The unresolved Georgian-Abkhaz conflict of 1992-1993 had a severe impact on people living on each side. For over a quarter century children and youth have continued to experience multiple challenges due to political uncertainty and isolation. Due to a lack of recognition, the inhabitants of Abkhazia are often subjected to various types of discrimination and human rights violations in humanitarian, cultural, and educational spheres.

In 2011, a KVN team (Comedy Club of the Funny and Inventive), “Narts from Abkhazia,” could not take part in the KVN festival held in Latvia due to the Latvian Embassy in Russia refusing to give them visas. They were accused of possessing fake Russian passports. The accusation was false as, like many other residents of Abkhazia, all team members had received Russian citizenship on official grounds.

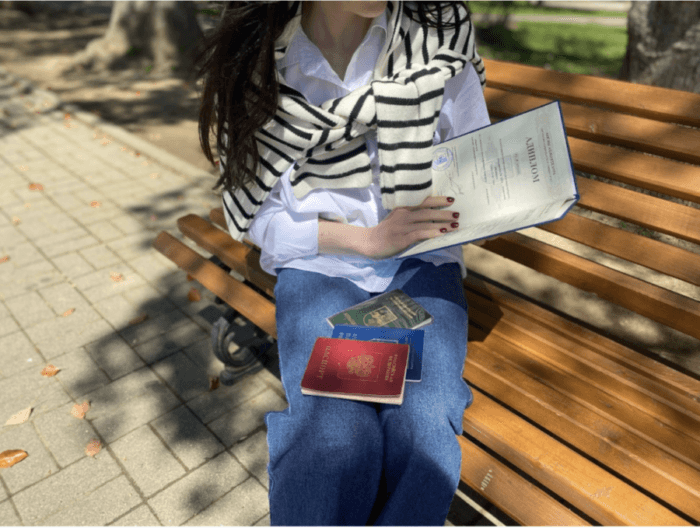

Abkhaz passports are recognized only within Abkhazia and do not permit foreign travel, with the exception of Russia. Receiving Russian passports gives the residents of Abkhazia the right to travel around the world, a right which they had been previously deprived of for a long time. There are numerous cases of children’s dance ensembles not being allowed to perform in art and cultural festivals. In many cases children were prevented from going onstage on the day their performance was scheduled as the Georgian Foreign Ministry would often intervene, announcing a note of protest.

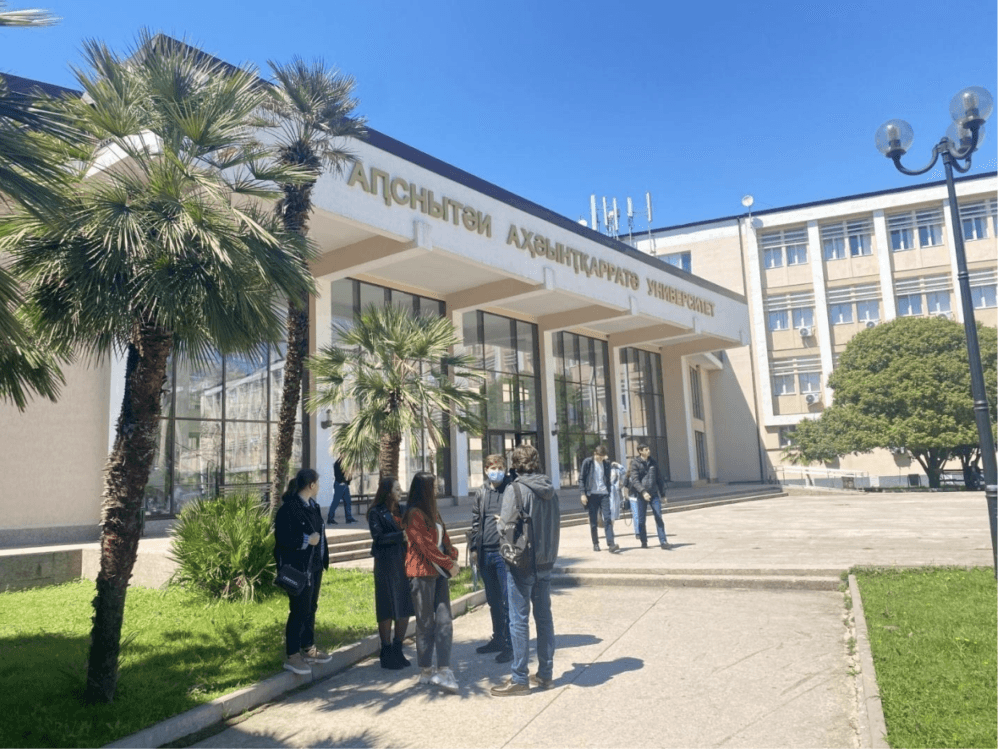

Yet the most significant problems occur in the field of education, particularly with regard to the accessibility of European and other foreign educational opportunities. The world denies Abkhazians the ability to travel and continue their higher education anywhere except Russia, though many desire to study in European countries or in the United States of America.

Students who have received higher education in Abkhazia or Russia apply for various international scholarships. There are two types of scholarships available for young people from Abkhazia: the Chevening Scholarship (UK) and the Rondine Scholarship (Italy). Within the Chevening scholarship program, 1-4 spots are annually allocated for Abkhazians, allowing them to study at British universities. For those wishing to receive an education in Italy within the framework of the Rondine Citadel of the World Association program, a Russian diploma is a prerequisite and only one spot is allocated for Abkhazians each year and a half. Today, these are the only official opportunities provided for Abkhazians to continue higher education in European universities.

Due to the fact that the majority of the international community does not recognize the independence of Abkhazia, neither the Abkhaz government nor state university is able to create international study partnerships with foreign educational institutions. However, Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia and its university has allowed the formation of the institutional partnerships necessary to make international study easily accessible. Therefore, the citizens of Abkhazia who want to continue their studies in Europe or elsewhere do not rely on state programs and admission quotas because they only include Russian universities. Instead, they try to find educational programs independently and enter universities in Europe and America. But this is not a simple process, as Abkhazians attempting to travel for education are often denied visas. Abkhazians’ journey to access to European or other foreign education often ends up revealing itself as a long and thorny path, if not an altogether impossible expedition.

Several years ago, Aslan participated in a student exchange project which involved a year of study at a university in the United States of America. Aslan was one of the Abkhazians who passed a competition in Kyiv to be enrolled in one of the American universities in Iowa. According to Aslan, three more Abkhaz were selected in the same program at that time and all were awaiting the process of obtaining a visa.

“I would like to note that when we first talked about the program, before participating, we clarified which passports we should use for traveling, as citizens of which country. We were then told that we should travel as citizens of Russia, ” Aslan said, making it clear that there had been agreement on those terms.

Yet just before leaving for America, the young Abkhazians who entered the university were told that “the circumstances had been slightly changed” and there was a new condition that they could only get American visas with Georgian passports.

“We were told that the Georgian side influenced the organizers and made it so that no one from Abkhazia would be able to go.” Aslan recalls. “They made it clear to us: Abkhazia is a part of Georgia, so Abkhaz students must travel through Tbilisi using Georgian passports.”

According to Aslan, they were even offered the option of solving the issue; the organizers told them that travel to Tbilisi was not necessary and the issue could be resolved through Kyiv, but for the students this option was unacceptable. They refused both passports and studied at an American university.

Later, an Abkhazian official, Sergey Shamba, decided to solve this problem. He announced he would not attend the next round of Geneva discussions if the university students were denied the opportunity to obtain visas and study. Shamba was even promised that the problem would be resolved with a positive outcome. Aslan and his friends were invited to Kyiv — the embassy promised to issue them visas there — but once in Kyiv, they discovered that their names were no longer on the lists of applicants.

Aslan is sure that this incident is a direct consequence of the Georgian leadership’s unfair policies, which restricts his rights and the rights of other people from Abkhazia to free movement and education. He is sure that there are other examples across the world in which citizens of unrecognized and partially recognized states still have the opportunity to receive education in Europe or America without any delay. Citizens of Northern Cyprus or Kosovo, for example, enjoy such opportunities.

Alisa, a graduate of Abkhazian University, has a story of her own. With an Abkhazian diploma, it was quite problematic for her to continue her education at a European university. Once, she found she could not even attend a youth camp in the UK. Although she passed the competition on a general basis, she was denied a visa. The denial notice stated: “falsified passport”. But Alisa did not give up. For about three years she searched for educational programs that would not discriminate against her passport. As a result, she managed to enter university in one of the IREX programs, at Maryville College in the American state of Tennessee.

“There were a lot of obstacles then, too,” recalls Alisa, “they wanted me to apply for the Georgian quota so that I could go through Georgia, they said that it would have been very easy to get a passport, but of course, it was not acceptable for me.”

Clearly, the fact that Alisa was eventually admitted to this university was not a usual case, but the result of her own perseverance.

“I can easily say this now,” recalls Alisa, “but these were very, very long negotiations, I wrote them a lot of letters, sent letters all day long, and in the end, they invited me to Kyiv. I don’t know if it was technical problems or intentional, but I passed the test three times, because, according to them, my voice was not recorded, then something else, I cannot sin by saying that they deliberately created obstacles, but in general, it was very difficult for me to enter.”

Many Abkhaz residents are aware of Georgian educational options, such as the Step to a Better Future program, which allows Abkhaz students to study at Georgian universities without exams and free of charge. But each of the respondents stated that although it sounds tempting, any option through Georgia does not suit them as, according to them, it contradicts their ethical principles and norms. One of the respondents, who also tried to enroll in an international study program but was unsuccessful, said that she was offered the option of Georgian education, but she refused.

“No matter how much I want to get a European education, I can’t go through Georgia, it means betraying myself and my loved ones.”

Virtually all students from Abkhazia who attempt to continue higher education in Europe face an array of similar obstacles — even those who manage to enter foreign universities and graduate. These arise in the form of so-called “falsified passports” or “incorrect diplomas”, and they are often simply refused visas if they will not use Georgian documents. These complications engender a situation in which fewer and fewer people try to apply for any visas other than Russian visas, as the Russian process is notably smoother. Primarily because there are ample quotas for Abkhaz students and Abkhaz documents and diplomas of education are recognized there.

Overall, this all contributes to the formation of a pro-Russian community of young professionals who have studied in Russia. It is these people that are the future establishment of Abkhazia, and in their minds their experiences with discrimination and the violation of their rights to education and movement are firmly embedded. It goes without saying that every person should be able to exercise these rights as a human birthright, not burdened by the structural injustices of double standards and so-called political realities.

Archived comments

When you do not respect international society, international society also does not respect you, especially if you are a failed state even in the eyes of your supporters

So, Russians forced 300 000 Georgians to move from their homes, because of their ethnicity and now you complain about education?

First people have to return to their homes, then you can discuss freedom of choice of European education.