Molokans are representatives of a religious movement that was historically considered to be heretical by the Orthodox Church in Russia for not recognizing the church hierarchy, the images of the cross, and saints, and anything that was not explicitly stated in the bible, including fasting. That is where the name Molokan comes from [moloko (milk) drinkers]. Unlike other Christians, Molokans interpret the Bible metaphorically and symbolically.

In the 1830s, Molokans’ strong opposition to religious establishments and refusal to engage in war provided the basis for their resettlement in the South Caucasus.

Almost two centuries later, Molokan soldiers participated in the 2020 war in Nagorno Karabakh both from Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Any visitor entering the village of Ivanovka will notice a poster of Etibar Shirinov. Shirinov, 27, was one of about thirty miles from Ivanovka who fought in the 2020 Karabakh War. The commemorative poster includes a photo of the armed martyr or shahid — the unofficial honorable title used in Azerbaijan when referring to a deceased soldier — and the war-time slogan, “Shahids are immortal, the Motherland is inseparable,” as well as four lines of his poem:

When leaving I turned around at the doorstep,

And saw my mother whose heart was crying for me.

Was praying for me to God,

I saw my mother whose heart was crying for me.

The village Ivanovka is located in the Ismayilli region, some 200 km northwest of Baku in the foothills of the Greater Caucasus. During the Soviet years, Ivanovka was the largest village populated entirely by ethnic Molokans. However, in recent years the number of Molokans has significantly decreased. Currently, it is home to ~2,500 people; more than half of the population is ethnic Molokans. Molokans were historically considered to be heretical by the Orthodox Church in Russia for rejecting the crosses and icons and were exiled from Russia to distant provinces.

Sitting on the spacious veranda of his private house, surrounded by apple trees and still-immature grapes, Andrei Kharitonov proudly demonstrates his two medals, “For the liberation of Sugovushan and Aghdam,” as well as his military uniform, now tarnished and without pockets. He was the first villager to join the war in 2020.

“On September 28th, my mom asked me on the phone where I was. I answered in the drills, she said I was lying as the war was already announced. We were under heavy fire,” Kharitonov recalls.

Andrei, 29, is in charge of the electric maintenance of grain cleaning machines in the last remaining collective farm in Azerbaijan. He said, “The war is considered an ungodly affair among religious Molokans.” However, the younger generation tends to lean towards the community`s other prescription i.e. obedience to the authorities.

“We live on this land and are obliged to defend it. If we are told to, then we will.”

Andrei says that he reconsidered his internal contradiction to hold a gun after he served in the army when he was 18.

Now he thinks, “If you don’t shoot, they will shoot you.”

Oleg Sapunkov, 26, also participated in the 2020 Nagorno Karabakh War. Now he works as a car mechanic in Sumgayit, a city 27 km from Baku.

When the war broke out in September he was in Ivanovka waiting for a surgery appointment to remove a metal plaque from his leg inserted after a car accident the year before. Instead, he was called to join the war.

“First, I had incomprehensible feelings. Unknown people around. Then fear. It was not clear what was happening around where we were.”

Oleg recalls the mortar shelling of ten fellow soldiers who were out of the trenches and making a type of stairs to carry weapons, supplies, and food uphill during the first days of the war.

“We heard the whistle only and automatically hid in the trenches. But those guys did not have time to.” As a result, one died and the others were wounded.

Oleg met the end of the war near Gubadly, a region in Karabakh not far from the Armenian border. Preparation for this battle was underway as artillery was readied, and soldiers received instructions and painkillers to administer, if necessary, to the wounded to keep advancing. All of a sudden, one of his fellow soldiers received a phone call from home. His relatives made him listen to the live announcement of the signing of the trilateral agreement that ended the war.

“It does not depend on faith, nor does it depend on the nation. This was our duty. No one forced us, we went on our own.”

According to Oleg, there are very few in the younger generation who are against the war, unlike the elder ones.

However, Oleg and Andrei say that those who are against the war prefer to not express their opinions publicly. The only place where they can discuss it is the community`s prayer house, which is currently under reconstruction.

“This is the individual choice of each Molokan. If someone wants to refuse, he will. Whereas, if he has even a drop of patriotism, he will go and do it,” Andrei concludes.

Isolated in the mountains, a village Lermontova, is located 11 km from Vanadzor in the north of Armenia and is populated by mostly Molokans but also Armenians and Yezidis.

The war through the eyes of Lyudmila.

Mixed marriages are not common in the village of Lermontova. The story of Lyudmila Shubina and Bekchyan Armen is one of the few exceptions. The couple has two sons, their youngest, Yura Shubin, participated in the second Nagorno Karabakh War when he was 22 years old.

“He served in Hadrut, then his regiment was taken to Martuni. Half of his regiment has died,” Lyudmila began her son’s story․ During the war, Yuri himself didn’t expect to survive.

“Bullets rained down on him, but didn’t hit him,” Lyudmila says. �“When the enemy attacked, there were many difficult moments, they [Azerbaijanis] even wanted to take prisoners. It was God’s will; my son survived. Now he is already married, he has a family, and he helps us”․

Yuri has now moved to Artashat, works, and lives there.

The War and Katya.

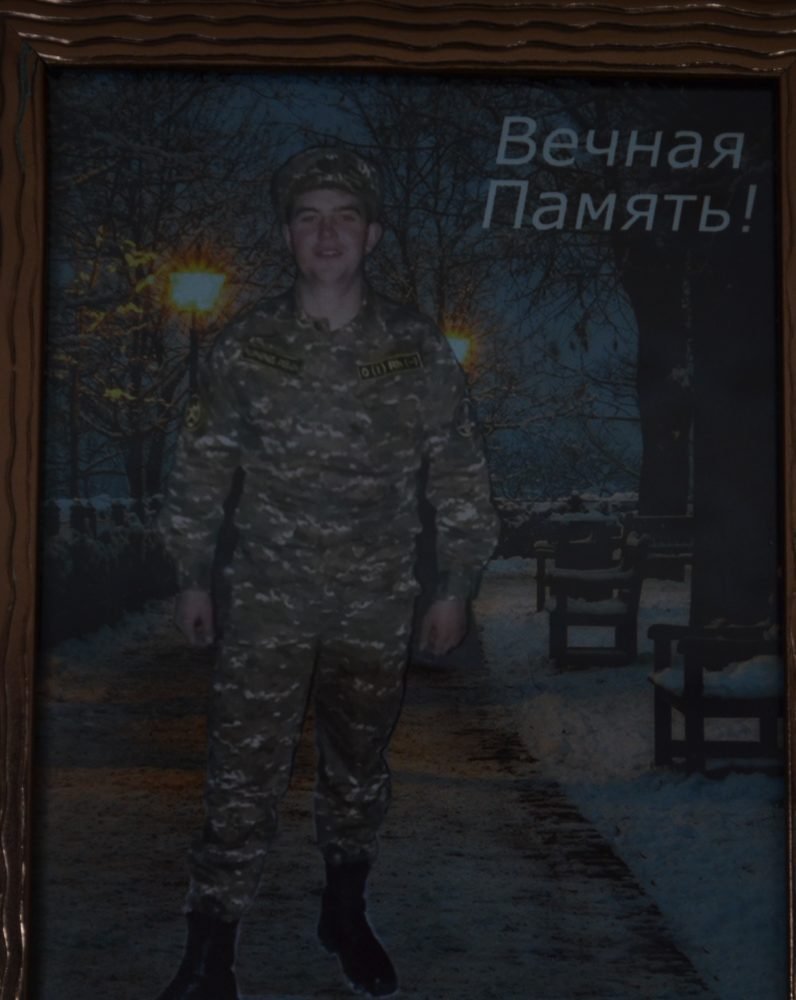

In Lermontova, when one asks about the war, people remember Alexander and his grandmother Katya․ Alexander died during the second Nagorno Karabakh War․

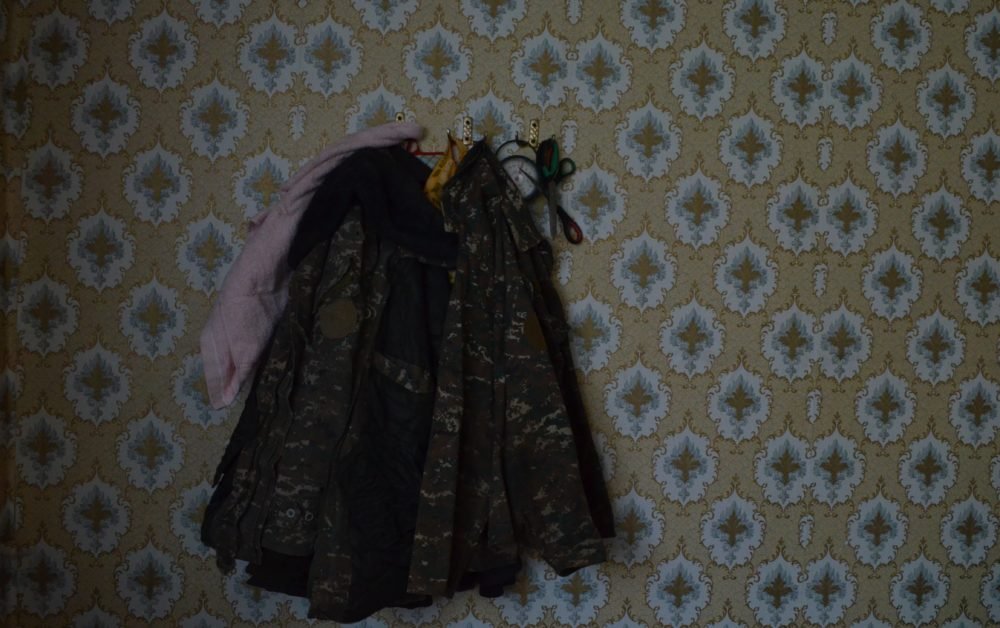

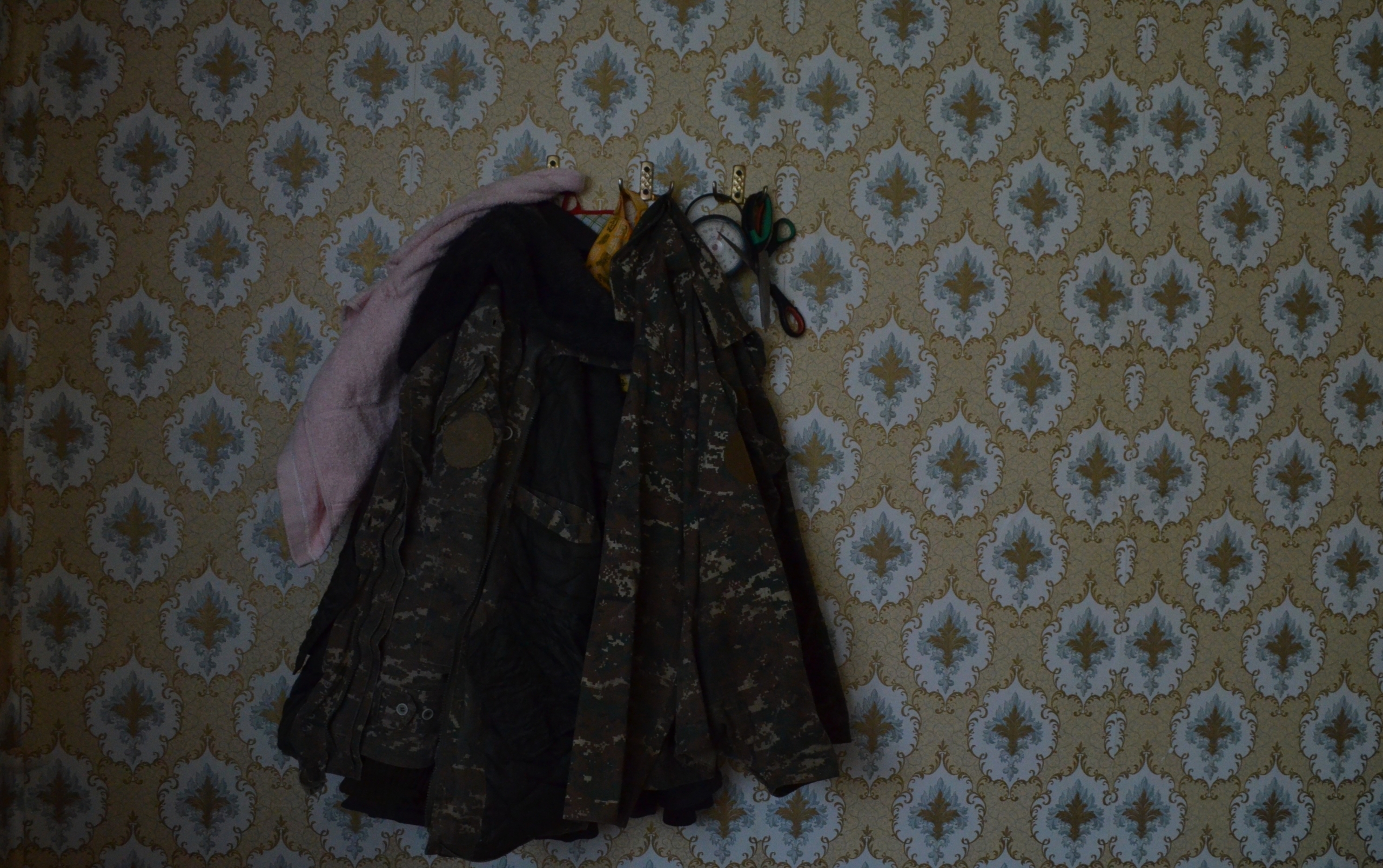

Katya lives alone now in an area called Antarashen [Agvesner by locals]. It was once a separate village but after the enlargement of the communities, it became part of Lermontova. In Katya��’s house, one of the first things one would notice is Alexander’s military coat.

“The enlistment oath is not mandatory for Molokans, but my son (she calls him a son) learned everything in Armenian, because he was the only Molokan in the military unit, and he took the enlistment oath in Armenian,” Katya said proudly, adding, “He wanted to become a soldier since he was a child.”

She remembers how Alexander liked the place in which he carried out his mandatory service, he even wanted them to move there. At the enlistment oath, he said,

“Mom, everything is very good here, everyone is good. There is a very nice village a little above here. After I finish my military service, I would like us to move to that village.”

Alexander was born in 2001. He enlisted in the army in the summer of 2019 and served in the Martakert region of Nagorno-Karabakh. He died in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in October, 2020.

Katya remembers the last conversation between her and her grandson,

“It was Sunday. He called in the morning and asked how things were going.” By that time four or five days had passed since Katya had any communication with him.

“Mom, don’t call me until I do,” he told her. And on that very day, he said, “Mom, we don’t have a commander, it’s as if we are thrown here.”

“These are his words, after which the order to go up was heard and he said: “Okay mom, we’ll talk later.” And he never called again.

The next morning, I noticed that people in the village had gathered and seemed to be discussing something. It turned out that the whole village knew about my son’s death, except me. At that moment, two children approached, I asked them what they wanted, and they said, ‘nothing, we just came,’ and ran away. Then I found out that they took them to the morgue at night, but I didn’t know anything.”

Katya, even in poor health, keeps a red horse. It was her grandson’s request.

“I have a red horse here, my son used to say, ‘Mom, sell all the horses, but keep the red horse.’ That’s what I did. I kept it to this day.”

Talking about Alexander’s dreams, Katya mentioned that he wanted to move to Nagorno Karabakh and live there after finishing military service.

As for Katya, she now dreams of peace.

“I have lived here all my life and I would like everything to be peaceful, as it was before. Everyone wants to live in peace, serve in peace.”