The article presents the preliminary results of research on Russian migration to Armenia and Georgia after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This study is mixed-methods research comprised of surveys (N = 899) and interviews (N = 50). The research team is comprised of members of the studied group, therefore the study also reflects their participant observations and personal reflections. The article outlines the overall socio-demographic status of the migrants, then focuses on their economic decisions and adaptation practices, with as special focus on employment issues. The study also reflects the struggles of planning the future and dealing with the uncertainties of a migrant’s life.

Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 forced many Russian citizens to leave the country. The South Caucasus region became one of the most popular destinations, due to visa-free entry: Russian citizens are allowed to stay without a visa, for up to 180 days in Armenia and 360 days in Georgia. Also, Russian citizens can enter Armenia with an internal passport. Armenia and Georgia are out-migration countries (Honorati, Bartl 2021) with large diaspora communities in Russia, and until recently were not popular destinations among Russian migrants. Now, Armenia and Georgia shifted their role from out-migration to in-migration countries. Alongside Armenia and Georgia, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Serbia, and many other countries have also received a significant number of Russian citizens. The members of our research team moved to Armenia and Georgia, therefore we chose these two countries for the focus of our study. To gather quantitative data we employed a survey, and received 899 responses during the first wave of migration from Russia from March through May of 2022. Survey data contains information about motives for migration and difficulties specific to migration during the war. We also conducted 50 in-depth interviews with people who left Russia during the spring. We analyzed the main features of the narratives used to describe the war, their journey, adaptation practices, and coping strategies in their daily lives.

The features of Russian migration are heterogeneous and often contradictory. The hectic departures and, in some cases, danger in the home country bring the migrants’ position closer to one of refugees. At the same time, they are not refugees sensu stricto, as they did not flee a war zone as such and most were not motivated by political prosecution or the fear of it. In line with this, the later wave of migration spurred by military mobilization stands slightly apart, as people ran from forced military recruitment. In interviews, our respondents emphasized that “real refugees” are those who are now coming from Ukraine, so this status does not apply to Russian migrants. In some ways, recent migrants from Russia are close to another category of forced migration, that is political refugees. Many of our respondents were involved in political protests in the last decade, and some were involved in anti-war protests in Russia since the outbreak of full-scale war. Among the migrants are many representatives of politically vulnerable groups: political activists, journalists, and human rights activists, many of whom experienced political prosecution in Russia. Others who left Russia but did not experience political prosecution emigrated mostly due to reasons of conscience (unwillingness to sponsor the war with their taxes), the fear of mobilization, and an unwillingness to live under a dictatorship.

On the other hand, the current migration has many features of privileged migration and is close to lifestyle migration (Benson and O’Reilly, 2016) or ‘digital nomadism.’ Most of the migrants in this study have savings and often continue working remotely for their jobs in Russia or a third country and have a relatively high income. Migrants represent the practices of the middle class (renting a big flat, using taxi services for everyday transportation, visiting expensive restaurants, paying for house cleaning, etc.) that can be unattainable for locals (see the discussion on “Westerns” in India in Korpela, 2010).

Their impact on the local economy is ambiguous; the presence of new migrants has impacted price increases in the region, and many Armenians and Georgians faced increasing rent costs in Yerevan and Tbilisi following the recent influx of migrants from Russia (Avetisyan & Shoshiashvili, 2022). Another important and distinguishing factor of the current migration is its connection to the imperial history and xenophobia in USSR (Sahadeo, 2012) and Russia. Many people from Armenia and Georgia experienced these prejudices, including ethnic discrimination in the labor market (Bessudnov & Shcherbak, 2020). Some Russian citizens who moved to Armenia and Georgia are carriers of such negative stereotypes and prefer to separate from locals and/or do not take into account this history and the recent conflicts. At the same time, many newly arrived people try to discuss their prejudices to find new decolonial optics through which to view the histories.

In our research, we ask, who are the migrants to Armenia and Georgia and what are their economic strategies? Our research discusses the interaction of migrants from Russia with host societies, their integration, education for their children, their family, relationships with relatives and friends who stay in Russia, and involvement in political and anti-war activism. In this article, we particularly focus on the economic strategies of newly arrived people. What are their professional and educational backgrounds? How and where are they seeking jobs? Do they keep the same jobs they had in Russia or seek new jobs?

The data collected for this research presents initial answers to these questions. Our theoretical framework combines several focal points of migration studies. Due to the specific circumstances of this migration (fleeing the war from the aggressor’s side, often leaving behind an affluent urban life), we found atypical migration strategies. For example, rather than looking for employment in the receiving country, many migrants try to preserve the sources of their income from the country of origin or third countries, mostly from international companies based in the so-called Global North. Moreover, Armenia and Georgia are mostly seen as transit points by many migrants.

Conceptual framework

According to the seminal works of migration research literature, migrants of the same origin tend to concentrate in the same districts and same workplaces (Portes, 1987; Massey & Denton, 1988; Massey, 2012). These processes endorse diasporic ethnic enclaves and facilitate the consolidation of minority entrepreneurship. The studies dealwith the question: How does minority entrepreneurship impact the economic well-being of both migrants and a host society? It should be taken into account that minority entrepreneurship can both contribute to the exclusion of some communities and provide a possibility for newcomers to start a career in a new place in a safe and familiar environment (Hack-Polay, 2019). Another important factor is participants; who are the people who create a small business predominantly with co-ethnics, and who are the employees and clients of minority entrepreneurship? There can be different combinations, e.g. a migrant owner, workers, and a client, a migrant owner and local employees for migrant networks, etc. Russian migrant entrepreneurship in the South Caucasus is still in the early phases of its development, so our preliminary observation can provide only a tentative provisional analysis. Later in this article (Section 4.3) we will discuss Russian businesses in Armenia and Georgia in terms of creating open or closed spaces, lacking support of specific infrastructure for migrants in these countries, and the origins of employers, employees, and clients.

Migrant entrepreneurship also can be viewed as a ‘transnational practice’ which leads to diasporic development (Zhou & Liu, 2017). Entrepreneurship by migrants impacts local life and helps migrants adapt to the local environment. The 2022 Russian migration includes many cases of ‘relocation’ of companies which seemingly reproduce the practices of transnational corporations. Relocation usually describes the process of re-opening the business in a new place, compared to the new term “relocant,” which refers to the privileged position of a person who moved while sustaining their previous job and income. These practices affect dynamics surrounding communication with, and treatment of, employees, recruitment of new workers, adapting salaries and work duties, changing the dominant language at a workplace, and currency. The latter is mainly valid for either very prominent international corporations that can dictate their own rules to the host country, or otherwise, small or unofficial businesses that can evade taxes and legal control. At the same time, these practices are continuously changing, and the topic was largely beyond the scope of our research and requires further investigation.

Methodology

This article is a thorough analysis of both quantitative data, obtained from a survey conducted in March-May 2022, and qualitative data, from interviews conducted in June-September 2022.

Quantitative survey

The survey aimed to identify the social profiles of migrants from Russia in Georgia and Armenia that were then further explored through qualitative interviews (see section 3.2). The survey included 61 questions in total, mostly multiple-choice, and was divided into 6 sections: the process of leaving Russia, reasons and preparation for leaving, life in a new place, plans for the future, professional employment and sources of income, and personal characteristics of respondents and their families. This wide range of questions was driven by the aim to make the scope of the quantitative study as broad as possible. Then, we selected several interesting focal points from this general data to inform our interview design.

The questionnaire was distributed through telegram channels and chats of several types: 1) general large chats and channels on migration and relocation guides (e.g.,“Russians in Armenia,” “Kovcheg,” etc.) 2) migrants’ chats and channels of different cities (e.g. “Gyumri Mutual Help”), 3) professional chats of migrants: academic, IT, etc. 4) other thematic chats (search for neighbors, car drivers, custdev, etc.), 5) other. Data was collected between March 25 and May 6. In total, 1075 responses were collected during this period, from which we selected the final sample of 899 respondents that met our criteria; are of those Russian citizenship who entered the territory of Georgia or Armenia after February 23, 2022.

In-depth interviews and observations

The interview guide was designed chronologically and included a wide range of questions. The main blocks of questions are as follows: social characteristics of the informants (with the exception of potentially sensitive matters); biographical questions about life before the start of the war; memories of the beginning of the war; the decision to emigrate, participation in the protests and anti-war activities in Russia and in the new places of residence; travel difficulties (purchasing tickets, complex logistics, searches and inspections at the borders); the choice of the destination country the early adaptation period in a new place and everyday issues (choosing a city/settlement and finding housing in conditions of price increases, arrangements for bank cards, getting accustomed to protocols and language of communication, etc.); the perception of emigration in immediate circles of contacts (support of / conflicts with family and friends); plans for life in the country or further movement; social circles in a new place (contacts with other emigrants and with locals); ideas about the desired and possible level of integration in the host community; political views in relation to the desire and readiness to return to the Russian Federation; changes in economic situations after moving; dynamics of emotional states from the beginning of the war until the moment of the interview.

Limitations

Interviews were collected in person and online. During the first phase from spring to summer 2022, most of the main research team was in the countries of study, which made it possible to not only conduct in-person interviews but also to collect personal observations. Thereafter most of the interviews were conducted online. In total, we conducted 50 in-depth interviews with people who left Russia after February 24, 2022.

The research team itself is part of the group that is the focus of this research. This is both a limitation and an advantage. On the one hand, the emic approach makes it possible to see beyond the superficial picture of emigration and delve into the details. We went through the same stages ourselves, faced similar problems as our respondents, and could observe the life of emigrants from the inside. On the other hand, this lack of distance can narrow the research perspective. Therefore, throughout the course of this study, we consulted with colleagues from outside the migrants’ group and tried to cover the external perspectives as well.

Another limitation of this study was the lack of funding until the final stage. This project was initially implemented voluntarily. Because of this, we did not distribute the questionnaire through a wide array of different channels but used those available to us, namely Telegram and Facebook. Still, we believe that this method of selecting respondents will not result in dramatic distortions of the research material. Our own experience has led us to conclude that practically all migrants use such channels, on which almost the entire social infrastructure for communication within the migrant community is based. This research is now supported by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Professional sphere and plans

In this section we define and describe the main groups of newly arrived people to provide a basis for the subsequent analysis of their economic decisions. Data in this section was obtained from the quantitative survey.

Socio-economic features and professional sphere

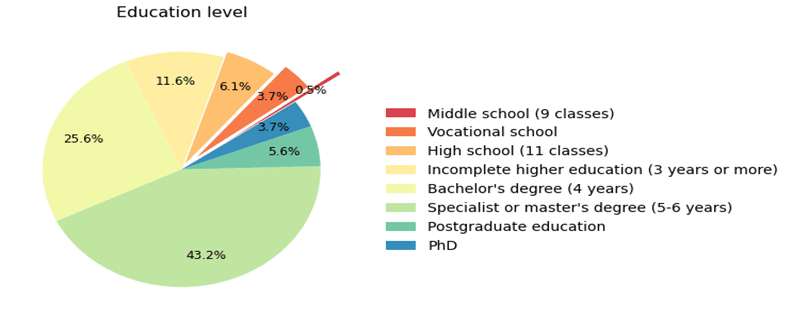

The survey shows that most of our respondents are young people: 59% were born in the 1990s. They are predominantly from big cities; more than half moved from Moscow and St. Petersburg. Our data shows that most of our respondents, 78.1%, have higher education (bachelor’s degree, specialist or master’s degree, postgraduate education, and Ph.D., Fig. 1). This corresponds with data from another survey conducted among 2022 Russian migrants— in and beyond the South Caucasus region— that showed rates of higher education close to our results, 81% (Kamalov et al. 2022). These results are a stark contrast to the 31% of people with higher education among 25-64-year-old workers in Russia (Distribution 2018).

Figure 1

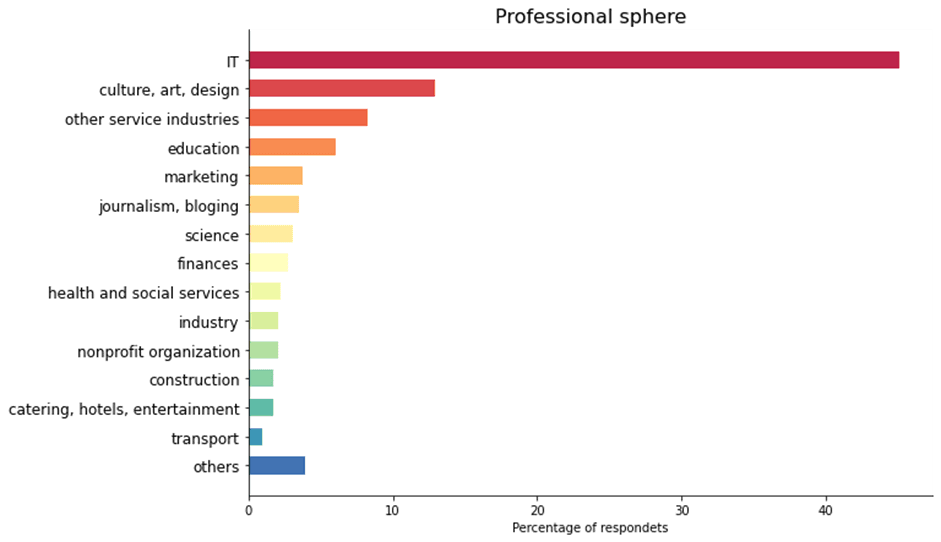

In terms of profession, almost half of our respondents are highly skilled IT specialists (Fig. 2). A significant number of artists, researchers or teachers, journalists, etc. are present in this group as well. This substantial number of highly-skilled professionals might factor into explanations of why there is a significant amount of migrant entrepreneurship as a ‘transnational practice’ which also leads to diasporic development (Zhou and Liu 2017).

Figure 2

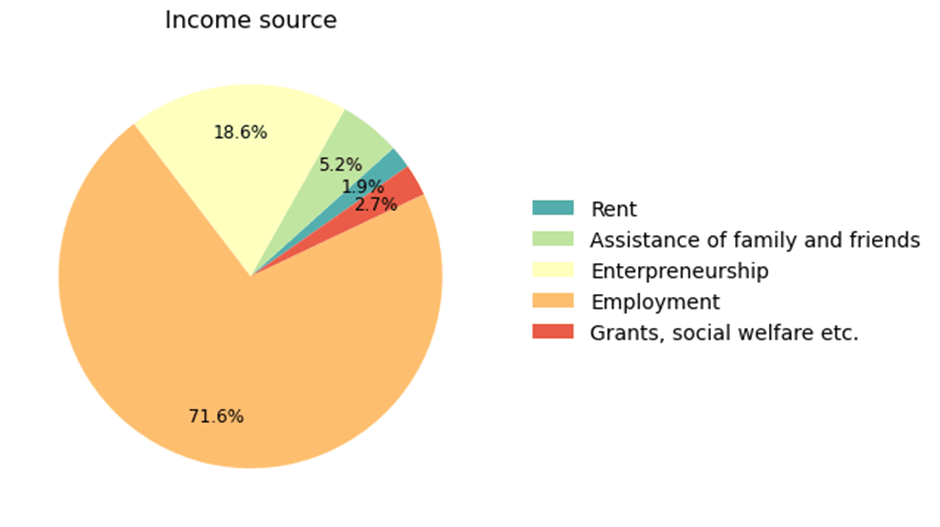

Our respondents predominantly acquire their income through employment (Fig. 3). Another significant source is entrepreneurship (18.6%).

Figure 3

Respondent’s expectations and plans

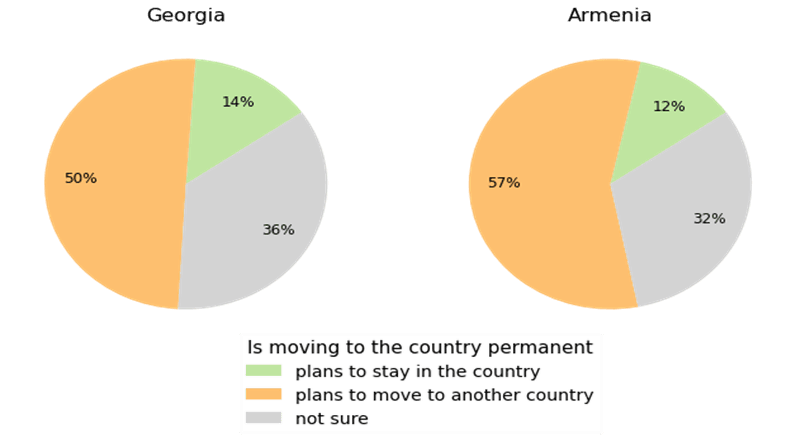

In terms of plans for the future, most of the respondents did not have specific plans. When asked if their move to their new location was permanent, more than one-third answered that they were ‘not sure’, expressing uncertainty for such a fundamental life decision. This reported degree of uncertainty is likely due to the timing of our survey. It was conducted in the spring of 2022 when the respondents had just arrived, as their previous life plans had just been upended by the unexpected migration. Responding to the question “Was your current departure from the country planned or spontaneous?” 51% answered ‘spontaneous’ and 35% ‘rather spontaneous.’ It is quite possible the situation undermined the respondents’ capability for long-term life planning.

Figure 4

Those who plan to stay in the South Caucasus are a minority (14% in Georgia and 12% in Armenia, Fig. 4). Other questions, which concerned the possible duration of the stay in Armenia or Georgia, showed that migrants plan only short-term, from a few weeks up to a few months. About 25% in Georgia and 10% in Armenia intend to stay there a year or more. More than half of the respondents have plans to move to another country, and only a small percentage intend to return to Russia. Only three percent reported a desire to return to Russia and consider it possible, while 17% want to return and consider it possible, but with a low probability. From this line of interview questioning, we additionally identified an interesting group for further analysis: ‘returnees,’ those who returned to Russia at the end of the summer of 2022. According to our team’s observations, part of this group left again to escape mobilization in the autumn.

Migration created a context characterized by employment uncertainties and the difficulties of living with only short-term plans. Uncertainty about the future affects planning horizons and interrupts the continuity of labor biographies. The ending of a familiar world in which it is possible to make long-term plans is an experience shared by almost all of our interviewees. However, long-term uncertainty has been difficult. Therefore, most respondents at some point start to expand their plans, sometimes covering periods of six months, a year, or even several years, and yet they treat such plans as something ephemeral that can break down at any moment due to the changing socio-political situation.

Economic strategy

Data in this section was obtained from our interviews.

Professional strategies built up before the war have been severely transformed by spontaneous migration. The absence of long-term and well-established plans is typical for most migrants (Brednikova 2020) and the sudden decision to migrate after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, especially after the start of the Russian military mobilization, has resulted in more chaos. Here, we briefly discuss the typical and outlying employment strategies described by our interviewees. We mainly focus on the preservation of a previous income and job, searching for a new job in the same professional field, changing profession, and opening or relocating business.

Preservation of a previous income. A considerable number of our respondents have continued to work at their jobs in Russia remotely and therefore have not entirely integrated into the host countries’ employment sphere. Many already have had experience of working remotely from Cyprus, Bali, and other touristic places that are popular among lifestyle migrants. According to our observation, migrants working remotely continue getting payments in rubles or foreign currency (dollars or euros) or switch to cryptocurrencies.

However, starting from February 2022, a series of problems began to arise for employers and freelancers in Russia: blocking of Russian bank cards, the inability to use accounts in professional software, discrimination from foreign partners based on the citizenship of workers, etc. For example, some respondents talked about instances when Russian freelance screenwriters were refused of a job opportunity because of their citizenship.

Another strategy to keep a previous job is a relocation organized by a company. This presupposes some degree of integration due to the offline office, a salary in a local currency, etc. The phenomenon of relocating offices is considered to be a feature transnationalism (Boccagni 2022).

I was working as an IT specialist in a global international company, there were approximately 15 offices in Russia and they are closed… The alternative is to join a local office in the country where we moved. The company has offices in Armenia. It was not only Armenia, other countries too, but there was also the so-called program of ‘fast relocation’, and there was a list of countries including Armenia (male, approx. 55, Armenia).

Another strategy to keep the same source of income is relocating one’s own business. Since 2022, the number of Russian companies registered in Georgia has increased significantly; from March to June 2022, 6,400 Russian companies were registered in Georgia, which is several times more than the number registered in the whole of 2021 (Transparency 2022). At the same time, we observe that official statistics on employment and transit emigration (leaving Armenia or Georgia after receiving a visa for a third country) are often not only inaccurate but also poorly maintained or inaccessible by the public. One of our interviews provided an example of how these statistics may not cover specific cases. An owner of a small start-up moved all its employees to Armenia, hired a local accountant, but then moved to Georgia due to its more attractive business regulations. Moreover, according to our observations, many IT specialists who decided to stay in Armenia or Georgia for at least several years opened their entrepreneurship here (and closed their self-employed status in Russia). Along with IT, other businesses are also re-opening in the educational and humanitarian fields, i.e. language courses, tutoring, translation, editing, video production, etc.

Searching for a new job in the same professional field. Some of our respondents managed to find a job in their professional field in the receiving countries. One of our interviewees who lost her job after an international company left Russia, found a job in an IT company in Yerevan after emigrating. She attended several job interviews at Armenian companies but found a position in a Russian company that opened an office in Yerevan (female, approx.. 30, Armenia). Another example of effective employment that appeared in our interviews is the case of a microbiologist who was head of a laboratory at a Russian university. As a ‘veteran’ political activist, she has a broad social network. She asked for help from one of Russia’s political NGOs. The NGO team sent her to Armenia and instructed her on the specificities of the local medical job market. She found her knowledge to be in great demand in Yerevan medical labs, and so even had an opportunity to choose between different employers. Thus, we see a combination of different factors that helped her to find a job in her professional field, including unique and highly demanded professional skills and an extensive network built over years of political activism.

A special cases of keeping the field but changing position is minority entrepreneurship, which we define as opening a small, often semi-official business for migrant clients and migrant workers. This is a case of migrant infrastructure (Zhou and Liu 2017). For example, a few schools for Russian-speaking children were opened in Yerevan in 2022. Another popular field is gastronomy and cafes, for example, the case of sushi delivery in Dilijan. Japanese cuisine is very popular among Russians but not established in Armenia, and the lack of sushi was often mentioned in conversations and chats. This semi-official business appeared and it predominantly advertised its work in a migrant chat. Online communication provides migrants with information related to rent, jobs, taxes, and bank accounts, and other necessary topics in a new country, based on the experience of migrants who arrived earlier.

According to our observation, the typical cases are tutoring for migrants (chess, Russian literature, music) and sports and leisure activities (yoga, pilates, English speaking clubs, reading clubs, concerts, excursions with children, etc.). Some such activities were initially free of charge or for donation, or charged prices to cover the rent of a café or coworking space. Later, some of these activities started to bring income to organizers who were ready to invest their time in ‘homemaking’ practices. All the cases we observed were varying in form; some were a organizations, initiatives for friends with the same interest or position, i.e. people with children, and a business. Many of them are related to the mothers’ practices (developmental activities) and lead to the monetization of ‘homemaking’ for women without permanent income and the circulation of money within the migrants’ community.

More official cases are the numerous bars and restaurants in Tbilisi and Yerevan that, in theory, are open to all customers but are patronized de facto mostly by Russian migrants or tourists. It should be mentioned that there is no strong border between migrant entrepreneurship businesses that serve the diasporic ethnic enclave and those that have an established customer base in the host community, as in the case of a new Russian-owned hair salon in Tbilisi with primarily Georgian clients.

People with offline jobs, for example, nail-art masters and hairdressers, can easily find a new job, albeit sometimes with changes in income and number of clients. This strategy presupposes more integrated relationships with a host community, both with customers and employers. Thus, it creates space for these central contemporary migration practices: homemaking, transnational practice, and lifestyle migration. Our participant observations in a relatively small town, Dilijan (Armenia) found three new Russian emigrant doctors in the local medical centre (an endocrinologist, who arrived in spring, 2022, and a neurologist and pediatrician, after the mobilization in September). Another case is a person who had two professions, industrial mountaineering and wooden furniture production. In Georgia, he works as a woodworker in a Georgian-owned carpentry workshopA typical feature of varying businesses or employment patterns is that a person often has a few professions or abilities, for example, cooking sushi and tattooing. In Russia, some of these skills may have been secondary, not the main source of an individual’s income. In a new setting, individuals with multiple abilities can comparatively effortlessly utilize one or two of these secondary skills.

Changing the profession. It should be noted that our division between “keeping” and “changing” is a constructed notion that we define in line with our respondents’ understanding of it. Some people consider their new work after emigration as changing the field, even though it was relatively close. For example, one respondent worked as a DJ and bartender in clubs in Russia but in Georgia, he found only the position of waiter. Assessing the possibility of keeping the same professional field is a part of personal expectations, as in the passage below:

([sitting in the plane] I did not understand at all where I was flying, why did I leave my home? And I began to think what can I do. I have worked in the hotel industry for so many years but no matter how specialized I am and no matter my experience, I will definitely not get a job here with a Russian passport. And when I flew away I still worked on the hotels’ network but I was well aware the management did not support the move and the remote work format in any way. I started thinking about what to do. (male, 26, Georgia)

He decided to search for a new field and opened a coworking space in Tbilisi.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable examples among our respondents that illustrated radical change in professional trajectory was the transition of a cardiovascular surgeon to the IT sphere, learning Python programming language. This requires a great deal of stamina, much more than many have after the stress of the emergency departure. Therefore, many respondents described themselves as being in ‘transit,’ in the space between the past and the future. According to our respondents, it is also possible to find oneself in professions associated with a broken career:

I studied at the university and planned to work in my specialization: sociology/anthropology, maybe to go to the master’s program and then into applied research. I had to leave the university and start working remotely in sales, b2b wholesale of medical equipment. And study web development at the same time. (female, approx. 23, Georgia).

The decision to change the sphere of employment and start a new career can be very difficult. These interviews reflect the emotional weight of the new circumstances on the migrants. It is important to note that a number of respondents described the change as both more or less temporary employment (as in the previous passage) and as a radical innovation, as in the quote below:

It became clear to me that everything was destroyed when the war began. For seven years I built my career at the academy, defended my Ph.D., established international contacts with colleagues from Europe and China, and sought publications in international journals. All this was destroyed at the start of the war… I decided to leave the academy and try to find a job in IT — sounds like a cliche, yes, but today it is the only reliable way not to live in poverty in exile. I figured that I have about a year, and by the winter I will need to already have the skills and work in a new field. I chose data analytics because I had experience in social research, including part-time jobs in the commercial field. I paid for the course and began to study. I spent the whole spring and summer studying, and by the end of the summer I began to go on interviews… After the start of mobilization, I went abroad, as planned, just a little earlier (originally planned for December-February). Now I am building my life here, I work in an IT startup. (male, approx. 35, Georgia).

A plan to move in the winter changed after the mobilization, and the respondent preferred to discuss it as recovering a normal status and creating a new life. It is his claim for agency and personal control over his life. This is reflected in his agentive constructions (I paid… I began… I went abroad…) as opposed to his passive constrictions describing the war (was destroyed) and in the detailed description of his choice and his plan. The different ways of speaking about plans show how people try to rebuild their lives and find a ‘script’ for understanding them.

Until now the labor market in Russia was characterized by relatively low professional mobility – a radical change in the type and nature of professional activity was an exception (Gimpelson, Kapeliushnikov 2017). Yet among our emigrant respondents, we observed an active search for new labor activities, including attempts to generate income through hobbies or other abilities. New professional spheres were sometimes related to a respondents’ previous interests. For example, one of our interviewees who recently moved to Georgia opened a podcast studio and additionally participates in tourism projects because he previously worked in the tourist industry (male, 26, Georgia). Another such case is a respondent who having experience in alpinism, in Armenia found a job in construction.

For many years I was a freelancer working on different projects as a rope access technician, mountain guide, and field sociologist. I have brought my means of production to Yerevan, i.e. my rope equipment and laptop (male 30, Armenia).

Sometimes this includes pursuing what they wanted to do in their previous life. Some migrants try to realize new opportunities in their new location such as starting a new job, creating a new social circle, acquiring a new lifestyle, and finding new hobbies, approaching this with the mindset, “If not now, when?”

Conclusion

Migrants from Russia are heterogeneous in terms of their professional and job status. We define three main employment strategies: preservation of a previous income and job (including relocating the business), searching for a new job in the same professional field, and changing profession. Our survey showed that many respondents are connected to the IT sphere and have remote work arrangements, so they can easily continue to work at their jobs at distance, or their companies relocated from Russia to avoid sanctions and provided staff the opportunity to move to Armenia or Georgia. The position of people with a remote job is partly close to lifestyle migrants or digital nomads, and that of the staff of a relocated company is close to privileged labor migrants. Other people choose between re-training to change their sphere of work and a new job in the same sphere. The newly arrived migrants create a “comfort zone of online forums” (Lawson 2016) where they can communicate with each other in Russian. They participate in different chats, forums, and groups in messengers, and online communication provides them with a support network that is crucial for their integration process. Additionally, the internet has become a place of economic activism within the migrant community, with newcomers creating infrastructure to support each other. The people we talked to about their lives and work included stories about how they interacted with others who had moved to the area. They often started businesses that catered to other migrants, creating a small community that didn’t include people originally from the area. Migrants also tended to gather at certain places, like bars, schools, and sites of leisure activities, that reminded them of their lives before they moved, which can be viewed as ‘homemaking.’ This made them feel more at home and even helped them in employment like teaching in their native language, creating coworking spaces, or opening sushi restaurants. They were able to make money from these activities through connections with other migrants who had jobs (‘digital nomads’ with remote work, or people from relocated companies).

Interviews illustrated the gap between the necessity to plan the future and experiencing the impossibility of doing this planning in the current realities. There are also unexpected ‘script-breaking’ effects. In the context of the collapse of the previous life, some people change their life plans dramatically and embracing the uncertainty. Another type of uncertainty surrounds their new status. One assumption that would require more research is thatthe reluctance to take on the new status is due the sense of the temporality of the new situation – whether to stay in the current place of residence, leave for another country, or return to Russia. Another factor is the expectation that migration implies adaptation to a new situation and the search for new life strategies, which, as we found out can sometimes include doing what they have wanted to do for a long time.

*We express gratitude to the Ebert Foundation (Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung) for their support in providing resources for processing interviews and translating materials. We are deeply grateful to other members of our team, first of all, Gleb Stukalin, who read the draft, and Timofey Chernov, Boris Grozovsky, Daria Kuznetsova, and Egor Sokolov, as well as the journal’s reviewers, Vadim Romashov and Sergey Rumyantsev, for their valuable comments.

References

Avetisyan, Ani, Shoshiashvili, Tata. 2022. Evictions surge as rents skyrocket in Yerevan and Tbilisi. OC Media. 17 March 2022. https://oc-media.org/features/evictions-surge-as-rents-skyrocket-in-yerevan-and-tbilisi/

Benson, Michaela, and O’Reilly, Karen. 2016. “From lifestyle migration to lifestyle in migration: Categories, concepts and ways of thinking.” Migration studies, 4(1), 20–37.

Bessudnov Alexey, Shcherbak Andrey. 2020. Ethnic Discrimination in Multi-ethnic Societies: Evidence from Russia. European Sociological Review, 36(1), 104–120.

Boccagni, Paolo. 2022. Transnationalism and homemaking. In: B. Yeoh, F. Collins (eds.), Handbook on transnationalism, Edward Elgar.

Brednikova, Olga. 2020. Mobil’naja zanjatost’ mobil’nogo subjekta [Mobile employment of the mobile subject]. The Journal of Social Policy Studies, 18(4), 705-720.

Distribution 2018. Distribution of 25-64-year-old population in Russia in 2018, by the highest level of education attained https://www.statista.com/statistics/1237744/educational-attainment-russia/

Gimpelson, Vladimir, Kapeliushnikov, Rostislav (ed). 2017. Mobil’nost’ i stabil’nost’ na rossijskom rynke truda. [Mobility and Stability in the Russian Labour Market]. Москва: НИУ ВШЭ.

Hack-Polay, Dieu. 2019. Migrant enclaves: disempowering economic ghettos or sanctuaries of opportunities for migrants? A double lens dialectic analysis. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy. 13(4). 418-437.

Honorati, Maddalena, Bartl, Esther Maria. 2021. International Migration from Armenia and Georgia (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/604591625240160008/International-Migration-from-Armenia-and-Georgia

Lauster, Nathanael, Zhao, Jing. 2017. Labor migration and the missing work of homemaking. Social Problems, 64(4), 497–512.

Kamalov, Emil, Kostenko, Veronika, Sergeeva, Ivetta, Zavadskaya, Margarita. 2022. Russia’s 2022 Anti-War Exodus. The attitudes and expectations of Russian migrants. PONARS Eurasia. September 6, 2022.

Korpela, Mari. 2010. Me, Myself and I: Western Lifestyle Migrants in Search of Themselves in Varanasi, India. Recreation and Society in Africa, Asia and Latin America. 1(1). 53–73.

Lawson, Michelle. 2016. Identity, Ideology and Positioning in Discourses of Lifestyle Migration: The British in the Ariège. Palgrave Macmillan

Massey, Douglas, 2012. Reflections on the dimensions of segregation. Social Forces 91 (1), 39–43, 2012.

Massey, Douglas, Denton, Nancy. 1988. The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces 67 (2), 281–315.

Portes, Alejandro, 1987. The social origins of the Cuban enclave economy of Miami. Sociological Perspective. (4), 340–372.

Preibisch, Kerry, Grez Evelyn E. 2013. Between hearts and pockets: locating the outcomes of transnational homemaking practices among Mexican women in Canada’s temporary migration programmes, Citizenship Studies, 17 (6-7), 785-802.

Repetti, Marion, Phillipson, Christopher, & Calasanti, Toni. 2018. Retirement Migration in Europe: A Choice for a Better Life? Sociological Research Online, 23(4), 780–794.

Sahadeo, Jeff. 2012. Soviet “Blacks” and Place Making in Leningrad and Moscow. Slavic Review. 71(2), 331–358.

Transparency 2022. Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia: Impact of the Russia-Ukraine war. Transparency International: Georgia. 3 August 2022. https://transparency.ge/en/post/georgias-economic-dependence-russia-impact-russia-ukraine-war

Zhou, Min, Liu, Hong. 2017. Immigrant Entrepreneurship and diasporic development: the case of new Chinese migrants in the USA. In: Zhou, M. (Ed.), Contemporary Chinese Diasporas. Palgrave Macmillan. 403–423.