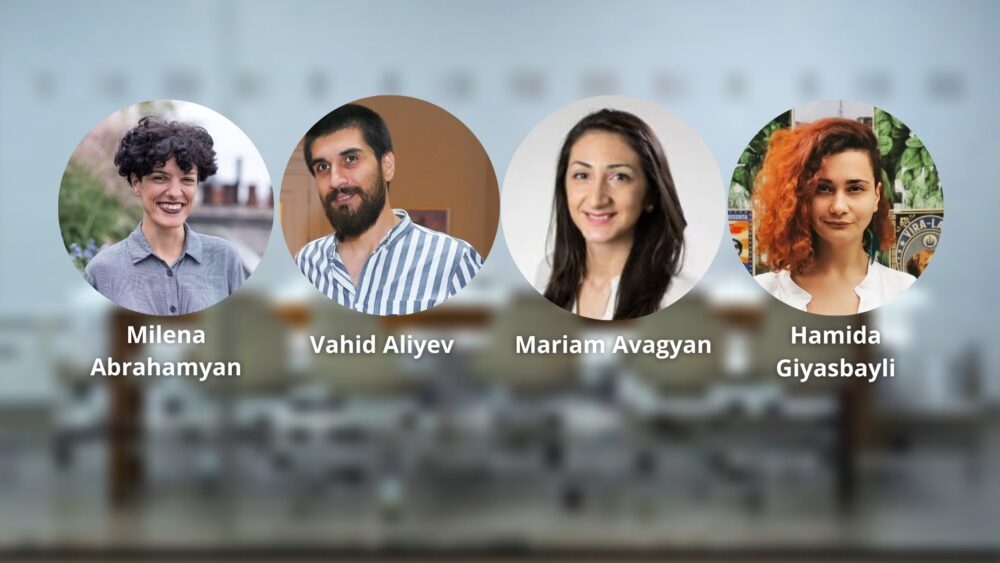

Caucasus Edition: Journal of Conflict Transformation hosted the third webinar as part of the “New War and Peace” series. “The Gendered Face of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict” was held a day after March 8, International Women’s Day. It brought together four activists and researchers from Armenia and Azerbaijan to speak about the role of gender discourses in the Nagorno Karabakh conflict and the effects of the war last year had on women and men.

The Gendered Effects of the Nagorno Karabakh War

Wars have both a physical and psychological impact on men and women. The physical impact, such as injury and the sacrifice of life are widely recognized. The psychological trauma that survivors experience could also lead to tragic consequences, but is often seen as unimportant. According to Hamida Giyasbayli, an Azerbaijani peacebuilder and a staff writer for OC Media, since the end of the Second Karabakh War, not a week goes by without a suicide by a veteran. The Azerbaijani government has set up a hotline for psychological aid, however, the expectations that society places on men to be strong and unbreakable soldiers often makes it hard for them to reach out for help.

Many women who lost family members to the war, face psychological trauma and simultaneously experience poverty and other challenges in sustaining their families. According to Mariam Avagyan, the country director at Kooyrigs in Armenia, women whose families lost a breadwinner to the war are faced with the sudden need to provide for their children. Many of these women, however, are not equipped to do that because the patriarchal culture discouraged them from building a career. The panelists from both Armenia and Azerbaijan acknowledged this to be a shared problem. Giyasbayli mentioned that the destroyed infrastructure in many post-war communities makes it particularly difficult for women, many of whom lack education or professional resume, to financially provide for their families.

The panelists also stressed that following the war, the incidences of domestic violence have increased both in Azerbaijan and Armenia. According to Avagyan, the Armenian government has been dismissive of the problem. Armenia is facing an existential crisis, so the expectation is that the family unit acts as a pillar of society. If a woman speaks out about domestic violence it is seen as a challenge to the family and, therefore, a challenge to the nation and its survival. For this reason, the dominant attitude has been that women are expected to tolerate domestic violence.

Avagyan also stressed that for more than a month, women carried on with life in bunkers, gave birth in bunkers, and raised children in bunkers. When discussing the future, she argued, it is necessary to address the traumas that violence inflicted and reparations and restitution of rights for those who suffered from the war.

The co-moderator of the webinar, Philip Gamaghelyan, agreed that addressing the trauma of the war should be an integral part of the peace process. He noted that the traumas of the First Karabakh War and the harm done to the civilian populations were never addressed. The atrocities perpetrated during that war were politicized and used to portray the other side as barbaric without ever becoming the focus of the peace process. He stressed the need for making the transitional justice integral to the new phase of the peace process.

Why talk about gender and conflict?

The moderators shared that in the run-up to the event, some audience members reached out to the organizers suggesting that they would prefer to hear instead about the politics and geopolitics of the conflict instead of gender. Others expressed their displeasure with the presumed focus of the webinar on the impact of the war on women, while the main victims of the war were the men who lost their lives. Gamaghelyan, outlined the rationale for organizing a webinar on the interlinks between gender and conflict. He pointed out that most webinars in the series were, indeed, focused on politics and geopolitics of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. At the same time, the conflict has entered every sphere of life: education, media, economy, environment, and gender. These are, consequently, topics worthy of consideration and discussion. All parts of our identities, including our gender identities, are severely affected by the logic of the conflict that sees men as soldiers and women as supporters of soldiers. These expectations are not temporary. The conflict has continued for three decades. There is no end in sight. These are the identities that generations of Azerbaijani and Armenian men and women carry for all of their lives. The co-moderator further pointed out that the term “gender” is mistakenly perceived as synonymous with women, while the webinar covered the impact of the conflict on men as well. Conflict affects men and women differently. Thousands of men have sacrificed their lives. This is an unspeakable tragedy and an effective peace process should be put in place immediately so all further loss of life is averted. The suffering of women as a result of the war, however, is less acknowledged and is often considered secondary. As a result, women who suffered from the conflict do not receive support from the society at large.

Addressing the same question, Milena Abrahamyan, an activist and a researcher of peace, gender & conflict, explained that the discourses of gender and conflict are interlinked. One’s own side is portrayed as a strong masculine hero, while the enemy is always portrayed as a hated female, violence against whom is justified. Vahid Aliyev, an activist and researcher of queer history, pointed out that the conflict discourse creates categories of citizens who lives are seen as non-valuable and not grievable. Abrahamyan agreed, arguing that within a conflict context, anyone who does not conform to traditional gender roles is seen as an internal enemy.

Giyasbayli pointed out that women are also excluded from the official peace process. In nearly 30 years of official negotiations, neither the Armenian and Azerbaijani government nor the international mediators had female representation. Giyasbayli disputed the stereotype that women are inherently more peaceful and stressed that she did not expect to see any immediate breakthrough in the peace process if women were involved. However, women represent half of the population and are impacted by the war in different ways than men, the speaker concluded. Their presence and voices at the negotiations table is a necessity.