This story has been recounted by Zarif Bakirova, a community mobilizer in Mingachevir.

It all began with a simple idea in 2021: to draw graffiti depicting a girl in a school uniform with a skirt below the knees and the saying “Bir qızın təhsildir zinnəti” [Education is a girl’s treasure] by Azerbaijani writer Huseyn Javid on the wall of one of the buildings in an IDP settlement in Mingachevir.

I moved to Mingachevir in 2019 to start my new job. Before that, I lived in Baku, so moving out of the capital was both interesting and challenging at the same time.

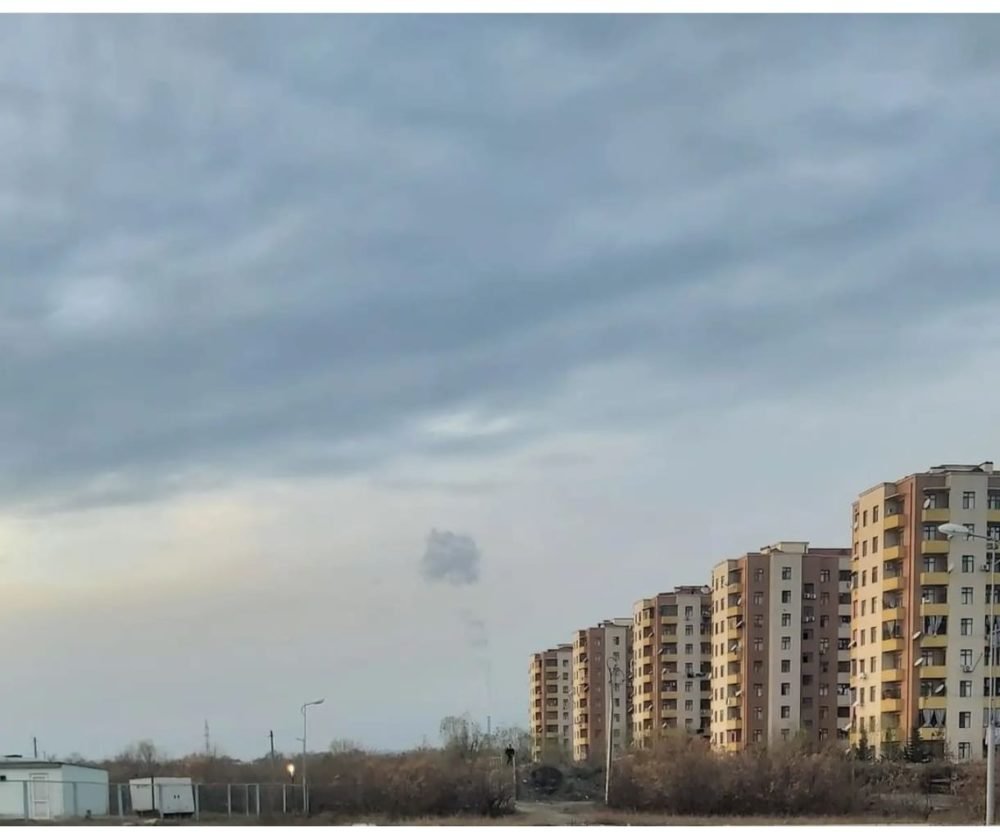

Mingachevir is the fourth biggest city in Azerbaijan, located 300 km away from Baku, with a population of 136,000 people, 30,000 of whom are internally displaced people, mostly from the Agdam and Kalbajar regions. After the first Karabakh war, IDPs settled in different parts of the city, but in 2014 they were all moved to a newly constructed settlement.

Each settlement comprises 10 buildings, each with 9 floors, and three apartments on every floor. The buildings are renovated, have elevators, and there is a central heating system. Although the conditions here are better than in the places they lived before (dormitories, old hotels, etc.), the IDPs feel more alienated and less integrated with the local population. Living on the outskirts of the city and needing to take public transportation to get to the center adds to their sense of isolation. While paying 0,80 AZN (0,50$) may not seem like a significant amount, it accumulates for members of this community.

Most of the IDPs attend school according to their registration place and do not interact much with the local population, which has a detrimental effect on their development. Many children leave school after the 9th grade, either to attend college, work, or, in the case of girls, to do housework or even get married.

In 2021, as a community mobilizer working with internally displaced people, I established a community center for various activities for local youth. Graffiti on the wall of one of the buildings was one of those activities. However, over time, the writing was erased, and the girl’s image was overlaid with black paint.

The members of the community decided to restore the graffiti. We enlarged the picture, added a boy, and restored the writing. We turned it into a big event, complete with music and festivities. We even thought that perhaps it wasn’t such a bad thing that the graffiti was spoiled, as it led to such a great event to restore it.

Four months later, an X sign appeared on the image of the girl in the graffiti. It wasn’t just a simple act of vandalism; someone deliberately marked an X on the image of the girl, not the boy. This time, we decided to act differently. For the next International Girl Child Day on October 11, 2022, we made T-shirts with the sign “Education is a girl’s treasure,” invited representatives of the officials, and restored the graffiti in front of their eyes. Involving authority worked for a while.

Later, eight months on, we had a study visit of schoolchildren from Baku to Mingachevir. When we showed them the graffiti, we noticed some men walking around and were irritated by our actions.

Two days later, the graffiti was completely erased, and Huseyn’s Javid slogan was overlaid with “Bir qızın namusdur zinnəti” – “The treasure of the girl is her dignity”.

“It is like the loss of a very dear person. I cried a lot when it got erased,” said a 16-year-old community member to me.

We decided to find the person who erased it. The person didn’t hide away; he was a former military officer. He claimed that what we were doing was not ethical and that with these writings, we were spreading immorality.

“Have you seen girls who go to school? They are all dressed very provocatively. What we write is against Islam,” he said.

When we mentioned that these were the words of a famous writer, he accused him of being anti-Islamic.

Another member of our community center, 19-year-old Aytaj Meherremli, remembers the brief meeting with the man who erased the graffiti.

“It was very hard to face and talk with him about it. He claimed that he was religious, but he didn’t know Islam well. He convinced people around him that an educated woman is an immoral woman and told us that by restoring this picture we spread immorality. He said that the treasure of the girl could only be her namus (dignity). He even threatened me and said that only if we wrote there – ‘One girl’s treasure is her namus’ – he wouldn’t touch the writing. He and the people around him are one of the reasons we don’t have enough people from the settlement joining our activities.”

For another community member, 38-year-old Laman Aliyeva, it was a sign of gender equality, support, and promotion of girls’ education.

“And now it is gone,” she said.

We plan to continue our work, but we are not sure how much we will be able to change minds with our actions. But one thing is certain: the story of the graffiti is not over yet.