Everyone knows the Cascade complex in Yerevan — a landmark stairway that connects Yerevan’s downtown center with Victory Park above the city. Five terraces at various levels offer views over Yerevan’s streets and across, to Mount Ararat.

Practically every visitor to Armenia’s capital will drop by the garden courtyard at the base of the Cascade, with its cafés, restaurants, and sculptures. Yet hardly anyone in Yerevan is aware that the Cascade also contains a major memorial to the victims of Soviet repression on its very top terrace. Like the history of the Soviet repressions itself, this Cascade Memorial remains largely neglected.

A handful of Armenians are now trying to restore and recover the memory of the repressions. They see proper commemoration as a step Armenians must take on their path to democracy.

With the remarkable Cascade Memorial already in place, they have a chance to engage a broader audience in the country, as a visit to their annual commemoration ceremony suggests.

On June 14 each year, a group of commemorators assembles at the Cascade Memorial. About twenty to thirty people gathered in recent years.

When I arrived in 2022, a man in a dark shirt was giving a speech in Russian:

‘People didn’t want to talk about it, but we must not be silent because these were crimes.’

The commemorations, organized by researcher and activist Gayane Shagoyan with some support from the Eurasia Partnership Foundation, are dedicated to the victims of the repressions. In Armenia, this focuses mainly on the victims of the 1936-1938 purges, as well as the deportations of 1949. A 2006 law established June 14 as the ‘Day of Remembrance of the Repressed’, as the 1949 deportations from Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan to Siberia began on that day.

Next, descendants of the deported spoke, almost all of them elderly ladies. Several seemed unsure of their command of the microphone. Many families had spent a generation or more in Siberia. In a bitter twist, some Armenians who had left Greece or the Middle East after 1945 to repatriate had been deported. Shortly after reaching their homeland, these hopeful arrivals had been shipped to their freezing exile.

Central to the monument is a large memorial stone, right in the middle, inscribed with the words of Yeghishe Charents, widely considered one of Armenia’s most eminent poets of the 20th century:

“To all your Souls on Fire”

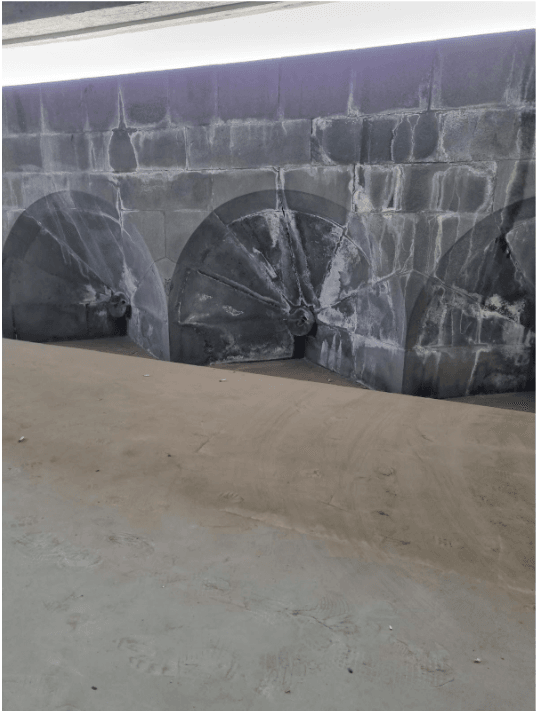

from his poem ‘The Frenzied Masses’. The central stone is illuminated by light that falls in from above through a small cupola that is marked by distinctive Armenian khachkar-style stone carvings, some of which are also outside the Cascade Memorial.

Looking out from within, you see a cinematic sliver through the narrow embrasure: nearby buildings, trees, a Yerevan hillside, and, on a clear day, a sideways slice of Mount Ararat. The proximity to the road adds to the dust into which the one lone boy in the group drew shapes with his feet.

Taken together — a large structure, forbidding yet engaging; containing and preserving the painful memory; brutalist where this style accurately conveys rupture

The Cascade Memorial has been designed at the initiative of Jim Torosyan, Yerevan’s chief architect between 1971 and 1981. Constructing the memorial aligned with the agenda of de-Stalinization in a period of relative thaw. Formally, the monument opened in 2008.

Now, however, this Memorial is mostly orphaned. So far, other than for its opening, no senior government representative has visited the monument. As one organizer explained, when they had called around state institutions to establish who was responsible for the building, ‘no one particularly wants it on their budget, with all the responsibilities also for maintenance.’

Most of the time, the Cascade Memorial stands locked. This makes it a truly unique monument – one that only opens on one day in the year. Perhaps the art that is already at the bottom of the Cascade Complex could also be brought to bear, to draw more people into the Cascade Memorial at its top.

While the Cascade Memorial is mostly inaccessible now, one could think of an automated entrance system in which visitors need to read out the name of one victim of the repressions — name, age, profession, location, date of execution — to gain entry.

With such a system, ideally also devised by artists, the monument could open all year around. This roll call could show, too, how many names still remain to be read to complete the remembrance of all the victims and when, at current levels of visits, that cycle is likely to be completed and the current name will be read and remembered again. (In an expanded version, visitors could be notified once a name has been read and, in a way, has been passed into another visitor’s custody.)

One surprise, as you walk up the Cascade staircase, is that a sizeable portion below its top part remains unfinished — a huge hole you only discover as you level with the yawning gap unseen when looking up from below. Rudimentary foundations are visible, rebar sticking out from concrete. In ascending towards the Cascade’s highest platform, you have to take a major detour.

From the outside, at least, it appears that there remains a gap as well in how Armenians remember their past. Here, too, it may be time to build on the already existing foundations, and connect more directly with the past, as a way of charting a way towards a more viable and inclusive future, one in which Charents’ ‘frenzied masses’ can be read and enjoyed as poetry, rather than as a witness account of how history subsumed and extinguished lives:

To you, comrades near and far, to you, other suns. In other worlds, to all your souls on fire,

To all you burning fires, To you burnished spirits

Who light this untamed darkness called life, and death, To you all who are sacrificed for the sake of light, Greetings.

[This is a more visual version of a longer research essay, first published with Slovo journal in July 2023, see here.]