Against the Binary, Toward Decoloniality

Introduction

The South Caucasus stands at a crossroads of shifting orders and borders, witnessing the crumbling of democracy around the world under the weight of local autocracies and global exploitation. In Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, the promises of sovereignty and freedom have been weaponized—reduced to pipelines, checkpoints, and broken electoral systems. Meanwhile, people are pushed into silence, exile, prison, or living on the bare minimum.

This article is a call to reimagine autonomy beyond the worn-out scripts of the West and Russia. It is a call for [radical] decoloniality—for a future that begins from the ground up, from local struggles, solidarities, and imaginations that have always existed beneath the surface of empires and states.

What if the region's future did not lie in choosing between competing imperial patrons? What if it lay in rejecting the binary altogether—and building something new, something radically our own?

Beyond the Binary: Exposing False Narratives

The political imagination in the South Caucasus has long been structured by a binary between the pro-Western liberal promise of democracy versus the pro-Russian rhetoric of “promised stability”. Both sides, with their own colonial flavors, leave little space for genuine autonomy in the region, forcing people either to believe they must be “saved” by Western democracy or to stay a Russian colony forever.

However, this simplistic framework fails to capture the region’s complexities, historical legacies, and aspirations for genuine autonomy. It not only limits the [im]possible pathways for local liberation but also traps communities in a continuous state of deprivation of fundamental rights. Meanwhile, autocrats — aided by international powers — thrive on the suffering of their people and the theft of the region’s natural resources.

Historically situated at the crossroads of empires, the South Caucasus continues to be shaped by overlapping geopolitical pressures. Turkey, Iran, and Russia are major adjacent players in the region, controlling dominant political and economic agendas. The USA, EU, China, and other global powers, while so far and so close, with their presence, ultimately benefit their own capital interests far more than the local communities.

To view Europe as a liberatory force and Russia as the sole colonizer erases critical discourses in the region. Russia is undeniably a colonial power: from Tsarist times to Soviet rule and beyond, it has imposed linguistic, cultural, and political control over the region. However, Europe is also deeply entangled in imperialist dynamics, currently exerting hard and soft power through mechanisms like the International Monetary Fund, EU Association Agreements, and NATO. The EU conditions the “development” of the region on its liberal democratic values and neoliberal reforms — models that have failed within the EU itself.

Neoliberalism, which promotes so-called free markets, minimal states, and borderless capitalism, in reality, is a network of powerful states, institutions, and elites enforcing a system that privileges their capital over so-called democracy. While some core states set global rules and benefit the most from free markets, the local elites come to the aid of global elites to exploit a country’s resources, including the people’s labour. The states' political elites benefit personally and politically from aligning with global capital; they are active agents in global capitalism. They serve global capital in order to secure and consolidate their internal power. They privatize industries for personal gain by suppressing labour and social movements in their countries.

As Quinn Slobodian, professor of International History at Boston University, puts it in his book “Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism”, the real focus of neoliberal proposals is not on the market per se but on redesigning states, laws, and other institutions to protect the market which is in the hands of the powerful.

In the South Caucasus, Europe is often associated with good living conditions, human rights, democracy, freedoms, and “civilization,” says Arpi Balyan, co-founder of FemLibrary in Yerevan. Yet she cautions that this is a selective and incomplete picture. Balyan notes that media portrayals and the work of EU actors have played significant roles in constructing this favorable but misleading image. Much of the funding spent by international donors in the region goes toward producing “attractive-looking” reports for funding organizations rather than fostering real systemic change in the local country.

“There is no luxury in criticizing the EU in Georgia,” says Mariam Nikuradze, OC Media co-founder. As Georgia descends into authoritarianism, criticism of the EU could inadvertently benefit the ruling Georgian Dream party. In this precarious political moment, she suggests, a deeper critique must be postponed for calmer times.

She recalls that in Georgia, the discourse of freedom and democracy has long been framed as a binary: Russia vs Europe. She highlights the lack of deep understanding about what these concepts truly mean and the absence of alternative narratives. This binary framing has also influenced the media coverage and focus of the recent protests, describing them as “pro-European” — as the only perceived pathway to democracy.

The slogan “I am Georgian, and therefore I am European," wrapped in EU flags at the protests in Tbilisi, minimizes the multilayered nature of the South Caucasus by limiting critique of the EU and narrows the meaning of what it is to be “European.”

Sevinj Samadzade, a feminist researcher and co-founder of the Feminist Peace Collective, reminds us that being European today also means being complicit in ongoing genocide in Gaza. Europe, she adds, still embodies colonizing forces and perpetuates neo-colonialism in the South Caucasus, by making it an extractive zone for Western capital, including the UK, the US, and France.

Samadzade highlights the geopolitical trap that emerges when people in Georgia are forced to choose between competing imperial formations—Russia on one side and the Euro-Atlantic bloc on the other. While acknowledging the deeply colonial legacies of Russian domination, she argues that the current desire for EU integration also deserves scrutiny for the neoliberal dependencies it cultivates through financial, political, and institutional ties. In her view, what people in Georgia are ultimately demanding is not merely alignment with the West, but autonomy, dignity, and social welfare. Becoming part of the EU may appear as a logical path toward these goals, but Samadzade stresses the need to leave space for criticism of how Western structures reproduce extractivism and inequality in the region. For her, true liberation lies not in choosing one geopolitical axis over another, but in creating political imaginaries that center people’s material needs and histories and imaginaries that move beyond the binary of integration versus isolation and toward collective autonomy and justice.

The Mirage of Democracy: Armenia’s Betrayed Hopes

Simply achieving “democracy,” as promised by the so-called international community, will not automatically bring about the dignified lives people deserve. At best, it risks producing a well-groomed autocracy. This set of demands and frameworks cannot deliver true justice because it fails to accommodate class solidarity and prevents the region from imagining a future beyond pipelines and military alliances.

The idea of democracy was initially alluring for Arpi Balyan after the 2018 so-called Velvet Revolution, when she witnessed the role of ordinary people in political participation. Yet only a few years later, she realized that the dream of becoming a genuinely democratic country had faded once government promises, as always, vanished. It wasn’t a revolution for Balyan: merely a change of leadership within the existing structures of liberal democracy. This kind of democracy, for her, continues to benefit local elites while leaving ordinary people behind.

While the Armenian police are considered relatively “democratic” — not displaying the same brutality seen in neighboring countries, this is simply because the state has not yet ordered them to act violently. It would be naive to believe that, when commanded, the police would not enforce repression; after all, the police are ultimately tools of the ruling class, deployed to protect the state elite's interests when necessary.

In Armenia, the judiciary remains deeply corrupt, wages remain disconnected from the cost of living, and gentrification in Yerevan is intensifying, deepening neglect in the country’s provincial regions. Meanwhile, the capital’s air quality now exceeds World Health Organization guidelines by nine times, making it the worst in the South Caucasus.

Following the co-optation of the people’s movement, rebranded as a "revolution," Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan ordered the opening of the thick metal gates surrounding the Armenian Parliament. These gates had been one of the central protest sites during the uprisings in Armenia for many years. Surrounded by a park, Parliament became one of the few remaining green public spaces in central Yerevan — a rare oasis of accessibility. However, after around one year, when new waves of protest arose against Pashinyan himself, the gates were closed again — this time permanently. Did that exact moment mark the death of the promised democracy in Armenia?

Multipolar Exploitation: No Saviors on the Horizon

Following the Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine wars, the region’s political map shifted dramatically. Today, there is no single dominant power — or even a stable duo of powers — that can fully control the South Caucasus, says Emil Avdaliani, professor of international relations at the European University in Tbilisi. He says it reflects geopolitical changes in the world, where the emerging multipolar order introduces a new set of rules. He believes the South Caucasus has moved beyond the simple binary of Russia vs. West, evolving into a more multi-aligned regional configuration. Although these countries can be seen as insignificant with small economies, their geopolitical location still makes the region important, playing a significant role in the global political shifts.

As a critical transit corridor, the region enables the movement of energy resources from the Caspian Sea to Western markets without passing through Russian or Iranian territory. It hosts vital pipelines and transport links, including the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline, the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum gas pipeline, and the Middle Corridor connecting China to Europe.

The BTC, the second-longest oil pipeline in the post-Soviet space following the Russian one, spans 1,768 kilometers, linking Azerbaijan’s Caspian coast to Turkey’s Mediterranean port at Ceyhan via Georgia. Supported by the US and the EU, the BTC reduces Russian influence over Caspian energy exports, undermining a traditional source of Moscow's global and regional leverage. Yet the search for alternatives to Russian gas has pushed the EU to forge new alliances with other authoritarian regimes, like Azerbaijan. Securing its energy needs has meant turning a blind eye to the Aliyev regime’s brutal crackdowns on civil society. The Southern Gas Corridor, a 3,500-kilometer network from Azerbaijan to Italy, now channels Azerbaijani natural resources to Europe, accounting for 92% of Azerbaijan’s exports. This not only entrenches Aliyev’s dictatorship but also profoundly affects the political and economic fabric of the entire South Caucasus.

The pipelines are not merely infrastructure — they are also geopolitical fault lines benefiting the war economy and harming the locals once again. The pipelines run in a territory of never-ending or frozen conflicts, like Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia, which remain flashpoints for instability.

Sevinj Samadzade emphasizes that the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and broader regional resistance cannot be understood without confronting the layered entanglements of imperialism that shape the South Caucasus. Rather than viewing change as contingent solely on geopolitical shifts in powers like Turkey or Russia, she stresses the need to examine how imperial interests, both external and internal, have historically enabled and sustained local authoritarian regimes. In the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, she argues that the conflict has been instrumentalized by local elites, including the Azerbaijani government, to consolidate power through narratives of nationalism, militarism, and patriarchal control. These dynamics are reinforced by global and regional powers’ strategic and economic interests in the region. For Samadzade, resisting this framework means not just opposing authoritarian rule, but also interrogating how geopolitical calculations and imperial legacies continue to define the limits of peace and justice in the region.

The South Caucasian local autocrats exploit the global geo-political situation to consolidate their power, ironically invoking “sovereignty” or “stability” to justify their repressions or “reforms.” They weaponize external threats to legitimize surveillance, wars, censorship, and the targeting of activists, queer communities, journalists, and leftists. This environment pushes people to withdraw from formal politics, retreating into apathy, mere survival, or quiet forms of resistance. However, as long as the concept of the state exists, its mechanisms will continue to be reproduced. By their very nature, states drive us into wars and divisions—because the global economy profits from conflict, and local elites gain power and wealth. To secure and prolong their authority, states rely on nationalism. It strengthens state propaganda and turns national identity into a dominant part of people's self-understanding, eclipsing other, more personal or communal identities.

The Struggle for Real Autonomy: Building Beyond States and Empires

There is a genuine desire for autonomy and independence in the Caucasus, but the key question remains: How autonomous can nation-states in this post-Soviet space truly be?

Arpi Balyan suggests reexamining freedom from a decolonial perspective to seek autonomy by reducing dependence on global powers. Sevinj Samadzade suggests autonomy in the region by building alternative economies. Without this, she believes, the South Caucasus will remain trapped within the chain of coloniality. She stresses that the region must find ways to collaborate and use its resources wisely, fostering economic interdependence between Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia.

Yet, the region’s socio-political realities pose challenging questions: how can countries whose relationships are built on wars, competition, hatred — or at best, indifference — find paths toward connection?

The long-lasting Nagorno-Karabakh war left its stamp on local interconnections, creating total division between Armenian and Azerbaijani societies, strained by grievances from the wars, while leaving Georgia in between, dependent on the Azerbaijani economy and being on “good terms” with Armenia. Historically, Georgia has served as a bridge between Armenians and Azerbaijanis. However, today, even that role has become precarious, particularly amid the rising authoritarianism within Georgia itself. Its future as a safe meeting ground is becoming increasingly uncertain.

Mariam Nikuradze notes that Georgia’s democratic backsliding has profound consequences for the entire South Caucasus. " Many Azerbaijanis who are politically involved are leaving Georgia because they are rightfully afraid," says Nikuradze.

The arrest of Afghan Sadigov signals that even those who have fled authoritarian Azerbaijan no longer find safety in Georgia. Nikuradze points out that Georgia's once-small space for Armenian-Azerbaijani dialogue is shrinking, if not disappearing altogether.

Nikuradze notes that Georgian media coverage of Armenia and Azerbaijan remains shallow, typically limited to major political events without real public engagement. She laments the lack of enthusiasm in Georgia for fostering regional interconnectedness. At the government level, there is some focus on trade, economy, and transport corridors, but genuine connections between the people of the South Caucasus remain rare.

“Unfortunately, there are not many spaces where people in the Caucasus can cooperate and do things together,” says Nikuradze. “There are some initiatives, but their scale is very small, and their impact is limited.”

Radical Decolonial Futures: Reclaiming Our Own Path

As the region descends deeper into autocracy, the predominant strategies adopted by the opposition still lean on the hope for salvation from international actors, at a time when the West itself is sliding toward authoritarianism. The grim truth is: no one is coming to save us. We must do it ourselves if we are to reclaim autonomy and a future worth living.

The rapid global shifts and the rise of far-right governance dismantle the illusion that the solution lies outside. Instead, they expose a brutal reality: the South Caucasus is geopolitically significant precisely because it can be exploited — and it will, unless we resist. It demands building equitable, interconnected economies that serve the people, not the elites. If there is a brighter future for the South Caucasus, it will not come from choosing the "right" side of a geopolitical binary. It will come from breaking the binary entirely — and building something rooted, collective, and radically free. And for that, we need, let’s call it, radical decoloniality.

Radical decoloniality in the South Caucasus would mean a profound, systemic rethinking and dismantling of colonial legacies—not only from external imperial powers like Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Persia, and the West, but also internalized forms of domination, hierarchy, and epistemic control that persist today. That will mean taking an anti-extractivism position by opposing the exploitation of land for mining and of pipelines for their global capital. Radical decoloniality in the South Caucasus would mean creating an anti-nationalist solidarity by challenging state-imposed ethnic divisions and binaries that have led to hatred between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, Georgians and Abkhazians, and beyond.

But how do we begin to heal from the wounds left by years of mourning? How do we forgive those who, like us, are also victims of state propaganda?

We must start by eliminating dehumanization. We must seek out what connects us—our shared histories, our regional solidarities—and understand what steps are necessary to dismantle the toxic environment created by the states. We need to break through the artificial psychological barriers between us. We must talk to each other, listen to one another, and try to understand—even when the only exposure we've had to each other's languages or cultures has come through the media, shaped by narratives of war and fear. Instead of competition, we must embrace our similarities and relearn how to share. We should not allow geopolitical borders and imposed narratives to define us. We must decide for ourselves how we are connected.

While in the search for independence, decoloniality is reduced to narrow nationalist projects in the small nations in the Caucasus. Through radical decoloniality, we can reject nationalist mythmaking and undo dominant historical narratives shaped by Soviet, imperial Russian, pre-Soviet local intelligentsia, or post-independence elites that erase alternative resistances. Radical decoloniality in the South Caucasus, then, isn’t just about changing political regimes—it’s about transforming how people relate to each other, to land, to memory, and to the future. It’s an invitation to refuse and reinvent at every level. Radical decolonization will require rejecting all imperial patrons; It is about breaking the cycle entirely and refusing the binary altogether. It means recognizing that sovereignty cannot be granted by empires and states. It must be built from the ground up—by the people, for the people. It is anti-colonial in the deepest sense—interrogating how power functions, how knowledge is produced, and how lives are valued or discarded.

A truly decolonial path for the South Caucasus requires centering regional solidarity over global alignment. Solidarity between movements across borders, instead of “project-funded” activism. It should prioritize and elevate local knowledge and practices that have long resisted empires: local and mutual traditions, linguistic and culinary similarities, and multilingual historical coexistence. And most importantly, it should build autonomous institutions that serve people, not patrons—no wars, free press, grassroots unions, feminist and queer networks, independent education, healthcare.

Radical decoloniality refuses the scripts handed to us and starts from local histories, epistemologies, and struggles rather than importing ready-made solutions. Radical decoloniality requires a more nuanced way forward, recognizing the region’s agency. It begins with radical listening, centering marginalized voices, and unlearning the ways we’ve been taught to speak, think, and feel. It also requires risk. It means rejecting recognition from both the state and the international community. It means being accountable only to the people you struggle with. Finally, it requires imagination. Radical decoloniality is not about purism or perfection. It’s about experimentation, messiness, and contradiction. It’s about building new forms of life in the ruins of empires and states.

Borders Are Not Ours

The South Caucasus will not be saved by elections staged under occupation. It will not be liberated by pipelines owned by foreign corporations. It will not find freedom by aligning itself with fading global powers that see the region only as a battlefield or a corridor.

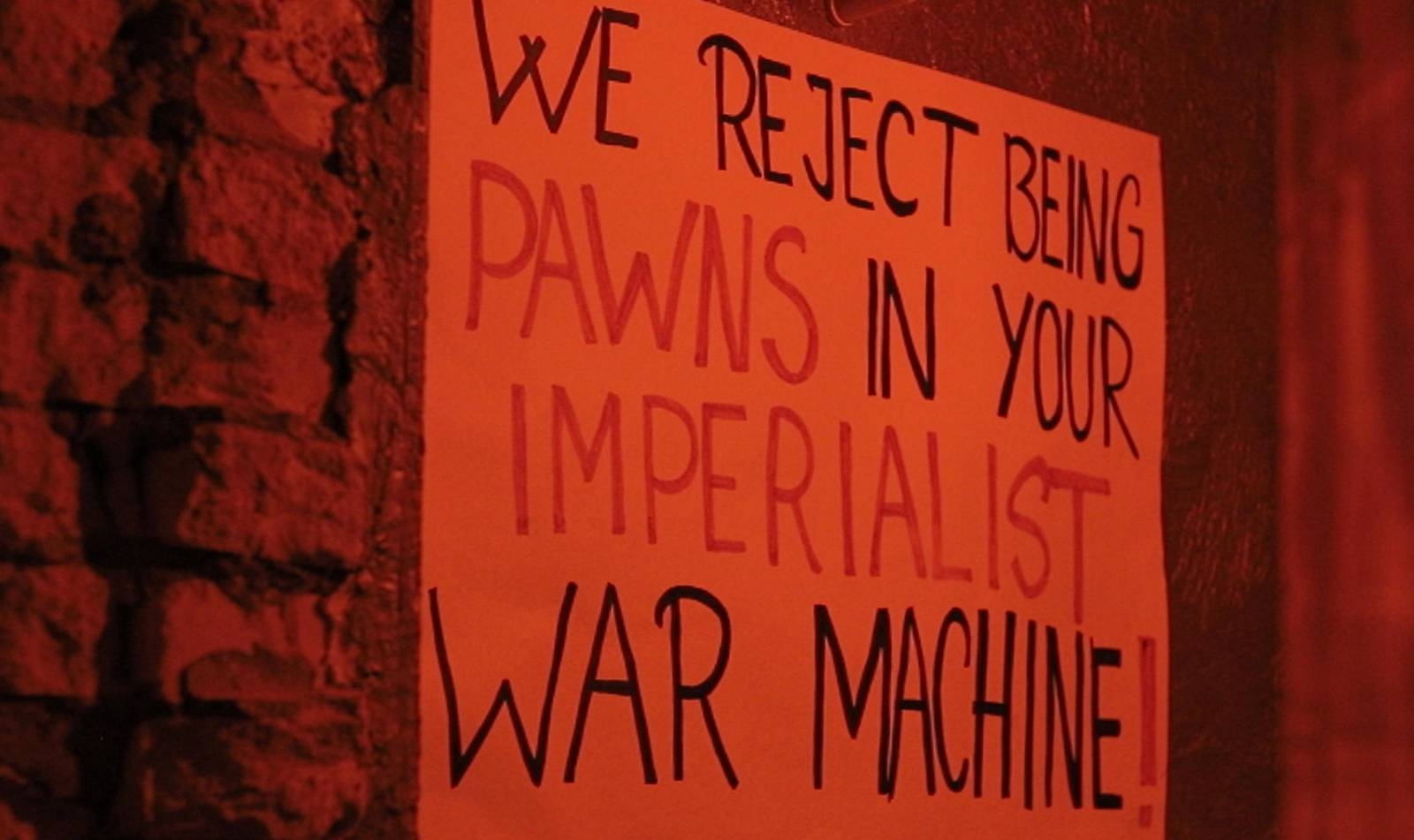

If there is a future here, it must be built through regional solidarity, radical imagination, and the reclamation of our own histories, lands, and ways of life. Decoloniality is not a distant dream—it is already happening, quietly, in every act of resistance, in every refusal to choose between oppressors, in every attempt to create something rooted and free. The choice before us is not between Russia and the West. The choice is whether we will continue to be pawns in someone else’s game or whether we will finally write our own future.

No empire or state will grant us freedom; we must take it ourselves.