Meghri, Armenia’s southernmost town, had significant economic and political value during the 70 years of the Soviet Union. The railway passing through it was one of the key aspects of the town’s economy. The transportation of goods boosted the development of the communities living in and near the town. The many factories producing items like wine, canned goods, and clothing became the backbone of Meghri’s economy. The goods produced in Meghri—and Armenia at large—were then transported through the town’s train station to other Soviet republics and beyond.

After the Union collapsed, so did most of Armenia's railway system, as many of the connections linking Yerevan to Armenia's northernmost and southernmost regions, as well as to neighboring Iran, passed through Azerbaijan, Armenia’s adversary in the first Karabakh war. In 1993, after Armenian forces took control over Kelbajar, Turkey also closed its border with Armenia. The Spitak earthquake in 1988, the first Karabakh war in the 1990s, and the mass privatization that followed Armenia’s independence paralyzed the country's economy, driving it into four years of an energy crisis, widely known in the country as the “Dark and Cold Years.” This left very little room for Meghri to grow.

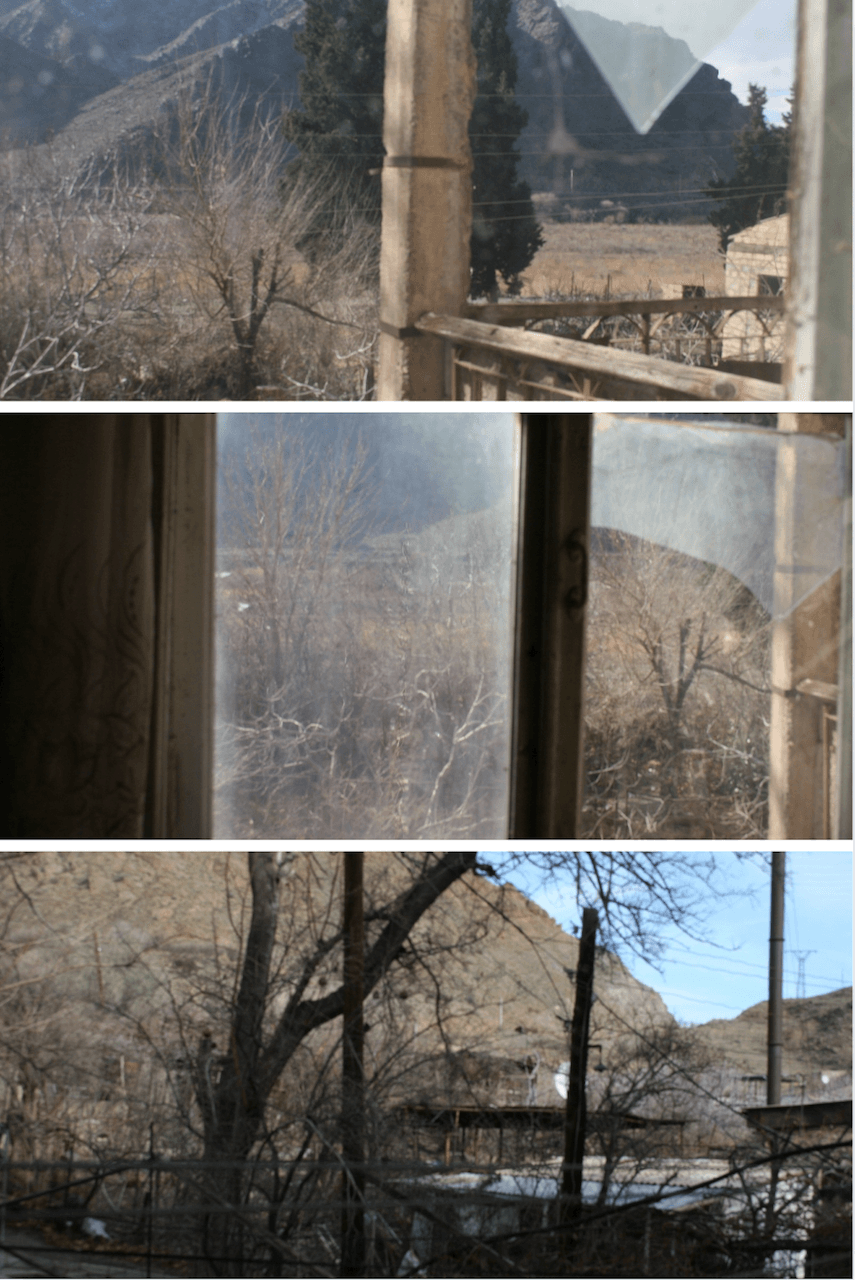

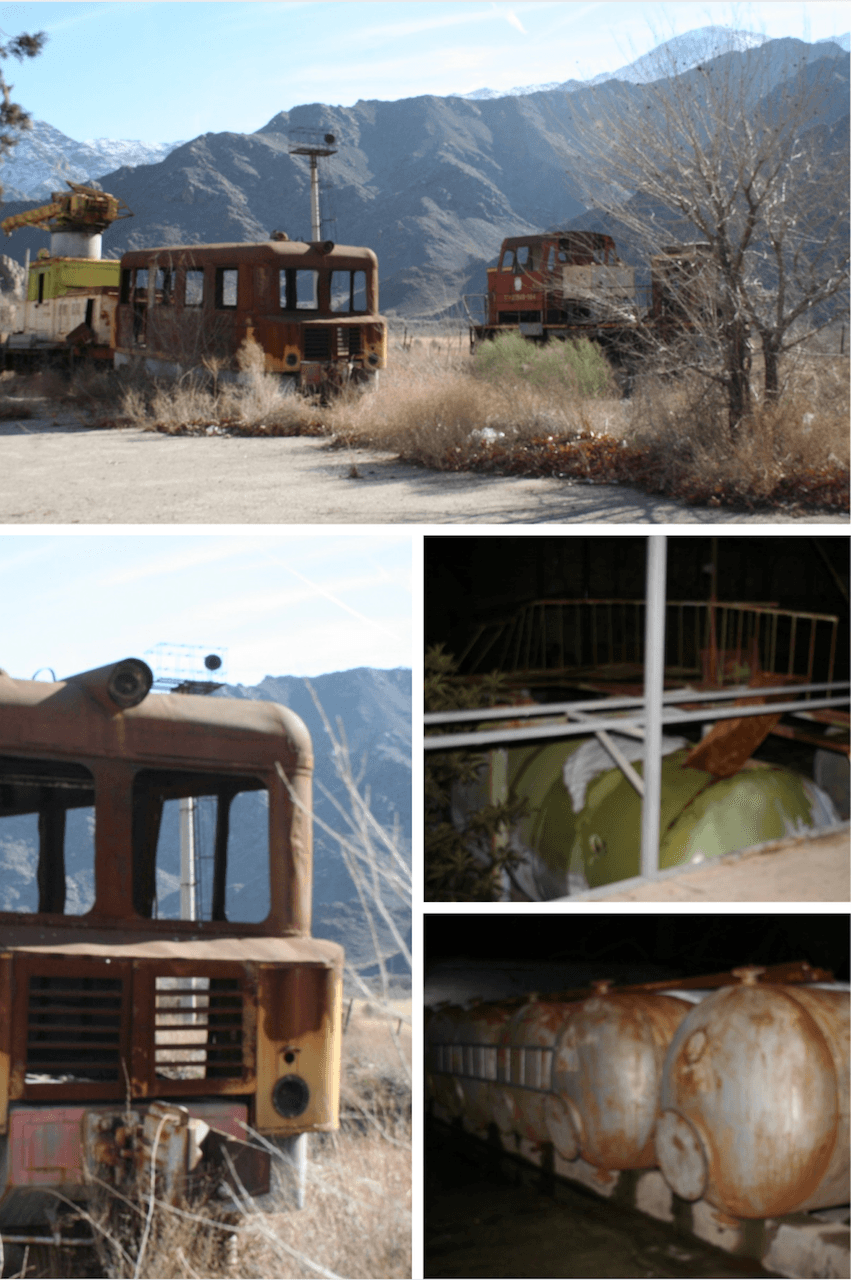

During Soviet times, trains transported a much larger amount of cargo and were generally more efficient than the automobile transportation currently used in Meghri. Several factories in the town produced goods such as pebbles, canned products, and wine. Most of them shut down in the 1990s, while the remaining ones have struggled to operate at limited capacity.

Agriculture, particularly fruit production, remains one of the key aspects of the town’s economy.

Ishkhan, a local winemaker, remembers that during Soviet times, his father, who also worked at the Meghri winery, used to produce around 3,000 tons of wine. Since the closure of the Meghri train station, the winery has struggled to survive and grow, with production in the last 35 years never coming close to that number. According to Ishkhan, the main issues are the lack of transport connections and the ongoing search for suitable markets. He is hopeful about the planned North-South route, a project encompassing a network of ship, rail, and road routes intended to connect India and Iran to Europe via the South Caucasus and Russia. In his view, this corridor will boost both tourism and agriculture in the town while also making cargo transportation much cheaper.

One of the key obstacles to finalizing this corridor is, of course, the closure of Armenia’s borders with Azerbaijan and Turkey, which severely limits the capacity of Armenia’s railway system and trade routes, hindering the country’s ambition to become a crossroads for regional and international trade.

Armen, who currently works at the copper-molybdenum plant in Agarak (another town on the Armenia-Iran border), recalls that Meghri was once connected to Armenia by the now-defunct railway. Trains used to arrive from Baku through Zangilan to Meghri before continuing to Yerevan. The connection to Iran also relied heavily on the railway system, with automobile roads being built in the later decades of the USSR. These connections enabled Meghri to sustain a vibrant system of factories producing fruit, canned goods, and clothing. According to Armen, most of the machinery from the factories that shut down in the 1990s was sold as scrap metal, along with much of the railroad infrastructure.

The migration wave from Armenia in the 1990s also affected Meghri. Mass privatization forced many residents to move to Yerevan or leave the country altogether. Armen recalls that during the first Karabakh war and the postwar period of the 1990s, much of the trade in Meghri and surrounding regions was not money-based but instead relied on bartering. He notes that, although rare, the practice of exchanging goods still exists in the region today.

A lot has changed since then. As a border town, Meghri still depends heavily on cargo transportation. Armen notes that the roads have significantly improved over the last 10–15 years, yet the town’s long distance from Yerevan remains an issue. The centralization of Armenia’s economy around its capital has forced many residents of provincial and border communities to relocate their lives and livelihoods to Yerevan.

Negotiations around the North-South corridor have been ongoing for a decade. One major challenge to the project’s implementation is, of course, the continued closure of Armenia’s borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan, which has placed the country in a de facto semi-blockade.

Since the second Karabakh war in 2020, talks on normalization have resumed between the Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Turkish governments. However, the viability of these negotiations remains uncertain, especially following Azerbaijan’s offensive on Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023 and the resulting exodus of the entire Armenian population from the region—not to mention the constant escalations along the Armenia-Azerbaijan border.

While some progress has been made in border delimitation and peace talks since 2023, disagreements between the Armenian and Azerbaijani governments persist. These uncertainties not only affect potential investments in Armenia’s border regions but also have been, and could continue to be, weaponized for military escalations.

As the looming threat of war continues to hang over the South Caucasus, the communities furthest from Yerevan remain the most vulnerable.

_________________________________________

The project of the CISR e.V. Berlin "NoBorderSpace" within the "Eastern Partnership Programme" of the German Federal Foreign Office