The stories of soldiers from Armenia and Azerbaijan who went through the war in Nagorno-Karabakh which officially broke out on September 27, 2020, in which they share their experiences with war and views on mandatory military service.

“I keep the blast, my birthday gift”

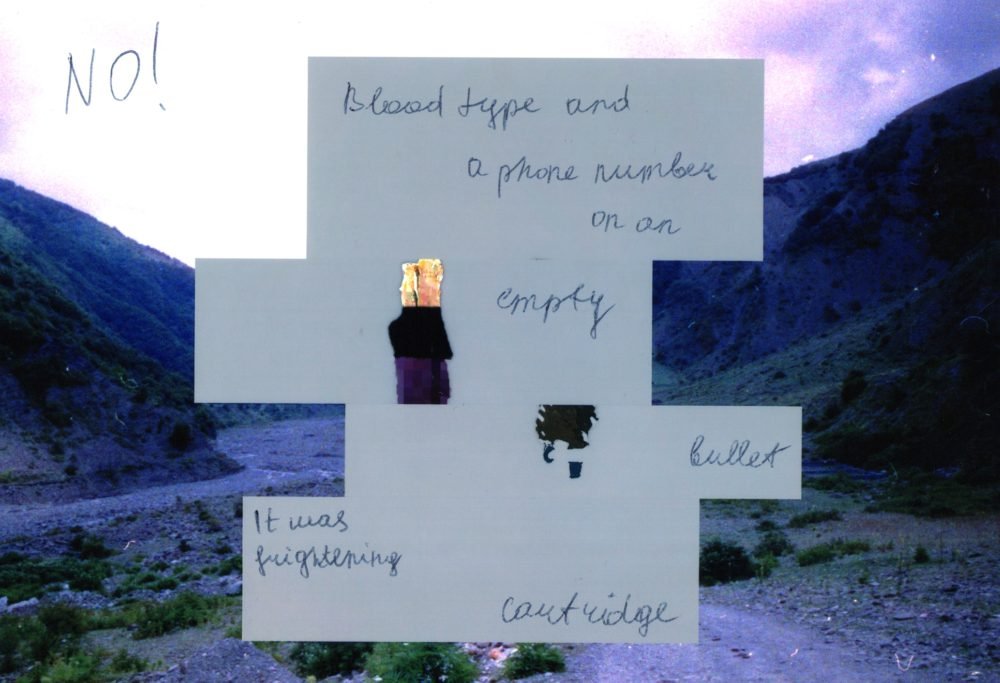

“We were asked to write our blood type and a phone number of a family member on an empty bullet cartridge. It was frightening. It still gives me goosebumps.”

This is one of Yusif Mammadov’s (name has been changed) first vivid memories of knowing the war had officially broken out between Armenia and Azerbaijan on September 27, 2020 in Nagorno-Karabakh while he was on mandatory military draft. Mammadov participated in the battles that took place in the direction of Aghdara (Martakert) district of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Though Yusif says he made lifetime friends from the service and that it taught him to value his time in civilian life, he admits he was never excited about joining the army.

“I didn’t have a reason to go to the army except that it was mandatory, and I wanted to be over with all the legal obligations I had to the country. Now that I’ve seen what it was like, I can say I would have never gone to the army with the right mind. You keep seeing those who will do literally everything just for personal gains, and it’s not worth it.”

Mammadov considers the army a waste of time. “There is a saying that the army service is a school of manliness. You see everything there except manliness. All the free time you have, you spend thinking about and missing your beloved ones. You learn to value time, value your loved ones, value your family. You recall the times you turned down your family asking you to do favors for them while you have to mandatorily fulfill all requests by people you hate, who are in uniform, even if you are sick.”

The war started four days before Yusif’s time in the service was supposed to officially end. His unit was responsible for strengthening the positions already taken by the frontier.

“In two-three hours after the war started we got the news of martyrs and the wounded from the front. When you hear that, you don’t think about dying, you just want to be there and save your comrades.”

“I was looking at young boys, at age 18, getting killed in the field. I think about all the dreams, plans, ambitions they had for life. I remember my own plans and dreams, which I postponed just for being here. All remain incomplete.”

Mammadov remembers his commander and a short conversation with him during the war. He had a newly born daughter whom he had not yet seen.

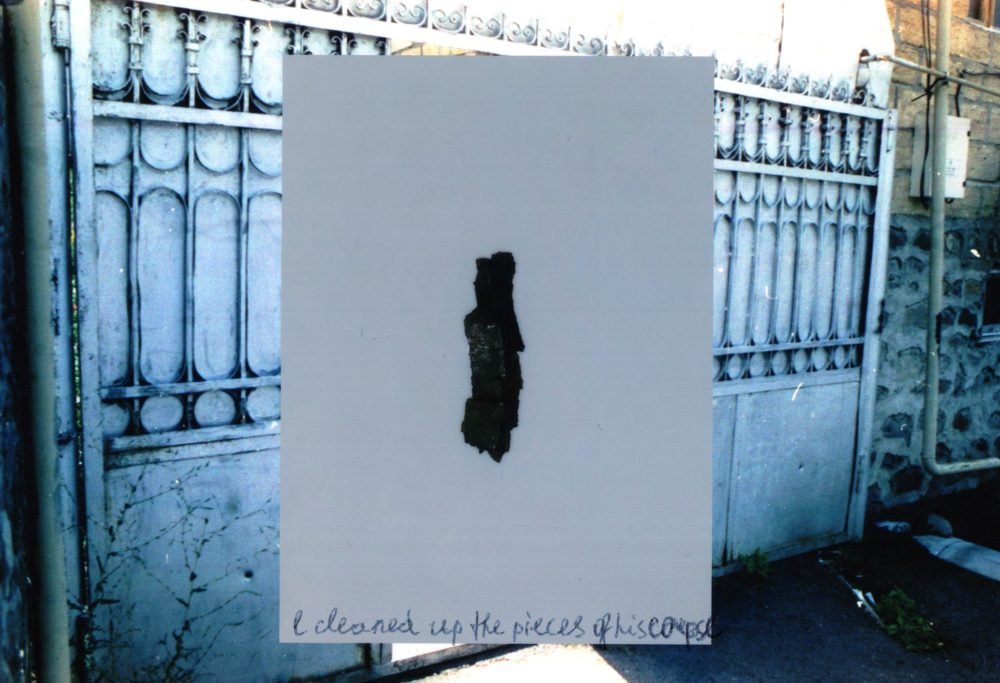

“He was talking to his kids on the phone, I asked about it. A younger daughter of his was newly born, and he hadn’t seen her yet, he said. I said ‘May God let you see your daughter’. After a day or two a shelling hit him and threw him into pieces. I cleaned up the pieces of his corpse. Five minutes pass like an hour. You live five minutes and on the sixth you may be dead.”

Yusif celebrated his birthday with his mates, they brought him a small cake lit with bullet cartridges. His “gift” was not forgotten either, he says.

“It was on the 15th of October, my birthday. Our unit was hit by a shelling. We lay down. When I stood up, another hit the unit and a blast bypassed a centimeter of my ear. I still hear a buzzing sound. I keep the blast, my birthday gift.”

Yusif asserts that he was never a supporter of war. He believes that external forces play a role in fueling conflicts like this one. He remembers that he used to travel to Tbilisi very often and once made an Armenian friend that he kept in touch with on social media.

“But we never discussed the conflict. Because I believe each side has their own truth. Now on both sides there are mothers lamenting the death of their loved ones. A mother is a mother everywhere. What difference does it make if she’s Armenian, Azeri, Russian, or Turkish?”

Now that Yusif has officially exhausted “all legal obligations” to his country, he is prepared to move, find a job, and stay abroad as soon as restrictions on travel are lifted.

Azerbaijan requires conscription for men once they reach the age of 18, with a handful of temporary and permanent exemptions. Temporary exemptions include reasons for education, certain family situations, health conditions, and holding official positions. To qualify for a permanent exemption, one must either hold a doctorate degree, be considered ineligible for service based on medical condition, have reached the age of 35, or be carrying out alternative service.

Azerbaijan’s Constitution allows for alternative service on religious grounds, but there is no subordinate law to outline the process for this right, states Samed Rahimli, lawyer, because the Parliament never adopted a relevant law.

Samed opposes conscription because “it requires people to give up their civil rights and freedoms to submit to the orders of a hierarchical group they are assigned to”. He believes that hierarchical orders such as this in closed groups may lead to human rights abuses due to a lack of monitoring mechanisms.

Practically, Samed says, voluntary service is a viable alternative to mandatory service. It creates more professional standing armies based on contractual service and people exercising their own will. He argues that it is also a better option from a utilitarian point of view if the intent is to better defend a homeland and preserve national security.

“By fault mandatory service is against people’s consent and free will, and from a deontological perspective, people’s consent should be given priority,” Rahimli states.

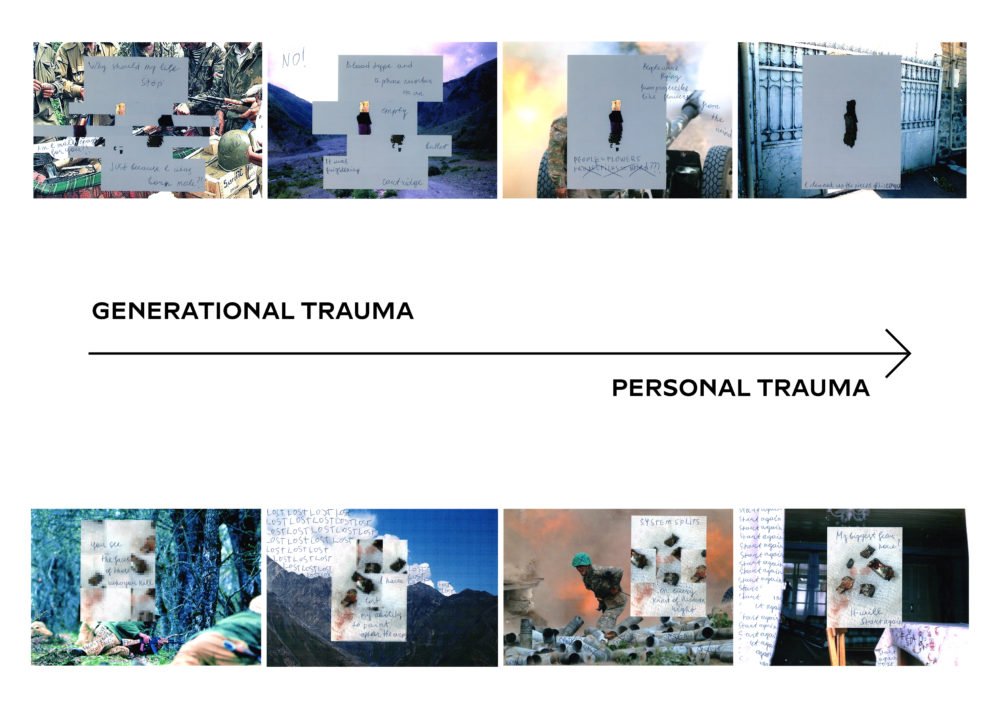

“People were flying from projectiles like flowers from the wind”

“It started at 6:30 in the morning; I was brushing my teeth at the moment. There is nothing in my life that I remember as well as those days, starting from the first second till the last, with the smallest details”

Davit Harutyunyan (name has been changed), 20, had been in mandatory service for 1.5 years when the war broke out in Nagorno Karabakh . He participated in the fighting in the direction of Agdam which was under the control of Armenian forces before the war broke out in Nagorno Karabakh in September 2020. Following the ceasefire agreement that was signed after 44 days of war, Agdam was relinquished by Armenian forces.

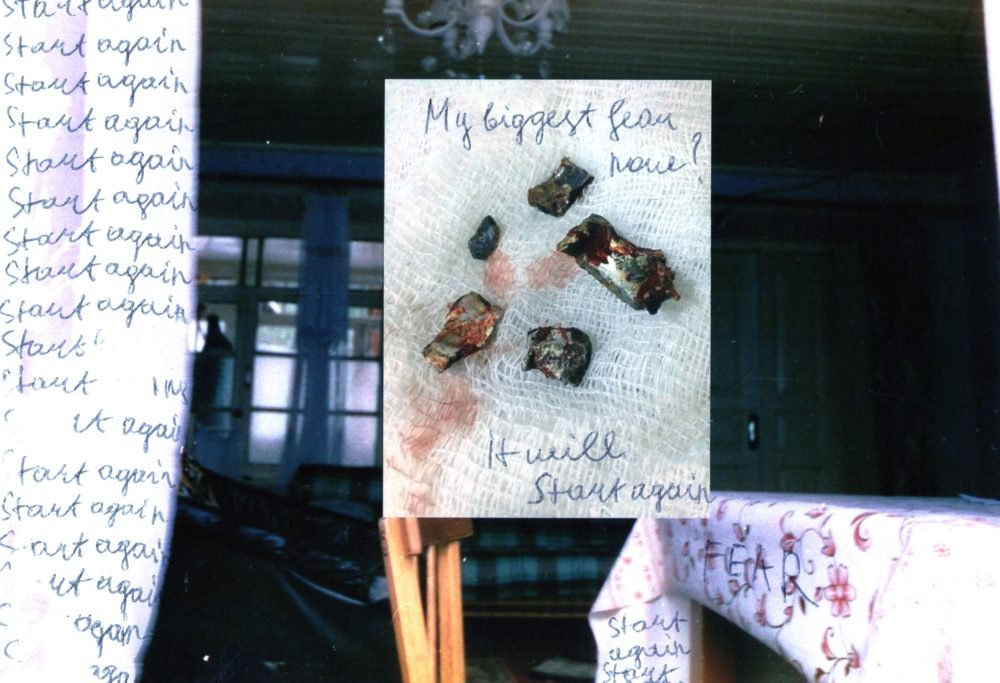

Harutyunyan’s battalion was transferred from Agdam to Hadrut during the war. That’s where he was injured by an UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle). Davit was taken to hospital with 93 pieces of shards in his leg.

He kept the biggest pieces that the doctors took from his leg as souvenirs, but there are still 15 small pieces inside. “The thing is that I am not a soldier anymore, my service came to its end, and they won’t pay for another surgery to take those out”.

Before the start of the war, Harutyunyan’s battalion was on the frontline for four months because of COVID-19. “After staying there for months, we left only for two days. We went down on Friday to have a rest, and on Sunday the war started. Our regiment was being shelled, and we were just standing there looking at what was coming from the sky, because we had never seen anything like that”.

It was the third day of the war that Davit saw blood for the first time. “That day one of my friends lost his hearing; I remember how the blood was going down his ears. And we were carrying the other friend to the trench, because our post had collapsed already. When something cracks near you, you hear the sound, like “tzz”. There are no sounds of the war in my head, only this “tzz”.

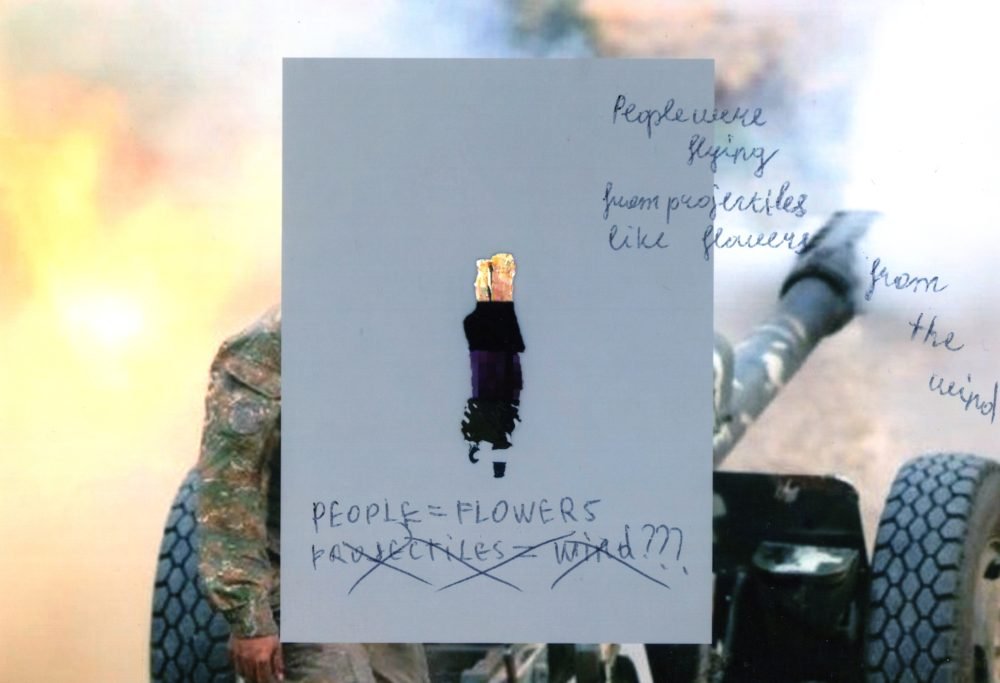

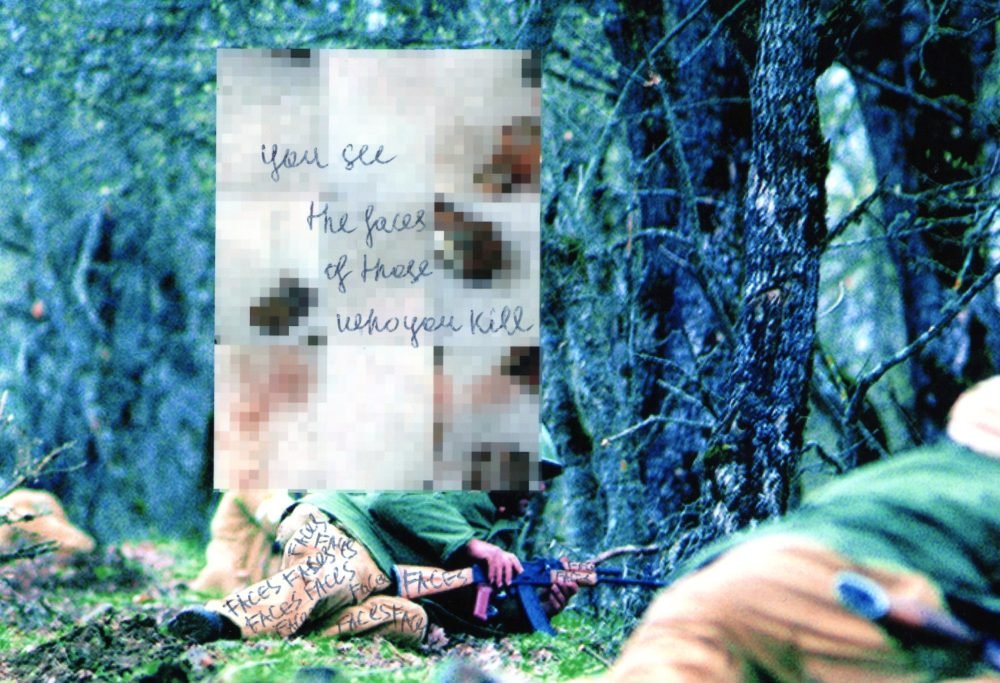

He recalls how they saw on the cameras the people who were shelling them: “You see them coming, and you see the faces of those who you kill. All of it is too abnormal. You don’t realize you killed a man. People were flying from projectiles like flowers from the wind, like dandelions. You don’t realize it’s a person at that moment. You cannot digest that information. Everything happens in a moment and then you have to live with that…”

“I saw the whizz-bang coming. When it hit, it dispersed everyone to different directions. The third one hit just five meters from me; it hit a guy who died immediately. And I appeared in the circle of that fire. At that moment I was thinking: “Is this it?”

Davit was wounded from that shelling, falling on the ground. He recalls throwing his weapons and his bag and walking for some meters with an injured leg, until he fell in a hall near the road: “Then I saw all kinds of shelling hitting the road I was running through”.

Davit says at this moment, when he was lying down bleeding, his only wish was staying alive, even if he lost both legs. “Only after two hours a “kamaz” came for us. I remember the smell of the blood coming from us in the car, I was feeling myself as an animal”.

From Red Bazaar, the strategic village in Karabakh that leads to Shusha/i, the ambulance took them to the hospital in Stepanakert/Khankendi, where Davit had an operation. After the operation another car arrived to take him away. When Davit asked where the car was taking them, the driver answered “To Armenia”. “I think that was one of the happiest moments in my life”, says Davit.

Harutyunyan recalls that he couldn’t get in touch with his family for a week during the war. Then, already in Yerevan, he found out his family members had been trying to contact the Minister of Health, they had been calling hospitals and even morgues to find him. “Only to think how many people actually found their kids in the morgues…”

Davit lost his best friend in the war. They served together during their first three months in the army. “The last day we had a fight. And when I was already in Yerevan, in the hospital, I found out that he died at the frontline. Since then I understood you never know what will happen the next second, you should be kind to the people as much as you can”.

“My biggest fear now is that it will start again and I will appear at the same place. I will do everything in my hands so that this doesn’t happen again, neither to me, nor to my children or grandchildren”.

Before his mandatory service Davit participated in peacebuilding projects with the youth from Turkey. He visited Turkey within the framework of one of those projects. “A year before our visit to Turkey, they came to Armenia, and then we visited them. The girl’s father, whose house we stayed in, was an Azerbaijani. That girl and her family had no hatred towards us”.

Looking down, examining his thoughts, Davit thinks out loud. “I do not have hatred towards Azerbaijanis, and many other soldiers who participated in this war also don’t. I would like them not to have it inside them as well. Because we all saw what the consequences of the hatred are. But till now we haven’t seen what peace can bring to our countries. Maybe we should try and see? There is nothing more important than human life. My life has as much value as the soldier’s life who is standing in front of me…”

“… I am sorry for those lives I have taken. Let them know that there is one Davit in the world who suffers because of that…”

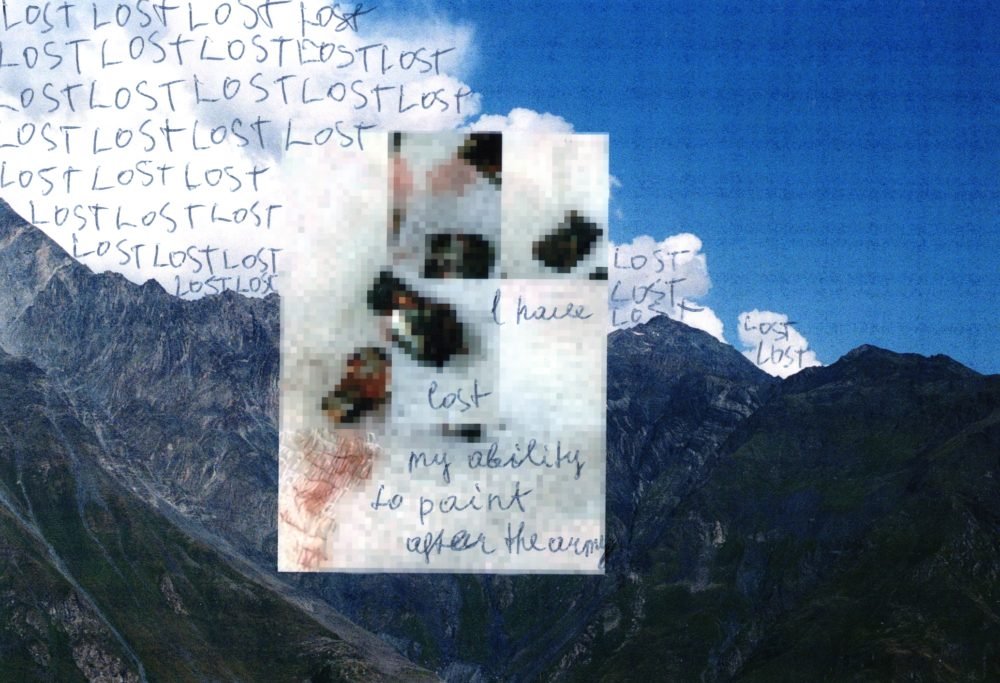

Harutyunyan’s life goal was to become a good artist and a graphic designer. However, he does not paint anymore. “I have lost my ability to paint after the army. I have not been practicing for such a long time, that I just can’t paint anymore. And that is why I left the university also”.

Davit says he is sure that every person who served in the army had been dreaming during the nights before of what he would do if he was home: “I used to dream that I took my girlfriend from the university, we sat in the café, and I was even imagining what we would be talking about”.

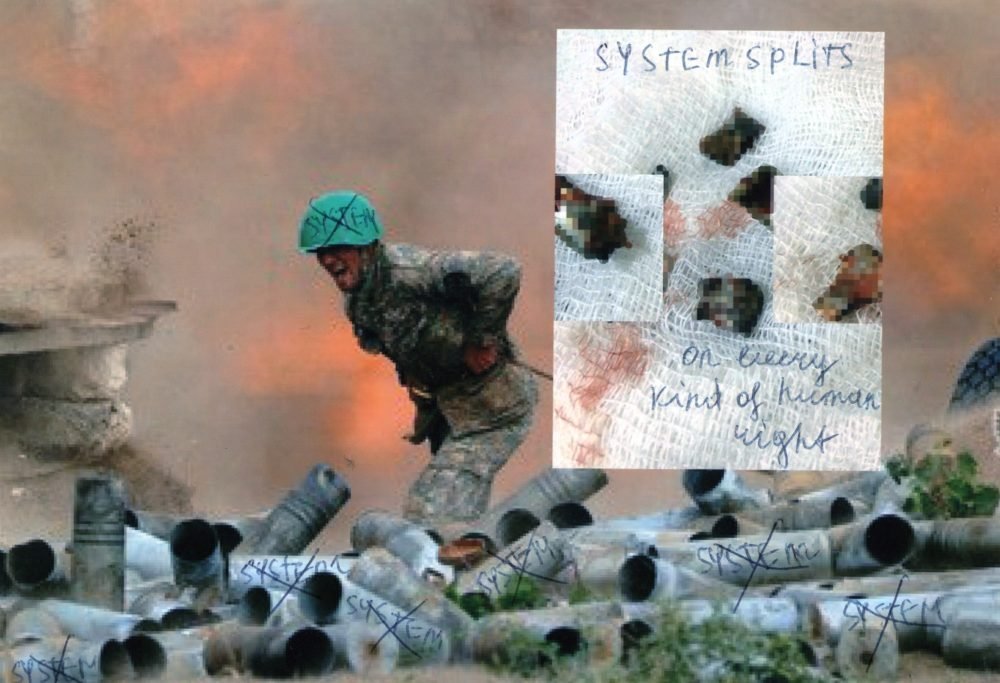

“Whatever basic human rights you know, all of those are violated in the army. There is a system that splits on every kind of human right”.

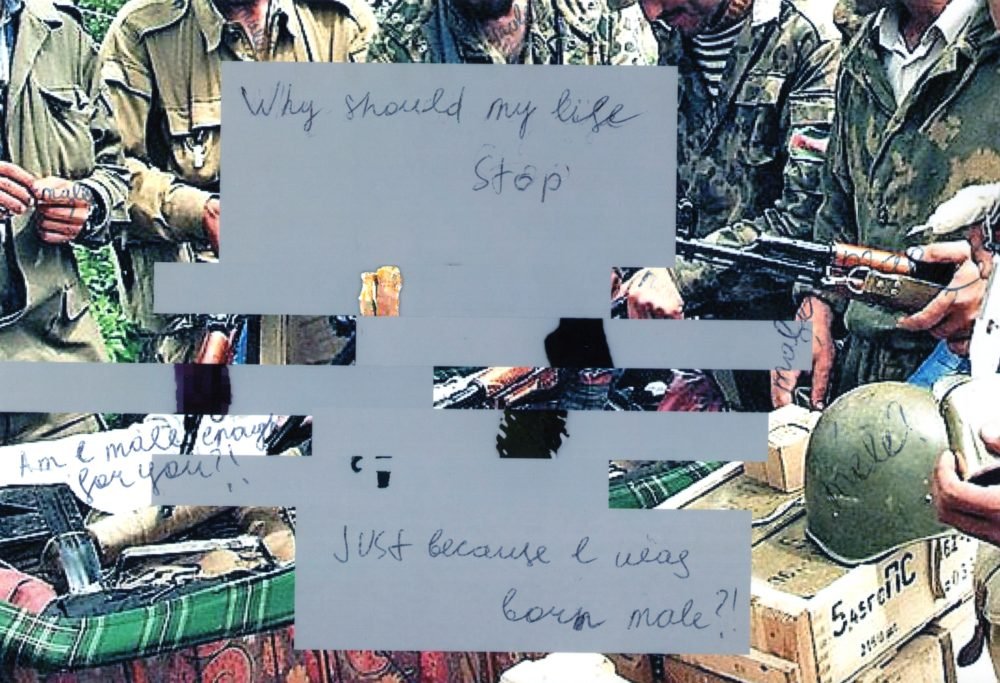

Harutyunyan says it is due to both the level of consciousness and the culture that people don’t talk much about it. “Even my sister who has a very broad worldview used to say ’the guy should serve, he has to become a man’. Okay, I am a boy, but why should I not see my close ones for two years just because I am a boy? Why should my life stop for two years just because I was born male? What kind of prehistoric, Stone Age mentality is that that guy becomes a man only when he serves in the army?”

According to Article 19 of the law on Military Service and Status of Soldiers of RA, Armenian military service is organized through conscription. Male citizens over the age of 18 are required to be drafted before reaching the age of 27. The citizen is fully released from compulsory military service only if he was declared unfit for military service due to his health condition or, if before acquiring the citizenship of the Republic of Armenia, has served in the armed forces of another state for no less than 12 months or had conducted alternative service in another state for no less than 18 months.

"One thing I knew for sure, all the “WeWillWin” propaganda was useless."

Artsrun Pivazyan, 29, a civil society activist, served in the Armenian army from 2010 to 2012. “I had a constant feeling that my life was being stolen for a certain time and I was just waiting to have that time over”, he remembers.

Pivazyan says that the concept of war and the army itself had always been unacceptable for him. “I never thought it was okay to fight for “soil”. Human life, human dignity should have a higher value above everything”.

“I started thinking about justice beyond mandatory service only recently, and maybe that’s because it’s related to my job. An 18-year-old boy does not think about what law is, or what his rights are. Human rights are not considered as a base value within society.”

“First, they make an artificial emotional connection between you and the soil, and make you fight for the soil, and put you in a position when your safety is a problem. Then your right to live is violated… The management level in the army and the military education is very poor. The things that you need to learn, such as geography of the region you are in or first aid, nearest hospitals, that you need in emergency situations, in most cases you actually don’t learn there. Even if you decide that you really want to go to the army, that homeland is so important to you that you should serve and sacrifice your life, still the system works very badly”, says Pivazyan.

In Artsrun’s opinion, the army should not be mandatory; it should be voluntary for both men and women. Yet if it is mandatory — again — it should be mandatory for both genders. In this way both the responsibility and possible sacrifice might be levied upon every member of the society.

“Some of my family members and friends volunteered. At some point I was thinking I need to be by their side. Everyone who left for war needed support, but how it was supposed to look wasn’t clear to me. In despair, once I went to the military enlistment unit to find out where my family members and friends were. I was thinking for some days about a plan to go and bring them back. One thing I knew for sure, all the “WeWillWin” propaganda was useless. My vision of the situation and the possible outcome was different from the one of most of my family members and friends. In some circles we were talking about how it should be stopped as soon as possible.

“There is also the pressure from society that if you talk about the injustice that is lying in the concept of the army, you will be called “not a man enough” or “a Turk”. These expressions are offensive, of course, and sometimes they make a thick and high wall between objective reality and romantic patriotism.”

“I think on both sides people think that during wartime death might happen to a random stranger in the society, but never to them, that it is far away from them. But it’s not always the reality.”

Text by Heydar Isayev, Arpi Bekaryan

Visuals by Naila Dadash-zadeh

Archived comments

Thank you for the truth. One should be enough brave to accept this true. Narrow-minded people like to hang labels, people must realize that they must be above these inert beliefs.