This was meant to be another story about the importance of preserving history, even when it hurts. It was supposed to focus on Firdusi—or “Firdus” as the local Armenians call it—an old neighborhood in the heart of Yerevan, now on the verge of disappearing and being replaced by a new area named District 33. But instead, it has turned into a different story: one about how our memories can be shaped by a shifting political landscape. Two voices will help to approach this story and view it from a researcher's point of view and an artist's.

Background

When Armenians fled the massacres in the Armenian-inhabited cities of the Ottoman Empire (in what is now eastern Turkey), many resettled in specific areas of Yerevan. One of those areas was Firdus.

The Firdus neighborhood was always viewed as a “ghetto,” despite being located in the heart of the city. It had its own unique atmosphere, distinct from the nearby city center just a few steps away. Always welcoming to strangers and migrants, who brought with them memories and ideas of urban architecture, Firdus both felt and looked different. In this diverse community, people coexisted peacefully, where ethnicity mattered less than simply being “from Firdus.”

In the 80s and 90s, this area became known for its cheap market, where people could buy the most affordable food and clothing. Many millennials remember purchasing their jeans and other clothes here, where instead of a dressing room, there was only an old shower curtain, a small fitting mirror, and a piece of cardboard on the floor to avoid standing barefoot on the cold ground. Those years are gone, but the memories of poverty and the shame it carried left a lasting mark on this area.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons people struggled to see the other side of Firdus and recognize its historical significance and architectural value to the city.

Firdus:Values

“Attention helps to create or shape values. Unfortunately, places connected to traumatic experiences for society often receive less attention and disappear from public spaces more easily. Firdus is one of those places, unlucky enough to be associated with negative images from the past, such as poverty," says Tigran Amiryan, head of the "Cultural & Social Narratives Laboratory" (CNS Lab). Amiryan, a young professor, has led several projects documenting urban memories.

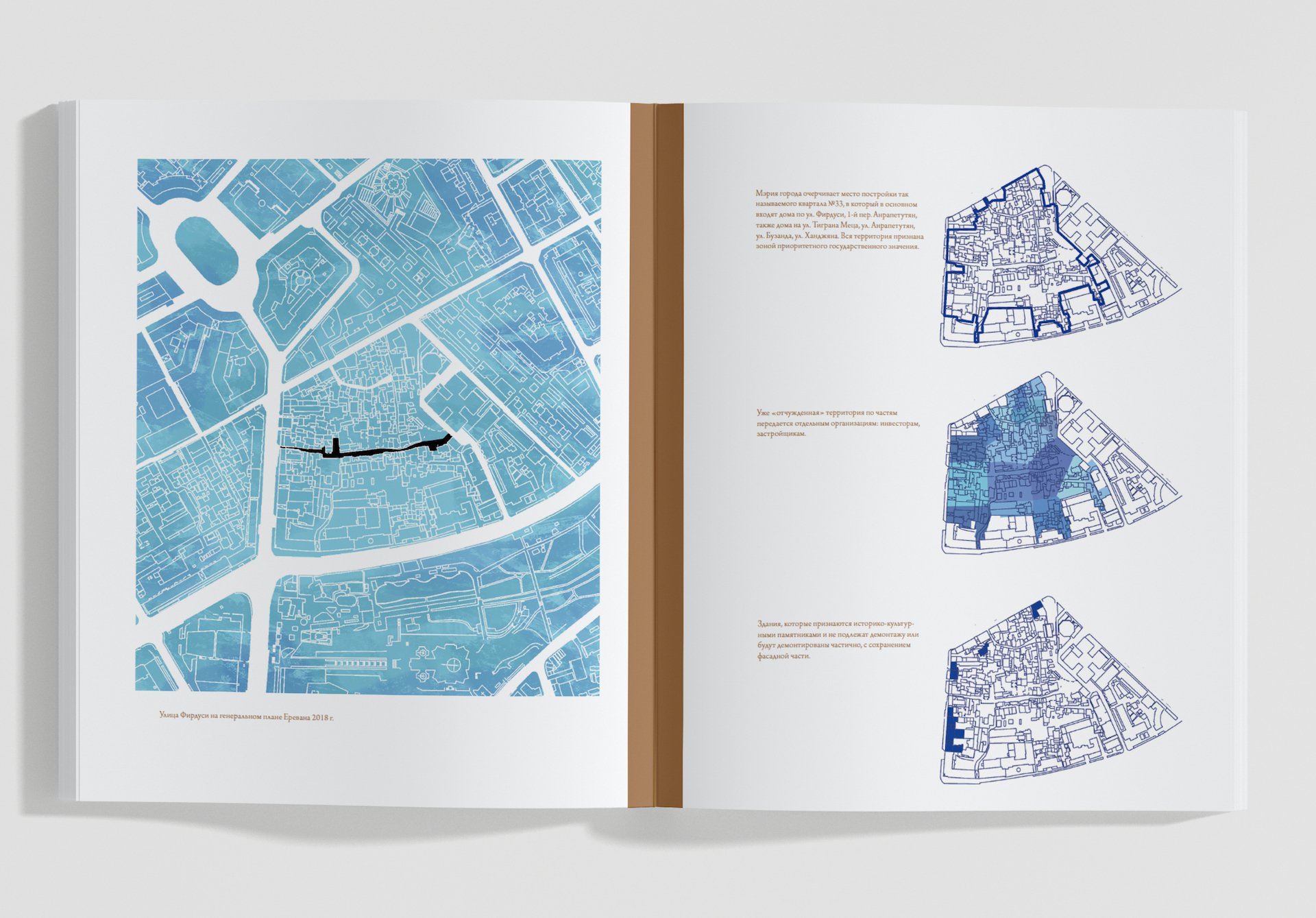

He began researching public memories in 2018, using that data to curate a series of books. Memory of Firdus is one of the books created by him and his lab.

Tigran explains that, from an architectural perspective, Firdus was a unique example of vernacular architecture—an architecture created by ordinary people, born from their memories of urban spaces. "It wasn't a state-driven, ideologically polished architecture, but a space shaped by people who migrated and recreated their memories of home. Some houses had balconies, others had large basements, small gardens, distinctive facades—features that reflected what they remembered from the places they had left behind. Migrants imprinted these urban memories into a new space, allowing for diversity in the growing city. Despite being located in the very center, near Republic Square, Firdus remained remarkably untouched by change and maintained a close-knit community. In Armenian, they called themselves 'Firdustsi' (people from Firdus). Every family in the area had fascinating memories. It was like a 'net memory,' where stories were interwoven. When one person forgot part of their story, another—often a simple neighbor—would fill in the gap, because they were all part of each other's lives. It’s an exceptional example of collective memory, and a unique experience of peaceful coexistence, where stories intertwined just like the houses and gardens of Firdus," says Tigran.

The other part of the negative image this area started to have, according to Tigran, is the

fact that it was inhabited by diverse cultures, some of which gained more spotlight after Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict.

"I believe the idea propagated by the USSR—that each country must be purely inhabited by its native people—significantly contributed to the trauma in society," Tigran shares. "Specifically, between 1940 and 1952, Stalin's decision to relocate all Azerbaijanis from Armenia to work in the cotton fields of the Kura-Arax lowland left a deep wound in public memory. They were offered 1,000 roubles for relocation and promised housing in exchange. Naturally, many families accepted the offer, and the relocation process began. However, this process later transformed in public memory, merging with the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict and suggesting that those Azerbaijani families left because of the conflict, which wasn't the case.

We had a fascinating experience ourselves, witnessing how the memories of the people we interviewed were influenced by propaganda,"

Tigran continues, giving a bit wider view on the diversity of this neighborhood "Persians, Jews, Greeks lived there too. Diversity in growing cities is a normal occurrence; it’s the Soviet idea of a 'pure nation' inhabiting their 'ancestral homelands' that has created many misconceptions we still need to reinterpret." says Tigran.

Firdus: Power of Memory

"We often erase memories from our past to protect our future from 'mistakes,' but hiding the past does not help; in fact, it creates a dangerous foundation for misconceptions," says Angela Hovakimyan, an emerging artist who rented a studio in Firdus area for the last 3 years.

"We always hope that our future will be more curated and clean if we simply destroy everything we don't like. But public spaces hold memories too; you can demolish buildings, but you cannot erase the memories they contain, nor can you forget the people who still remember those spaces," she continues, guiding me through the neighborhood that looks abandoned and almost ready to fade into history. Angela walks perfectly knowing that soon it will be her time to leave this space too.

Today, the area is mostly uninhabited, and everyone who once believed in stopping the redevelopment process has left. Only a few have remained.

Angela shares a connection with Firdus long before renting a space here. Her first artistic interaction with this space was through the street art project "Ctrl-Shift Save," a playful call to save the neighborhood.

“My concept was simply to remind people to save our past because sometimes even the most obvious things need to be emphasized,” says Angela. “I had no idea that one day I would end up renting this space and spending most of my time here, painting or planning exhibitions. It was a coincidence, but who knows—maybe it was fate.”

She did a little pause to answer an email and then continued:

“I think I have always been attentive to the old buildings and districts that are still preserved because I was raised with a fear of losing my past and my connection to familiar things. I was a child, but I remember how my grandma suffered the loss of her native village, Nakhchevan. She never fully recovered from that loss. And when I say 'loss,' I know that Nakhchevan still exists on the map. Places don't vanish, but the connection to them does. Logically, you understand that, but the human mind and emotions don't always work that way.”

She adds, “When I created my first street art piece here, someone added a message to it: ‘The past is beautiful.’”

The art studio that hosted Angela and many other artists in Firdus ceased to exist on January 4th. Demolished by the construction company there's only one wall left from it.

Despite much of the neighborhood lying in ruins, up to five families remain, refusing to leave their homes. One of the residents even started investing in their home by adding solar panels to their roof.

As these families and individuals in the Firdusi neighborhood continue to fight for their rights, society has been granted an opportunity to pay a final visit and bid farewell to the area and the memories it holds for each of us.

These people offered us a brief pause before the inevitable—a future where Firdus will become the 33rd district of Yerevan, a place we will no longer have access to.

Photo credits:

Images of the book "Firdus: The Memory of a Place" collective monograph ed. by T. Amiryan, S. Kalantaryan , CSN lab, Yerevan,2019.

book cover and illustration by Harutyun Toumaghyan

Demolishment of Firdus, Jan 4 photographed by Marine Melkonyan