It’s September 27th. The afternoon sun spreads over the city, filled with silence. In a city where cleanliness was once a point of pride, streets are now full of abandoned belongings covered with dust. Seventeen-year-old Beniamin Hayrapetyan is waiting for one of the last buses to evacuate to Armenia. In the city, he noticed Azerbaijani police cars driving around.

“Our capital (Stepanakert) has turned orange. All the traffic lights had this color and didn’t change. Orange painted the canvas of our waiting.”

After more than a 9-month blockade, Azerbaijan launched an attack on Nagorno Karabakh, starting a war that lasted a day. More than 27,000 children under 18 have been forced to leave their homes. Among them are Benjamin Hayrapetyan, born in the village of Sarushen (the region of Askeran), and Nushik Mirzoyan from Kolkhozashen (the region of Martuni, known as Khojavand in Azerbaijan).

Benjamin now lives in a hotel near Sevan, 65 km northeast of the capital Yerevan. In the room, he stays with his two siblings and parents. The last two years in Nagorno Karabakh, he had been living in the capital Stepanakert (also known as Khankendi) with his grandfather, to be able to attend one of the high schools in the city. A couple of days ago, it was his grandfather’s birthday. In late September 2023, the 83-year-old man was forced to leave his home for the third time. Back in 1988, he was living in Sumgait when the pogroms against ethnic Armenians started in the city. He moved to Sghnakh, a village in Nagorno Karabakh, that went under Azerbaijani control during the 44-day war of 2020. Once again, he had to find another home. Stepanakert became that new home, however, only for three years.

The long-lasting blockade of Nagorno Karabakh turned into a war on September 19th. Benjamin was in school. At first, the head of the school told them not to worry, but soon they heard the sounds of shelling. All of them were moved to the basement floor.

“Everyone was screaming, even teachers who had to take care of us without any information about their own children.” Soon, a few buses arrived at the school and took the children home. Benjamin found his grandfather and his uncle’s family in a self-made shelter, where they used to store cans and potatoes. It was wretched and unsafe, so they had to move to a house soon.

Benjamin managed to talk to his mother only a day after. “She told me they were evacuated to the airport of Ivanyan (known as Khojaly in Azerbaijan). I walked alone for almost two hours [to the airport]. I was not scared, I didn’t even have time to think about it.”

A couple of hours after Benjamin reached the airport, it turned out they had to go back home and wait for a decision. Many others, however, who came from the villages that were already taken by the Azerbaijani side, couldn’t go home and had to wait in the airport.

Negotiations between Nagorno Karabakh and Azerbaijan started on September 21st in the city of Yevlakh, the western part of Azerbaijan. A day earlier, the de facto authorities of Nagorno Karabakh agreed to surrender to Azerbaijan to avoid further bloodshed. On September 28, the de facto president of Nagorno Karabakh, Samvel Shahramanyan, announced he had signed a decree to dissolve all state institutions from January 1, 2024.

That day Benjamin found out his history teacher was killed in Sarushen. “This feeling of emptiness made me miss my house right at the top of the village. I knew I couldn’t go back there.” Instead, he was in Stepanakert, and he wished to have left the city earlier, to have the image of the city as he remembered it. Then the gas station explosion happened, and the city became even more chaotic.

The explosion took place at a gas station near Stepanakert on September 25th, in a long queue where people lined up to fill their cars. More than 200 people died, 167 people were evacuated to the hospitals in Armenia, and there are people who are still missing. Up till now, Benjamin and his family don’t have any news from his uncle’s son.

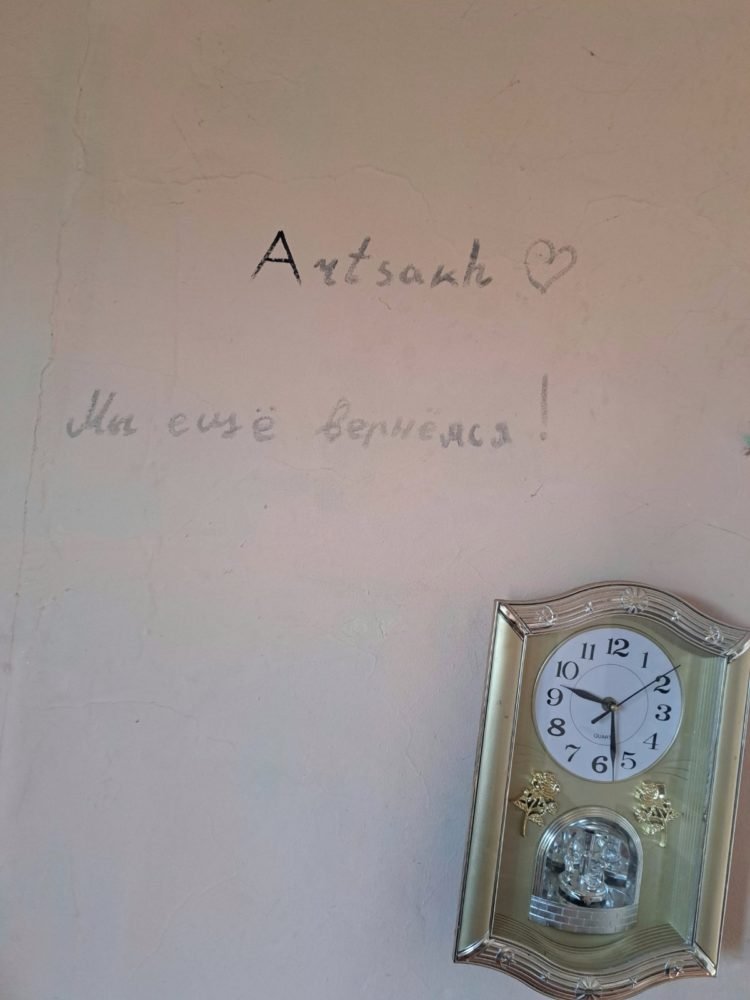

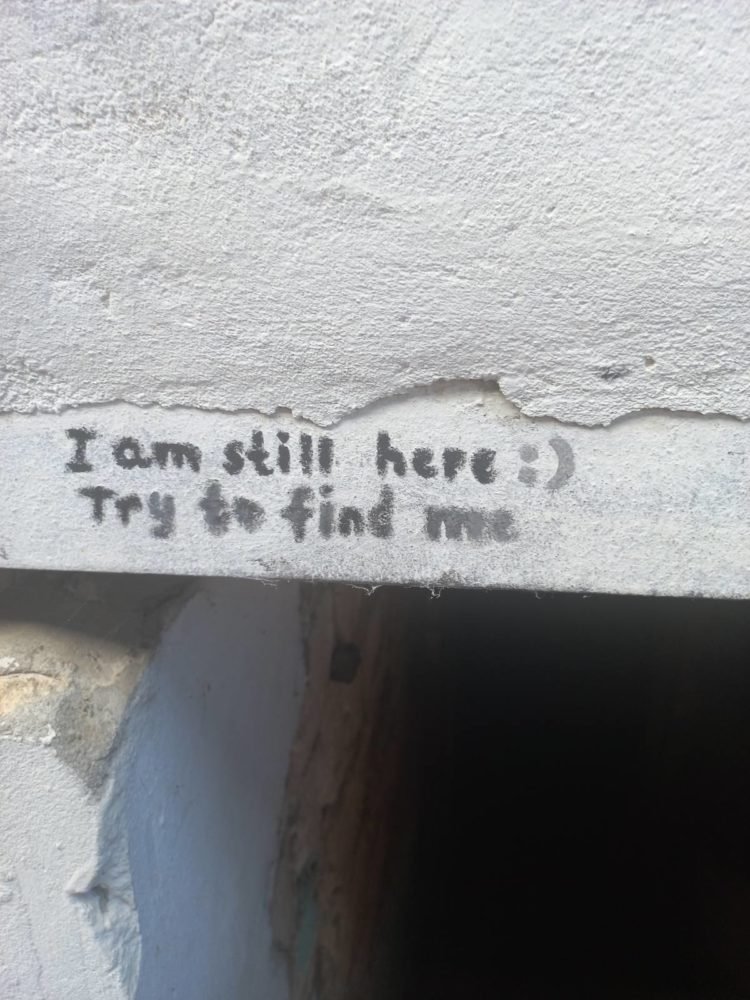

Benjamin’s family left Stepanakert on September 27th. That day Benjamin’s mother cleaned the house. He would ask himself: for whom was she cleaning? Benjamin and his two brothers decided to leave messages on the walls: ‘We will return,’ ‘We haven’t left, look for us.” The streets of Stepanakert were deserted well before their departure. For Benjamin, Stepanakert Square had been a place full of life. But in the last days, he saw starving people taking bread from each other’s hands. It was not the city he used to know.

The bus bound for Armenia stopped at the checkpoint. Benjamin woke up and saw three Azerbaijani officers counting the passengers on the bus. Their journey From Stepanakert to the border with Armenia lasted five hours, but for many who left Nagorno Karabakh in the first days, it took 30-48 hours because of the heavy traffic. Goris, the city that welcomed them, was full of people and full of sweets that were missing in Nagorno Karabakh.

Nushik Mirozyan, an 18-year-old student from the village of Kolkhozashen, had no information about her parents and relatives for more than five days. She is one of the students who passed the Hakari bridge before September, during the blockade, to study in Armenia…

When the authorities in Nagorno Karabakh informed that students could be taken to Armenia with the assistance of Russian peacekeepers, Nushik’s family made the decision that it was the best moment to ‘save their child.’ “At least you can be saved,” – said her Mother. The feeling of being rescued while her beloved ones stayed in danger filled her with guilt. She cried all the way to Armenia.

“Sometimes I dream about the blockade days because I was in my homeland, at least.”

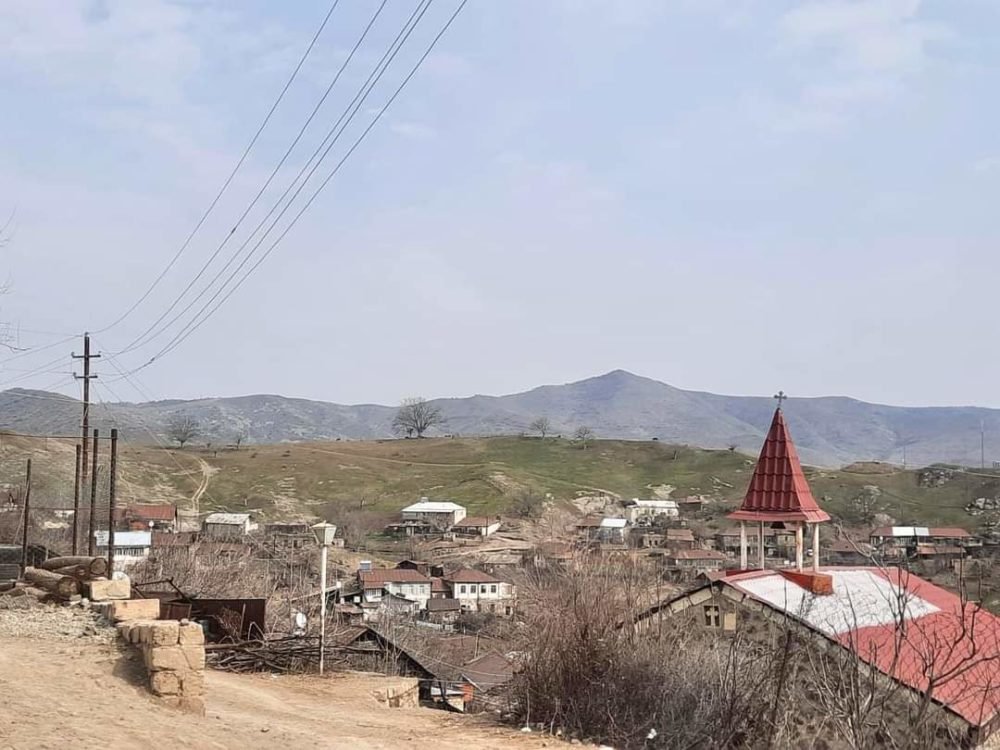

Nushik and her friends, guided by their teacher, established the ‘Jane’ NGO in Kolkhozashen. The village began to experience a vibrant life, a transformation unseen in its history. Nushik delved deeper into her surroundings, uncovering hidden gems to share, not just with tourists but also with the locals.

Now Nushik lives in the ‘Student House,’ a program that provides students from regions of Armenia with non-formal education and accommodation under the same roof. On weekends, the building gets deserted: everyone goes back home, except Nushik. She doesn’t have a place to call home anymore. “I left Kolkhozashen without any doubt I would return. I’ve planned to spend the winter vacations there and celebrate the New Year with my family”.

It was September 19, the day of “Jengyalov Hats” (a traditional Karabakh dish, a bread stuffed with different types of greens), Nushik promised her friends to make the dish. The same day the attack happened. For five days she couldn’t reach out to her family members. When she finally talked to her Mom, Nushik realized her mother didn’t even know about the negotiations and the decisions taken by the de facto authorities of Nagorno Karabakh.

Now her parents’ hope to return home seems unreal to Nushik, but she doesn’t want to make them face the reality. Her parents have rented a flat and live with her brother and sister-in-law.

“When the 44-day war finished, I didn’t hate my peers in Azerbaijan. Now a lot has changed. I don’t know whether I want to fight against the hate or not, [but at the same time] I know that a boy of my age now is in the army of Azerbaijan. I don’t wish for anyone to die; it’s unfair to be young and have a weapon to kill”.

“Young people should fight for their rights, to have a better future. No one should experience war to realize what peace is,” she says.

A view of a mountain covered with lush forest opened up from Nushik’s balcony in Kolkhozashen, “It seemed so close that one could catch it,” she says. “There is no mountain in front of my balcony now; it’s a cold building with no memories”.

Perhaps one day, the traffic lights of Stepanakert will turn from orange to green. However, for the Armenians who have been evacuated from their homeland, the light continues to stay orange, symbolizing the ongoing uncertainty.

Photos by Benjamin, Noushik and their friends.

Cover photo by Ashot Gabrielyan, Noushik’s teacher.