“Dear Armenian citizens of Georgia, don’t vote for 41, for the “Russian Dream,” which is trying to spread Armenophobia and ethnic discrimination in our united and EU-oriented society,” heard in Armenian from the stage of the opposition protest on October 20, days before the Parliamentary Elections in Georgia.

«Վրաստանի սիրելի հայ քաղաքացիներ, չտա՛ք Ջեր ձայնը 41 համարին՝ Ռուսական Երազանքին, որը փորձում է հայատյատություն և էթնիկ խտրականություն տարածել մեր միասնական, և Եվրոմիություն գնացող հասարակությունում»:

Giorgi Tumasyan, the chairman of Georgia’s Armenian community platform, was invited by the protest organizers to speak as an Armenian representative.

He says he has been the only Armenian voice at the protests opposing the Russian-style law over the past two years.

The blossoming of spring in 2024 also brought a new political climate to Georgia, setting the stage for a politically eventful autumn. The largest protests in the country’s modern history, driven by anti-Russian and pro-European sentiments, erupted after the ruling Georgian Dream party attempted to reintroduce the controversial “Foreign Agent Law” (termed the “Russian law” by opposition activists) after failing to get it passed last year due to popular resistance. The anti-governmental protests took to the streets of the capital, Tbilisi, and some other cities in Georgia, lasting for months.

A resident of Nakhalovka in Tbilisi, whom I met at the protests, told me, or rather confessed, that he is an ethnic Armenian. The conversation then took us to the point of “who cares?” He has lived his whole life here and identifies as a Georgian. He simply carries an Armenian identity as well and is unsure what it means to him. And I get it; neither do I.

The protests have been mainly regarded as Georgian. But the question arises: What does it even mean to be Georgian? As a back-handed compliment, I am always told in Georgia, “You don’t look like an Armenian; you look like a Georgian.” The invisible Armenophobia in Georgia always hits you unexpectedly.

How do we know whether someone is Armenian, Georgian, Azerbaijani, or of another ethnic identity? The long-lasting indifference within the Georgian government vis-à-vis ethnic minorities has led to Georgian dominance and the exclusion of ethnic minorities, such as Azerbaijanis (6%) and Armenians, from key political processes. According to the most recent census in Georgia, taken in 2014, ethnic minorities make up 13.2% of the population. Armenians make up 4.5 %, down from 5.7% in 2002.

There is no law in Georgia regulating the rights of ethnic minorities, which leads to many limitations for them, especially in rural areas.

On October 26, Georgian citizens will head to the polls to vote in the first fully-proportional parliamentary elections. Recent constitutional changes have removed the direction of the election of the president, transferring the people’s right to elect the president to the Parliament. For the first time, elections will be held electronically, except in areas with less than 300 people.

Election speeches and posters are ubiquitous in Tbilisi, but few and far between in the villages. The forgotten library and the school building got decorated as poll stations for the special day, and the ruling party’s posters are the main feature in Shaumiani village.

The Election’s Ghost. Shaumiani

In Shaumiani, a village in southeastern Georgia’s Kvemo Kartli region, life seems eerily quiet. The Georgian Dream’s blue election posters stand out against the stillness, evoking a ghostly presence in an otherwise stagnant village.

Shaumiani, home to about 3,000 Armenians, is in a multicultural region where Armenian and Azerbaijani minorities coexist.

To get to the village, I took a 1.5-hour marshrutka ride from Tbilisi to Marneuli; this route was created after Georgian IDPs had arrived. Then, I waited an hour to catch one of the only 4 buses going to the village. Ani [her pseudonym] points at the youngsters in the next row and says, “There should be more buses for students; there are too many of them.” The bus gets full when we leave, and some even stand on the 30-minute ride.

When I arrive, the presence of a journalist triggers some tension in the village. A man named Alik approaches me. “What is the problem?” he asks, right after greeting one another. He repeatedly answers, “Everything is fine in the village; we don’t have problems here.”

Villagers whisper later, “he works with them [Georgian Dream],” and then they add that he is busy these days since he works as a commission member.

The school and the library turned into polling stations in Shaumiani

Since the village had a funeral that day, finding anyone at the mayor’s office was impossible.

Life in Shahumiani is tedious and repetitive for Ruslan Abrahamyan. The elections provide a rare distraction. He says that most villagers don’t even know who the candidates are. Yet they continue to vote because they’ve been asked to or often to maintain relationships with those who benefit from that.

He will also vote. The mayor’s brother is his friend, he says, and he asked him not to miss the elections. There is no mention of whom to vote for; it is just an unspoken expectation to participate.

The people I talk to in the village are very nice and welcoming but not ready to speak openly about politics and elections; they refuse to go on record. They can’t even recall whether there are any Armenian MPs in the Parliament. They haven’t seen their issues addressed, they say. Many say they lack trust in the election process, having grown disillusioned by years of broken promises from previous elections.

There are few work opportunities in the village. Ruslan says that most have learned to depend on themselves for survival, relying on trade as a primary source of income. He himself is unemployed and relies mainly on the 415-Lari Georgian pension. He sometimes reluctantly repairs shoes to keep himself busy, but with great pride, he sells figs from his garden to Russia.

56% of ethnic minorities in Georgia, compared to 39% of the general population, cited unemployment as their biggest issue. In villages like Shaumiani, people don’t recall seeing any programs that would address the issue of unemployment.

By 2022, only 22% of ethnic minorities felt that any political party represented their interests, down from 40% in previous years. Additionally, 74% of ethnic minorities either refused to answer or did not know if any party was closest to them.

Armenian-Georgian Relations and Political Participation of Ethnic Minorities

Georgian legislation does not include a quota system or financial incentives for political parties to facilitate ethnic minorities’ involvement in political processes. So, involving an ethnic minority in the lists is up to the parties.

For this Parliamentary election, the ruling Georgian Party has two Armenian candidates (36 and 68). Giorgi Tumasyan says there will likely be only one Armenian (from 41) and four Azerbaijani MPs (from 41, 4, 5, 9) in the new parliament.

Some opposition parties have included Armenians on their lists, but Tumasyan questions whether they will pass the 5% electoral threshold. Other than that, only one of the 3 main opposition parties has an Armenian on their lists, the highest at 46th place.

“For years, the ruling parties have created an atmosphere in the country where ethnic minorities were seen as pro-governmental by fostering the feeling that voting for them means voting for the state. This narrative contributed to the opposition focusing on the Georgian electorate, leading to less representation from ethnic minorities,” said Tumasyan.

He thinks the Armenian community needs to be stronger and more politicized; otherwise, the current situation makes it difficult to find a good candidate. However, if the opposition tried harder, they would make it possible to have more Armenian representation on their team. He thinks this would make more sense, especially in the context of Armenia taking a European path nowadays.

No minister or deputy minister represents an ethnic minority. Armenian and Azerbaijani representation is also low at the local self-government level.

In Armenia, they say, the most democratic country in the South Caucasus, the quota system already reserves 4 seats for ethnic minorities in the Armenian Parliament, while ethnic minorities make up less than 2% of the total population of Armenia.

According to Arnold Stepanian, there is an invisible ceiling that makes political participation for Armenians difficult, and the community remains underrepresented. Stepanian, the chairman of the Public Movement “Multinational Georgia,” attributes this to ethnocentrism. He argues that ethnic minorities in politics should be represented more, at around 20-25%. However, he notes that even opposition parties are reluctant to involve ethnic minorities, seeing them as unable to mobilize enough votes.

The ISSA’s 2019 report highlights critical barriers to political participation for Armenians and Azerbaijanis: a lack of interest in politics (42.7%), engagement in domestic work (28.3%), and insufficient knowledge of the Georgian language (26.2%).

“At some point, the Azerbaijanis began better integrating into Georgian society, but not the Armenians. While Azerbaijan tries to support Azerbaijanis here, and sometimes too much, then Armenia does nothing for the Armenians of Georgia.” Tumasyan thinks that Armenia should take more responsibility and that the agreement of “strategic relations” between Armenia and Georgia should not be just on paper between the governments, to make it real it should more importantly be between people.

The representation of ethnic minorities in the Georgian Parliament has been low since the 90s. From 1992 to 1995, there were only four representatives of ethnic minorities, primarily Armenian and Azerbaijani: 16 in 1995-1999 and 1999-2004, 12 in 2004-2008, 6 in 2008-2012 and 2012-2016, 11 in 2016-2020, and 7 in 2020-2024.

Armenophobia in Georgia: Reasons and Looking for Changes

Although Armenia and Georgia have not been at each other’s throats in never-ending wars, they have not been besties either.

During the election campaign, a journalist from the pro-governmental POSTV media approaches one of the prominent opposition leaders, Mamuka Khazaradze, and asks:

“Why are you hiding your Armenian descent? Are you ashamed of that?”

In the video, Mamuka Khazaradze is taken aback by the question and tries to understand where she got that information. The video went viral on Georgian social media and again brought up the conversation about how Armenians are seen and targeted in Georgia. Later, Mamuka Khazaradze apologized to the ethnically Armenian people for the systematic discrimination towards Armenians created by government policy.

Armenians in Georgia often feel invisible or marginalized. The latent Armenophobia has created many obstacles but has also pushed many Armenians in Georgia to hide their ethnic identity, with some even changing their surnames.

Giorgi Tumasyan thinks that Armenians play a significant role in fighting this discrimination. The Armenian community and the Armenian government should be able to articulate the existence and definition of Armenophobia. They should take responsibility for acknowledging Armenophobia in Georgia to be able to address it; instead, the Armenian government “has closed their eyes in the hope that it would go away. Instead, it has got even worse over time.”

The predominance of the Armenian population in Tbilisi centuries ago, which made Georgians a minority in their capital city, became a “threat to a small country such as Georgia,” says Arnold Stepanian.

People have a constructed fear of each other. Instead of finding something in common, they fight and compete constantly. Arnold Stepanian recalls deep-seated issues, such as the role of the Bagramyan Battalion in Abkhazia, the status of Armenian churches, and territorial claims over Javakheti, which have fostered a sense of unease between the two groups.

“Also, Russia always tries to divide us,” says Stepanian, indicating that it is one of the factors that affects Armenia and Georgia.

Stepanian claims that discrimination from state structures towards Armenians and their dire socio-economic conditions in Georgia has not been encouraged by the central government alone. Local Armenians involved in politics have also played a role.

For Giorgi Tumasyan, the Armenian MPs in the Georgian Parliament should have an agenda that serves and contributes to the Armenian community. They should speak up about Armenian-Georgian relations and Armenphobia. Unfortunately, he can’t see how this can become possible in the current political system, where political participation is fake, in the face of the four MPs of the ruling party, presumably representing the ethnic minorities in the Parliament.

The Armenian MPs in the Parliament

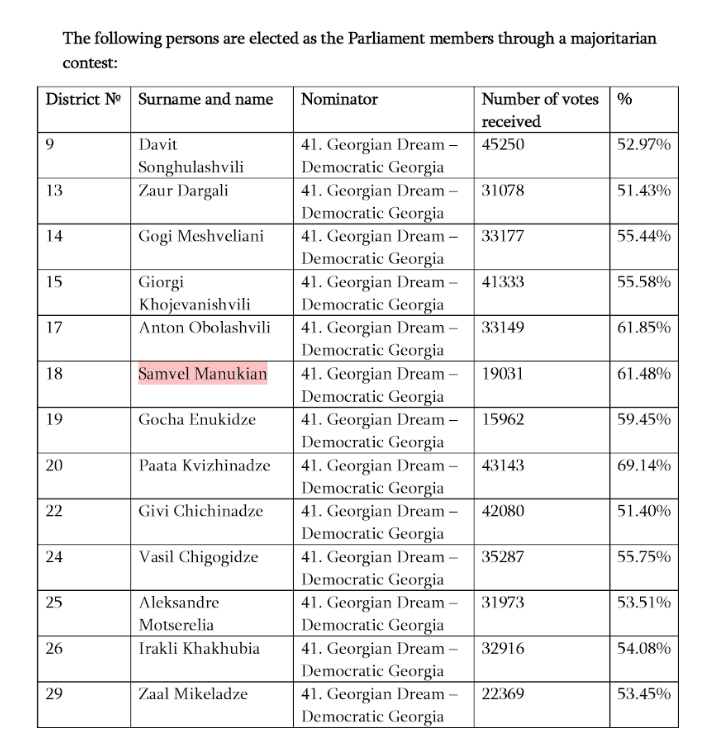

The only ethnic Armenian members of the Georgian Parliament are Samvel Manukyan and Sumbat Kyureghyan from Javakheti. They represent the ruling Georgian Dream party. Both were among the MPs who voted for the “Foreign Agent Law” in 2023 and 2024.

“I promise Armenians that I will convey their voice to the highest authorities of Georgia,” claimed Manukyan in 2020 during his election campaign in Javakheti. Thereafter, he never raised his voice at the Parliament of Georgia, nor did Sumbat Kyureghyan.

In that majoritarian election, Samvel Manukyan won 61,48% of Javakheti’s votes, putting him in third place among candidates who brought the highest votes to the Georgian Dream.

Transparency International Georgia 2023 data highlights that MPs Samvel Manukyan and Sumbat Kyureghyan should have taken legislative initiatives. They are also at the minimum mark regarding the number of initiatives of adopted laws. Over the past three years, only two of their initiatives—one from each MP — have been adopted by Parliament.

According to TI Georgia, corruption and clan-based governance are rampant in regions like Samtskhe-Javakheti, where public officials and Georgian Dream donors have received significant state subsidies. Between 2018 and 2020, 17 entities linked to Georgian Dream donors received roughly 2.24 million GEL (around a third of the amount spent on the region through state programs). Moreover, several entities have contributed substantial donations to the ruling party.

A 2021 report from TV Mtavari revealed that “Ivanishvili’s team has received more than 700,000 GEL in donations” from Javakheti. TI Georgia verified these findings, showing that 87 individuals and five legal entities from the region have donated over 714,000 GEL to Georgian Dream between August 2 and 16 of the same year.

Although mobilizing votes based on a candidate’s ethnicity is common in Javakheti, it does not work in Tbilisi. “People in Tbilisi vote for the party political program, but not for the candidate's ethnicity. This is not the case in Javakheti, where people live in an information vacuum. This is the difference between cities and villages everywhere,” stated Stepanian

Land Ownership and Clan Power

An investigation by RFE/RL exposed the concentration of land ownership in Javakheti among a few influential families. One such example is MP Sumbat Kyureghyan and his family, who own around 3.8 million square meters of land in the region. Kyureghyan was the chairman of the Ninotsminda Municipal Assembly before his parliamentary career. His father, Seyran Kyureghyan, has been the chairman of the District Election Commission of Ninotsminda for more than 15 years.

The family’s land acquisitions are notable. Kyureghyan’s wife, Sasnuhi, who directs Gorelovka Public School No. 2, acquired 157.3 hectares over nine years, including three plots purchased on the same day in 2015. His sister, Leili Markosyan, who also works at the school, owns another 60 hectares. Meanwhile, Kyureghyan’s parents hold over 300 hectares combined in Ninotsminda.

Despite these significant assets, Kyureghyan omitted his parents and children from his 2022 financial declaration. His son, Seyran, owns an additional nine hectares of arable land, which is also excluded from the official disclosure.

Similarly, Manukyan’s financial declarations reveal a questionable lack of transparency. While he claims to own only one inherited house, other properties, including commercial premises and warehouses, are registered in his mother’s name. In 2023, Manukyan purchased a car valued at 179,400 GEL, which he claimed was bought on a loan but repaid in the same year. He also holds shares in three companies—Grand LLC, Krystal LLC, and Geopod LLC—but asserts he has received no income from them.

In 2019, Manukyan was among the 31 MPs fined for incorrectly filling out financial declarations.

Javakheti’s Struggles: Loss of Georgian Citizenship and Emigration

Javakheti, located in southern Georgia, is home to around 150,000 ethnic Armenians. Political participation in the region is minimal, while disintegration and high emigration rates, primarily to Russia, continue to shape the area.

Many Armenians from Javakheti have lost their Georgian citizenship due to forced work migration. Until 2018, Georgia did not allow dual citizenship, causing many to acquire Russian or Armenian passports to navigate the visa challenges between Georgia and Russia. According to Arnold Stepanian, approximately 5,000 Armenians from Javakheti lost their Georgian citizenship and later struggled to reclaim it.

Many of these emigrants returned after the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war, hoping to restore their Georgian citizenship. However, a mandatory Georgian language exam remains a significant barrier for many, particularly those from isolated ethnic minority communities like Armenians in Javakheti, who often lack access to adequate Georgian language education.

“There should be some privileges and exceptions for people born here,” Stepanian argues.

Giorgi Tumasyan says this is one of the main issues for Armenians, and it should have been on the agenda of the Armenian politicians in Parliament.

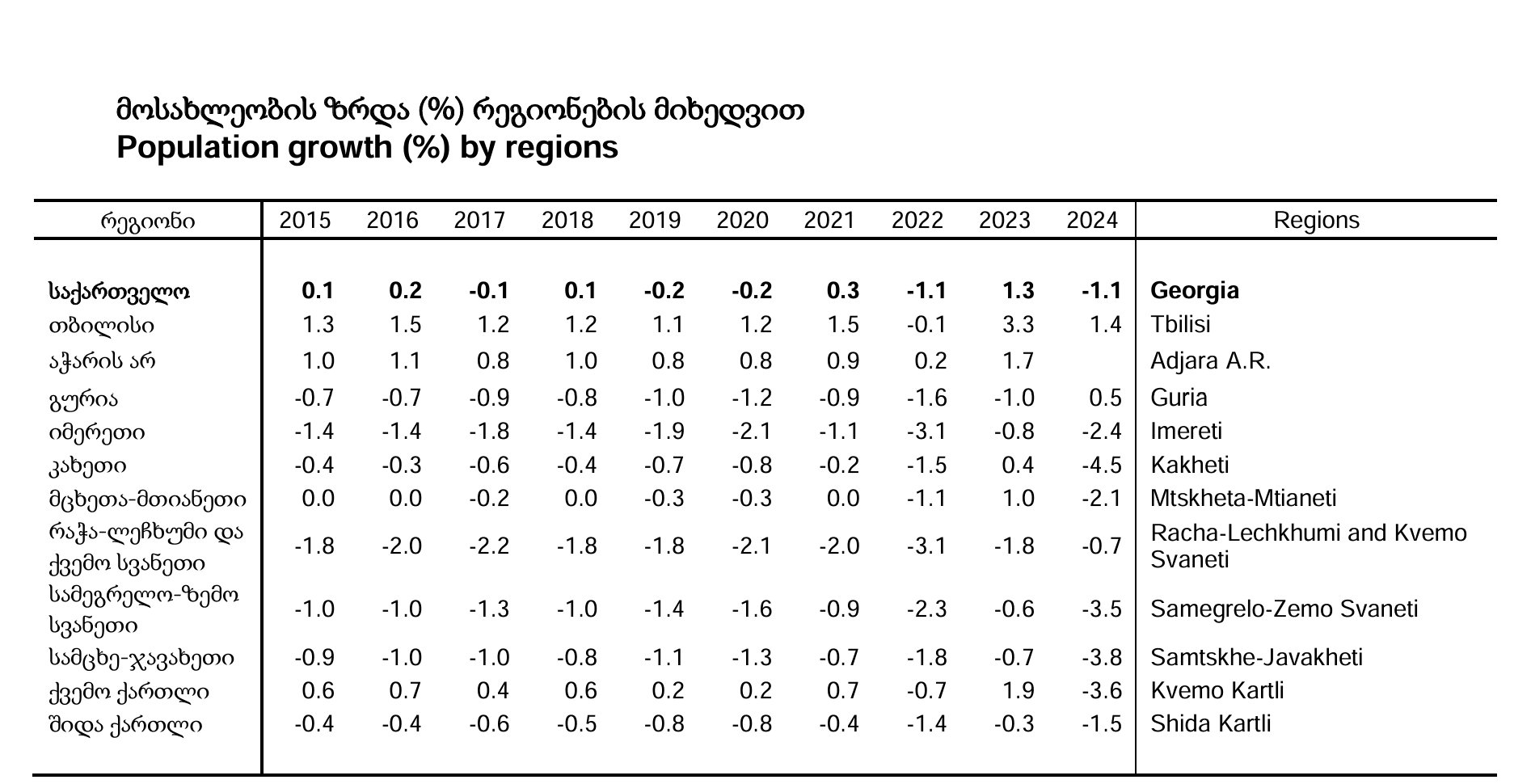

The emigration rate from Javakheti remains high, as agriculture and animal husbandry—the primary economic activities—offer limited opportunities. The scarcity of land drives many to seek better prospects abroad, contributing to Javakheti’s ranking as the region with the second-highest population decline in Georgia.

According to a 2022 CRRC report, 26% of residents in minority areas like Javakheti are likely to emigrate within the next year, compared to 20% nationwide.

The political participation of Georgia’s ethnic Armenian community remains underwhelming, as highlighted in the context of the upcoming parliamentary elections.

While anti-government protests and debates on Armenophobia surface sporadically, structural barriers—such as limited political representation, unemployment, and language challenges—continue to marginalize ethnic minorities. A lack of proactive involvement by both local leaders and the Armenian government leaves many Armenians disillusioned and disengaged. Without substantial reforms, the promises of ethnic inclusion remain distant, perpetuating a cycle of underrepresentation and disenfranchisement for Georgia’s Armenian population.