

On the Azerbaijani side, the primary road connecting 17 villages in the Gadabay rayon to the regional center passes through the Artsvashen exclave. Opting for an alternative route would require village residents to travel over 130 kilometers to reach the center of Gadabay.

Border Villages

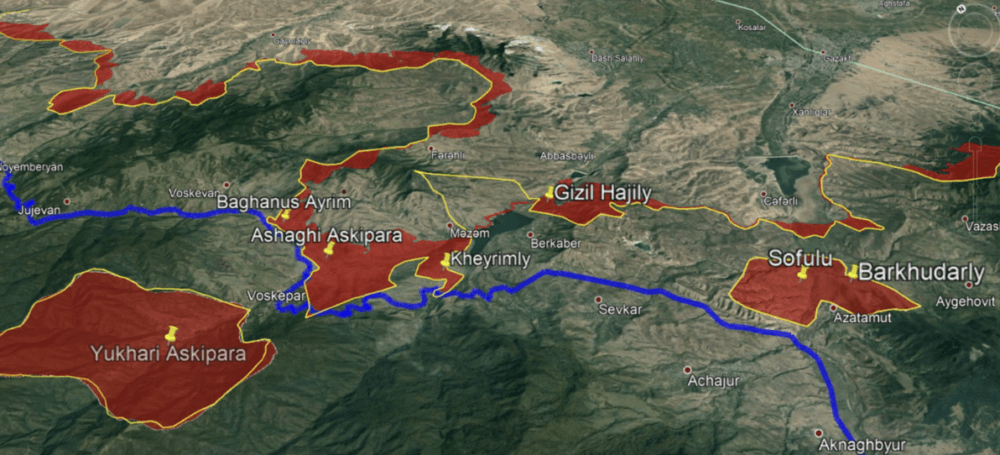

The northern border villages are at the center of another contentious issue. In the 1990s, Armenia gained military control over four Azerbaijani villages near the northern border: Baghanis Ayrim, Kheyrimli, Ashaghy Askipara, and Gyzylhajili.

Although these four villages, now under Armenian control, are mostly in a state of ruin, a situation akin to that in Karki is mirrored here; one of the primary highways (M16/H53) leading to the Armenia-Georgia border enters and exits what is legally Azerbaijani territory five times, with the portion of the road inside Azerbaijan spanning more than 2 km in total.

A situation similar to this occurred after the 2020 war, resulting in the transfer of twelve houses in the village of Shurnukh in Armenia, as well as some sections of the Goris-Shurnukh Road and the Kapan-Chakaten Road, to Azerbaijani control.

No Man’s Land

The absence of physical borders between independent Armenia and Azerbaijan paved the way for territorial advancements into uninhabited areas during military escalations. Such territorial advances occurred initially during the First Karabakh War and later during border clashes following the Second Karabakh War.

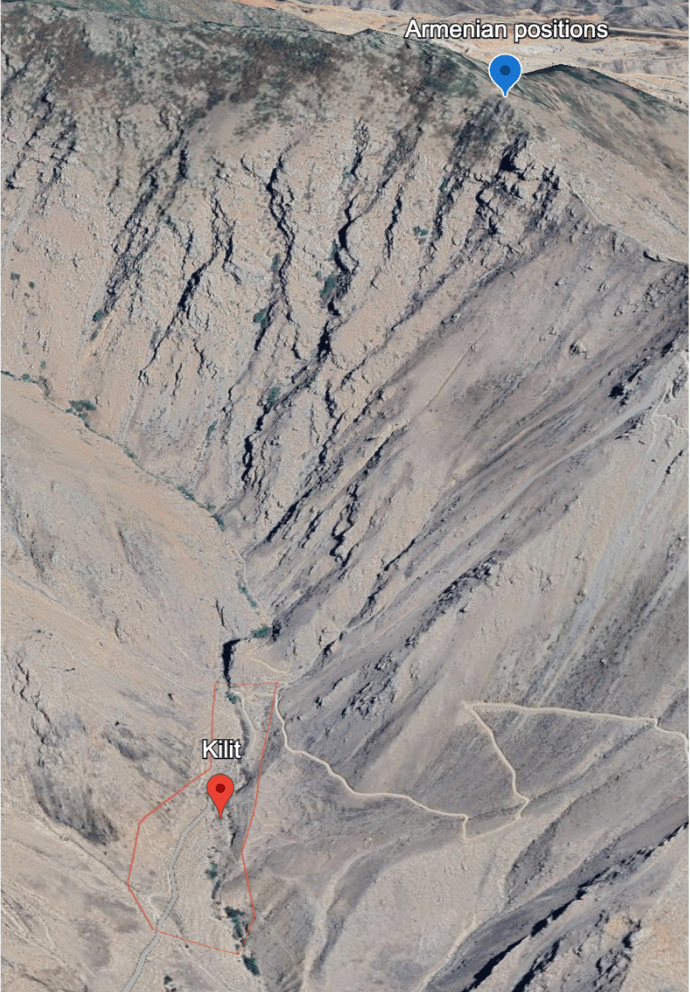

While the areas primarily taken over were uninhabited, such as mountains and hills, this situation has posed numerous challenges and made life more problematic for nearby communities. For instance, due to Armenian troops’ advancement in the direction of Nakhchivan in 1992, the residents of the Gunnut (Sharur rayon) and Kilit (Ordubad rayon) villages were compelled to evacuate their homes, resulting in the villages becoming ruins.

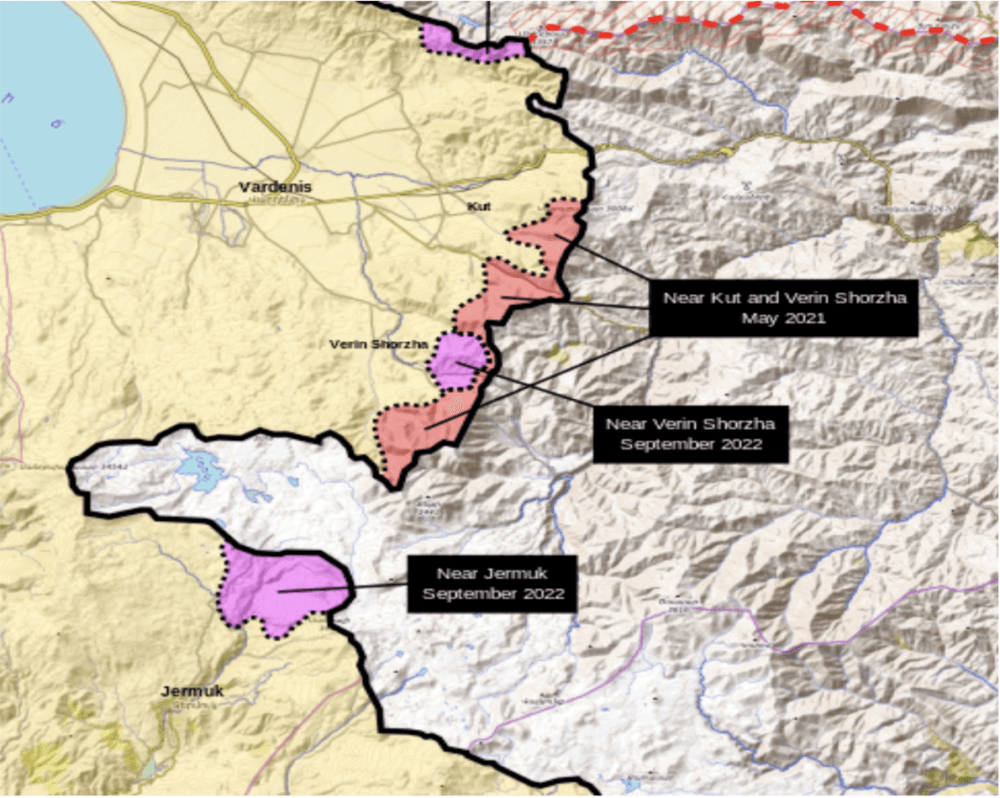

When Azerbaijan regained control over the Kalbajar, Lachin, Gubadly, and Zangilan rayons in 2020, a new sector was incorporated into the Armenia-Azerbaijan border theater. Border clashes in May 2021, November 2021, and September 2022 resulted in the Azerbaijani side establishing military control over a total area exceeding 150 square kilometers in the Gegharkunik, Vayots-Dzor, and Syunik marzes of Armenia. This situation particularly jeopardized the communities residing in nearby areas, including the town of Jermuk, the villages of Nerkin Shorzha, Verin Shorzha, Khnataskh, Tegh, and so forth.

Maps

One of the challenges within the Armenia-Azerbaijan border dispute pertains to the choice of maps used in the demarcation and delimitation process. Armenia supports the use of maps prepared by the USSR General Staff in 1975. These maps, based on post-WWII photographs, offer detailed depictions of the administrative borders of Soviet republics before the USSR’s dissolution.

Azerbaijan advocates for using a set of maps rather than relying on a single map, specifically, looking at maps predating the Second World War. Although the availability of detailed maps from that period is lacking, the era coincided with the initial stages of Soviet border-making policies, notably between 1921 and 1930. It was during this time that the contours of the borders of Soviet republics were first defined, resulting in some territorial exchanges. While these exchanges often involved non-residential areas like agricultural and grazing lands, certain instances impacted settlements (such as the transfer of Nrnadzor to Armenia in 1928).

From the Ground to the Dynamics: Who Wants What?

The border dispute dynamics have undergone unprecedented transformation over the past four years; Armenia has relinquished its advantageous pre-2020 position to Azerbaijan to such an extent that describing the current state of affairs as anything less than acute power asymmetry falls short.

The dynamics are inherently complex and encompass multiple layers. The legal layer, rooted in the uti possidetis juris principle that legitimizes pre-sovereignty (in this case, Soviet era) borders, predominantly favors Azerbaijan concerning exclaves and border villages. As recognition of territorial integrity comes without reservations, Armenia is left with no choice but to recognize Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity, including exclaves and border villages. Given that eight villages are Azerbaijani per international law, any negotiations on potential territorial concessions in this regard is likely a non-starter, as Azerbaijan is less likely to easily shift from its established position on this matter.

Finding a bargaining chip with Azerbaijan on this end is particularly challenging due to the requirement for any territorial concession to be approved through a referendum, as stipulated in Article 11 of the country’s constitution: “State borders of the Republic of Azerbaijan may be altered only in accordance with the will of its people by means of a referendum held by Milli Majlis of the Republic of Azerbaijan.” The difficulties extend beyond the legal layer; the operational layer further diminishes the likelihood of negotiations over exclaves. Azerbaijan’s exclaves are not only larger in size but also strategically more significant, exerting control over Armenia’s transport arteries.

While this legal layer does legitimize Armenian control over Artsvashen, the associated cost — returning eight Azerbaijani villages, with far-reaching implications for the country’s connectivity — renders this option less appealing for Yerevan. A hypothetical approach to nullify the legal layer would involve Armenia not recognizing Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity, but such a stance would introduce a new set of complications.

The legal layer is a rather punitive reference point when considering territorial advancements in uninhabited areas, as both parties have crossed the Soviet-era borders under various circumstances. In this context, it is the operational environment that shapes the parameters of bargaining space. Given Azerbaijan’s advantage in terms of the size and strategic location of such areas, it is likely to leverage these factors in negotiations to obtain concessions for a potential withdrawal. This is where the potential use of pre-WWII maps comes into play, serving as an additional constraint on bargaining space by introducing hypothetical territorial adjustments, with some sources suggesting an estimated range of 200-300 km².

The existing acute power asymmetry visibly limits the room for potential bargaining, as the positions of the parties stand on rather tactical extremes. Additionally, considering the protracted nature of border delimitation and demarcation processes, along with the behavioral patterns of Armenia and Azerbaijan in negotiations over the past 30 years, it seems plausible to anticipate that the Armenia-Azerbaijan border dispute could evolve into a lasting rivalry, with no political resolution, leading to recurring cycles of violence, akin to the border dispute between India and China.

What to Do?

A viable and “win-win” solution to the border dispute could involve the swap of exclaves, thereby legitimizing the current status quo, the return of border villages, the withdrawal of troops to the 1991 Soviet borders in all directions, and relevant territorial and/or logistical adjustments for transport lines crossing the border areas.

However, as previously mentioned, operational conditions present significant obstacles to such a resolution. Given the existing acute power asymmetry and the limited bargaining space available, it is worth considering ways to enhance the potential for negotiations. The following steps could potentially shift the situation in a positive direction.

- To avert the escalating danger, it is imperative to promptly take preventive measures. While international engagement on both ends could potentially yeild a positive impact, it seems challenging given the current conditions, to anticipate Azerbaijan agreeing to any form of international intervention. Nevertheless, enhancing the operational capabilities of the EU Monitoring Mission in Armenia (EUMA) could serve as an initial step.

- Yet, more significantly, the EU should engage in substantive negotiations with Azerbaijan in order to institutionalize communications between EUMA and Azerbaijan. If this occurs, EUMA could act as a facilitator in terms of contact between the parties and, to some extent, serve as an intermediary to prevent potential incidents.

- The international facilitators/mediators can contribute to expanding the bargaining space. The border issues have been negotiated through bilateral discussions and have also been a subject of talks mediated by Russia and facilitated by the EU and the US. Considering the limitations Russia faces in this regard, the EU stands out as the primary actor with the potential to broaden the scope for bargaining if reaching an agreement on border issues is contingent on “peace dividends.” Examples of such dividends may involve investment packages for border regions, employing various financial instruments in bilateral relations (such as investing in the reconstruction of territories and aiding demining efforts in Azerbaijan, or supporting the rehabilitation of transport infrastructure in Armenia).

- Given the complexities inherent in the border dispute, particularly concerning the exclaves, adopting progressive territorial arrangements could offer a more manageable and less politically charged pathway. This approach would allow both parties a flexible framework for negotiations. It is crucial to ink nuanced agreements that would, at the very least, provide a structured framework for future border negotiations.