It was a hot July day when I stepped inside my uncle’s house to cool off. The thick-walled, dark house had once been a barn. My cousin emerged from a room with a long, cylindrical white piece of cloth twisted around his nose, a string dangling from the end.

I asked him what it was.

“It’s for my nosebleeds,” he said.

“They always give these out in the aid boxes.”

That summer, he wore that cylindrical thing constantly. It became a familiar sight, always perched on the tip of his nose.

Later, I learned what it really was: a tampon.

In 1993, we became internally displaced persons (IDPs). Both of my parents had to leave their homes in Aghdam, one of the seven regions that came under the control of Armenian forces in 1993, during the first Nagorno-Karabakh war and move across different parts of Azerbaijan in search of a new place to live. After much displacement, we eventually settled in Baku, where I grew up.

Our family wasn’t wealthy. My parents had spent everything they had, either in Karabakh or along the road. We mostly ate simple, traditional meals with lots of fried potatoes and onions.

Sometimes, though, we had new items on the table: canned beef or powdered milk. I loved the smell of the powdered milk. My mother said these foods came from donations.

One day, we received a blanket with black and yellow stripes. Unlike the wool blankets from my mother’s dowry, this one had a zipper along the edge and kept us very warm. When I was seven or eight, I loved wrapping it around my waist like a princess dress and looking at myself in the mirror. My mother still uses that blanket today.

The word “donation” referred to boxes filled with food, hygiene items, medical supplies, and other essentials distributed for years to people displaced from Karabakh.

In the 1990s, aid boxes arrived in Azerbaijan from various organizations and organizations like, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Germany. The source of the aid often depended on the region. Because IDPs were scattered across the country, not everyone received the same aid, and the contents varied.

Since we settled in Baku, we received very little. My parents couldn’t afford to wait in long lines or travel to other districts just for an aid box. They had to work, and time meant money.

But dozens of our relatives living in other regions received aid boxes regularly. Over the years, I heard many stories - some funny, some frustrating - about these mysterious parcels.

When I decided to write this piece, I reached out to many of my relatives to hear their memories. I was too young at the time to remember the details myself. Now, as I listen and learn, I feel both nostalgic and amused.

Preservatives, Scrambled Egg Powder, and Cookies

'' We lived in Ismayilli,( 170 km away from Baku) and aid arrived monthly. We always knew when it was coming and were excited. They brought not only staples like oil, rice, pasta, peas, flour, and sugar - but also toothpaste, brushes, and creams we didn’t recognize. Someone who could read the labels said it was face cream, so we used it that way. They also gave us powdered scrambled eggs and mashed potatoes. At first, we didn’t know what they were until a guest explained. The texture was strange, but the taste was good.

Funny story: they also sent preservatives. We didn’t understand what they were, so we used them as toys. We’d fill them with water and watch them swell. My father got angry once, but I secretly took one to the spring and watched it fill with water until it burst.

One year, we received a tent with multiple layers. My mother cut it up and made mattresses. When our goats had twins and didn’t have enough milk, we mixed dried milk with warm water and fed the baby goats using bottles.

We thought the government gave us this aid. As children, we noticed only we received it, and I once asked a neighbor why. She said, ‘You’re the arrivals - that’s why you get it.’

But the best part was the cookies. Until 1998, they gave us square cookies in clear plastic packaging, 10 or 20 in each pack. Maybe because I was a child, they seemed endless. They were vanilla-flavored and delicious. We ate them slowly to make them last.

Sometimes, cookies came in an iron tin that was hard to open. We waited for our father to come home and open it. He would give us one each so we’d have enough for the next day. Those moments brought us joy.

At that time, we couldn’t buy cookies. We had no money for sweets. There was a shop nearby where we traded lollipops for cookies, but when they ran out, we started counting the days until the next aid box arrived. When it came, it felt like a holiday. We’d dump the box in the middle of the room and examine each item with curiosity.

Doctors came too. A doctor and nurse arrived in a Niva car and treated people for hours. Veterinarians came to check animals and give vaccinations. This continued until around 2000.

The aid was very helpful, though in the later years the contents often seemed useless. My father, for instance, fed the beans to the chickens because they weren’t edible.''

Dutch Cheese

“We lived in Jalilabad ( 200 km away from Baku) for a while. The aid there once included Dutch cheese. We didn’t like it at all - it was so unfamiliar. We gave it away, not realizing it was expensive. They also brought pumpkin jam, which really surprised us.

But overall, the aid was good. They even gave us petrol. Once, we received these thick, plain-looking things that we thought were toffees. But they turned out to be salty! They were Galina Blanca bouillon cubes.''

Meatless Bozbash

'' In Baku, we didn’t get much aid. But in Binagadi, each person received 10 kg of flour, 1 kg of wheat, and 3 liters of oil - though we didn’t know what kind it was. There was also chickpeas, red beans, sausage, and canned beef, plus cookies, pasta, and powdered milk.

When we didn’t have meat, I made bozbash with chickpeas or bean soup. I made powdered mashed potatoes for the children, and they ate them. Sometimes we fried the sausages and added eggs. ''

Soap and Lice Medicine

“The contents of the aid boxes varied depending on the region. We lived in both Ganja and Barda at different times. Some boxes contained flour, sugar, oil, and canned meat. Humana, a company, sent particularly good baby food and canned meat. Sometimes we received toys, like a pretend cooking set.

One month, we received hygiene items and soap - but the soap caused lice outbreaks! The next month, they sent lice medicine.

Not all aid was helpful. Some flour was spoiled - contaminated during transport. Pregnant women were placed on a separate list and received better aid, like baby food and clothes. Some people pretended to be pregnant just to receive these.

There was also medical help, but it wasn’t very effective. One doctor treated everyone with the same medicine, regardless of the issue. People took it anyway - because it was just free. ''

Natural Orange Juice

'' I first saw aid boxes in Imishli. A truck arrived and people said it was from the Arabs. The boxes had towels, blankets, clothes, soap, toiletries. It was chaos - people stepping over each other to get to them.

One item was natural orange juice. It even had bits of peel in it. At first, we didn’t like the taste and made fun of the name. But eventually, we came to enjoy it.

Because my father was a martyr, the Arabs took me to Baku and paid all my expenses. They even gave me money, which I brought home to my mother.

Looking back, those aid boxes were more than just supplies. They brought joy, confusion, and sometimes laughter. Though the aid eventually stopped, the stories it left behind remain. What began as a box of essentials became a box of unexpected discoveries - memories we’ll always carry with us. ''

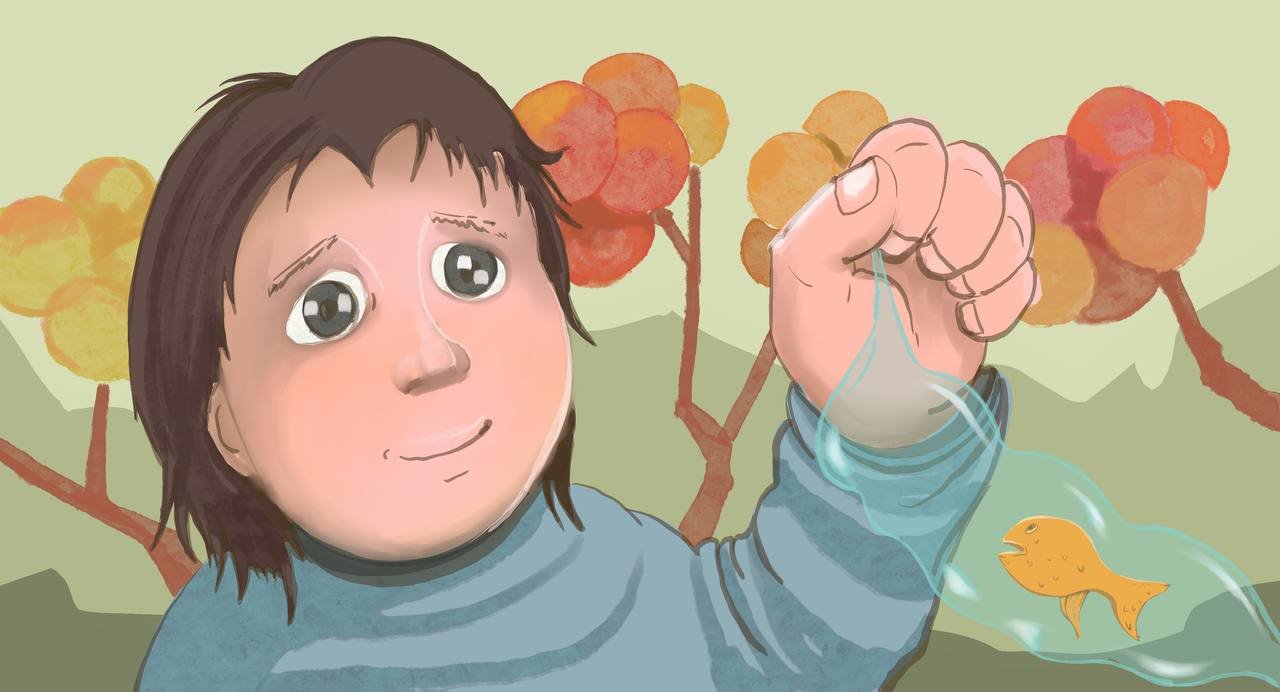

Illustrations: Magerram Zeynalov