More than three decades after the Soviet collapse, the Armenia–Azerbaijan conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh has entered a new phase. Following Azerbaijan’s military victory in 2020 and the displacement of Karabakh’s Armenian population in 2023, the territorial dispute that defined the region for a generation appears relegated to history. Yet a deeper challenge persists: the reimagining of national identities in Armenia and Azerbaijan, still structured around mutual enmity.

This antagonism is not ancient or immutable. The first recorded violence between these two peoples dates back only a century. Rather, it is the product of recent national identity formation, a recursive process in which each society has defined itself in opposition to the other. What began in the late 1980s as a dispute over administrative status escalated into ethnic cleansing, mass displacement, and two wars, becoming foundational to the post-Soviet state-building projects of both republics.

Karabakh became a crucible in which national identities were forged. In Armenia, its defense was cast as a continuation of survival against Turkic and Islamic colonizers. In Azerbaijan, the loss of Karabakh and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis were framed as a national humiliation, linked to a broader historical injustice in which Christian imperial powers were seen as privileging Armenians of the region.

These narratives became embedded in state institutions, school curricula, monuments, media, and cultural production. As political scientist Michael Billig would describe, this was banal nationalism in action: the everyday reproduction of identity as enmity. Over time, the image of the other as a permanent threat became central to how each society imagined itself.

This recursive identity-building created a feedback loop: each side’s self-image sustained the conflict, prompting the other to reciprocate. Peace became not just politically difficult but ontologically unthinkable. According to ontological security theory, societies, like individuals, require a coherent sense of self. For Armenia and Azerbaijan, the conflict provided that consistency, offering the states legitimacy, cohesion, and direction.

The 2020 war and the 2023 displacement of Armenians from Karabakh may have dissolved the territorial core of the conflict, but not its identity foundations. In Azerbaijan, the military victory ushered in ontological affirmation. A long-standing self-image of victimhood gave way to one of restoration and ambition, expressed through rapid reconstruction in Shusha, triumphant rhetoric, and regional aspirations. Yet the discourse of enmity persists, now expanding through the “Western Azerbaijan” narrative, a move that risks reinscribing competitive spatial imaginaries when de-escalation is urgently needed.

In Armenia, the defeat triggered an ontological crisis. For three decades, defending Karabakh was not merely policy, it was a source of national pride and a linchpin of statehood. In the aftermath, identity fragmentation emerged. Some opposition groups embrace revanchism. Prime Minister Pashinyan and his allies, by contrast, advocate for a “Real Armenia,” reimagined as a democratic state within its internationally recognized borders. Yet this shift remains fragile, marked by the Prime Minister’s own rhetorical pivot, from only recently proclaiming “Artsakh (Karabakh) is Armenia, period!” to now asserting that Armenia is stronger for having “freed itself” from it.

This postwar asymmetry, Azerbaijan’s ontological confidence versus Armenia’s fragmentation, has disrupted the old equilibrium. But the deeper structures of enmity remain intact. Education systems still transmit exclusive histories; public memory valorizes heroism and sacrifice; media continue to amplify grievance. Nationalist elites, including those in civil society and the intelligentsia, have largely resisted this transformation. The scaffolding of rivalry has not been dismantled, only adjusted to new conditions.

This moment of disruption offers both peril and possibility. On the one hand, rupture can create openings for transformation. Younger generations in both countries, exposed to globalized media and fatigued by militarized nationalism, are tentatively articulating alternative visions. The emotional monopoly of enmity may be loosening, but these shifts are both fragile and uneven.

On the other hand, the collapse of old narratives can leave a vacuum for radicalization. Identity anxiety, especially when unaddressed, can draw societies back to antagonism. The absence of war does not guarantee peace, especially when the infrastructures of rivalry endure.

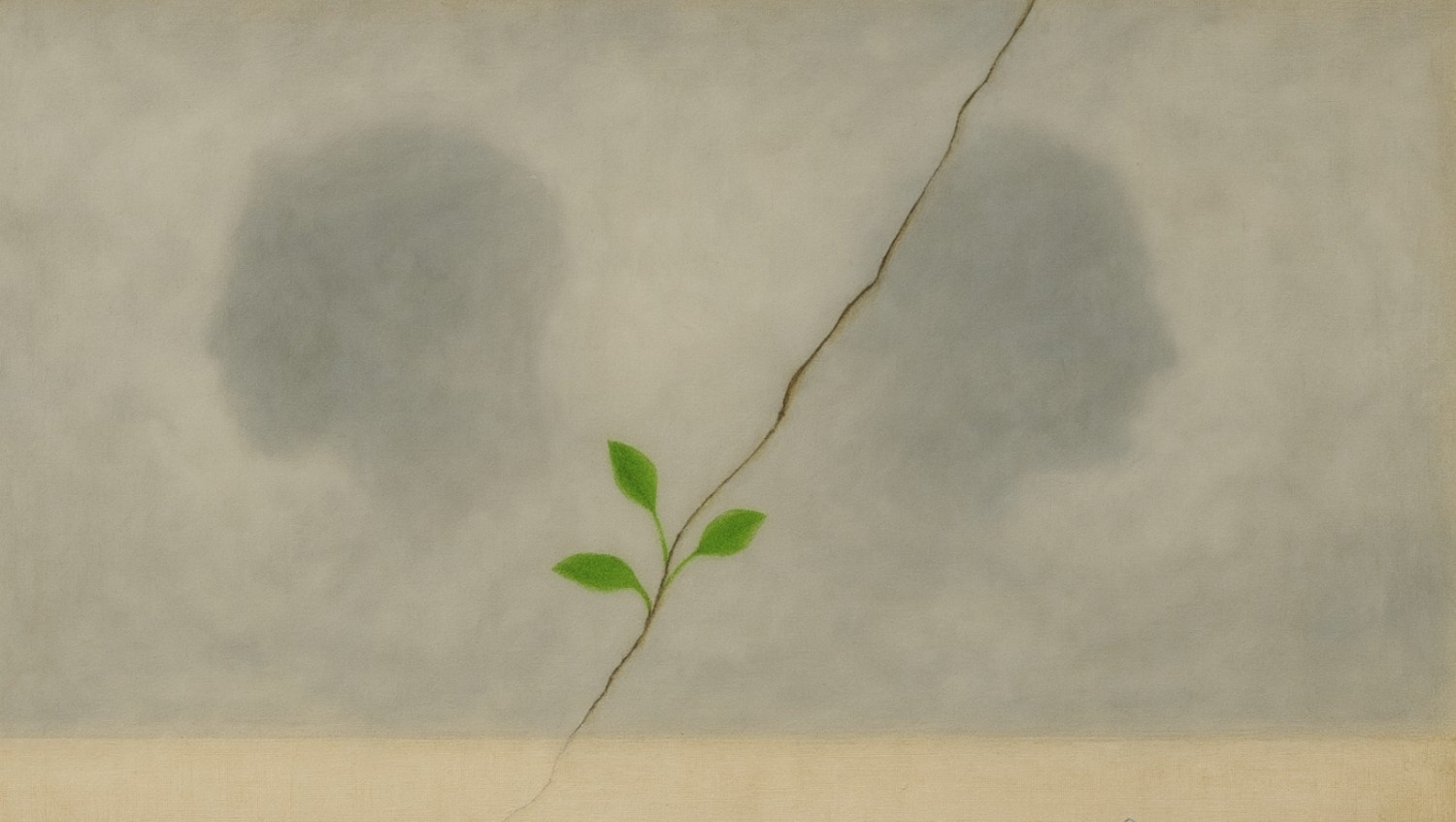

The soil for change may be fertile, but spring will not bloom without care. It must be cultivated through sustained efforts to reshape the foundations of national identity. This means revising the infrastructure that has long served conflict — school curricula, cultural production, and political discourse — to foster pluralism and critical reflection. It means creating educational and media spaces that humanize the other, without erasing trauma or falling into false equivalency.

It also requires confronting the political economy of identity reproduction. For decades, political, economic, and cultural elites have benefited from sustaining the rivalry. New incentive structures must reward bridge-builders instead of grievance entrepreneurs.

If the current inertia hardens into a new status quo, the region risks returning to cycles of violence, not because Karabakh remains contested, but because identity remains bound to enmity. The task now is not only to negotiate future borders, but to reimagine the foundations of identity itself.

Recommendations for Governments, Donors, and Civil Society

These recommendations emerged from a series of 2025 workshops with local and international experts on post-conflict transitions. The aim was to develop strategies to facilitate the transition of the region from conflict to a post-conflict phase and prevent a slide towards renewed violence. Strategic, long-term engagement with identity infrastructures is essential.

To Governments:

Nation-building is neither an organic nor spontaneous process. Government intervention, hence, becomes indispensable in shaping the symbolic, institutional, and discursive architectures of national identity. We recommend:

- Create platforms for intellectual engagement that reframe national identities within a post-conflict lens.

- Publicly articulate inclusive post-conflict national visions that engage diverse perspectives.

- Promote civic forms of nationalism untethered from colonial-imposed rivalries.

To Donors:

With most regional expertise still focused on managing active conflicts, it is critical at this stage to support capacity building and the retraining of civil society actors to work within a post-conflict logic. Priorities should include:

- Support educational programs on peacebuilding, trauma healing, and reconciliation.

- Invest in media and cultural initiatives that promote coexistence and deconstruct enmity-based narratives.

- Fund scholarly and expert engagement on identity transformation and post-conflict transitions.

To the Academic and Civil Society Sectors:

In post-conflict societies, academic and civil society actors play a crucial role in shaping how national identity is understood and reimagined. They can act as epistemic mediators, capable of bridging polarized publics and generating knowledge that is both critically reflective and socially transformative. Some directions to explore include:

- Study and adapt comparative post-conflict experiences to the South Caucasus.

- Revisit early 20th-century identity debates to envision plural national trajectories.

- Develop fiction and media that imagine Armenia and Azerbaijan free of conflict and rooted in civic belonging.

- Institutionalize scholarly spaces to interrogate the nexus of identity and transition.

- Make identity debates accessible and inclusive through public deliberation.

- Promote cultural productions - books, films, comedy, educational content that deconstruct conflict narratives and animate new imaginaries.

The road ahead is not only about political settlements. It is about redefining how societies imagine themselves and each other.