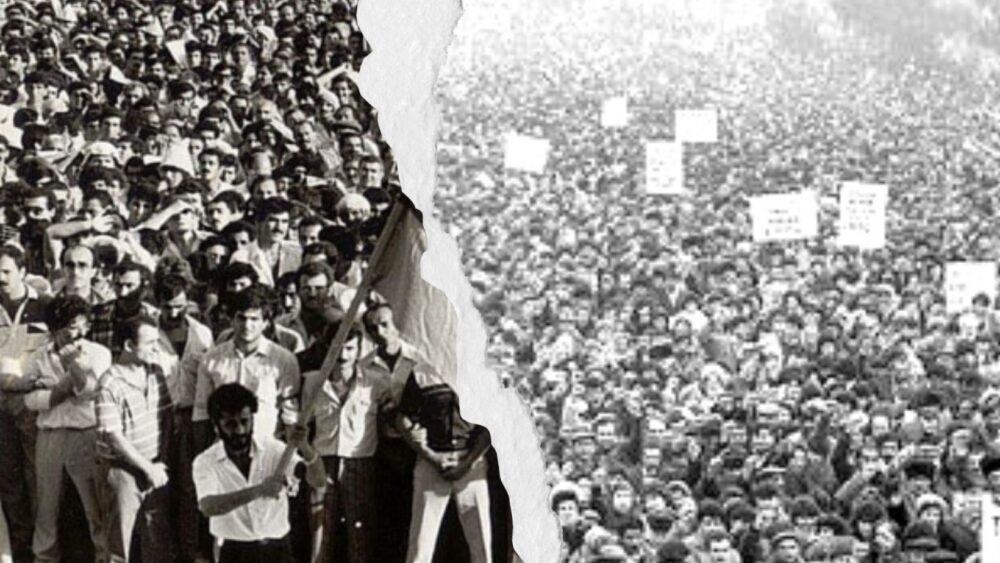

The article presents a discursive analysis of the onset of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, from the beginning of the independence movements of Armenia and Azerbaijan in the late 1980s through the presidencies of Heydar Aliyev and Robert Kocharyan. The analysis traces the formation of new national identities in Armenia and Azerbaijan in opposition to each other, the consolidation of antagonism, and the importance of these developments for today’s context.

Introduction

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia is one of the most long-lasting conflicts in post-Soviet space. The disputed Armenian-inhabited Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO), created in 1923 by Bolsheviks within the borders of Soviet Azerbaijan as an autonomous region had been an object of tension between the two republics already during Soviet times. In different periods, Armenian public intellectuals and party officials made appeals to the central government in Moscow to attach the region to Armenia. The tensions had only intensified during the 1970s between the authorities in Baku and the oblast’s leadership over political-economic issues (De Waal 2003, 138). From November 1987 to February 1988, representatives from NKAO visited Moscow three times to lobby for their cause. The increasingly weak central government in Moscow did not meet their demand, setting the groundwork for the outbreak of the first war in Nagorno-Karabakh, officially frozen in 1994.

The outbreak of the conflict in 1988 and inter-communal violence, mainly manifested in deadly pogroms, impacted the emergence of national movements and identities in both newly emerging independent countries. This article analyses the emergence of independence movements in Armenia and Azerbaijan in 1988, their further development, and their impact on both societies during the first years of independence. The object of our interest is the discourses of these movements and the reconstruction of national identities amidst the weakened socialist system. Our discursive reading of the independence movements focuses on events and their impacts, demands, subject positions, and ethical level. We explore their development and trace their antagonism, including the specific features of this process.

From Environmental Concerns to Popular Movements

On February 18, 1988, an environmental protest broke out in Yerevan. At the time, Yerevan was one of the most polluted cities in the Soviet Union. The initial demand of the protesters was the improvement of the condition of Lake Sevan, concerns about the risks associated with the Metsamor Nuclear Power Station and the Nairit Chemical Plant, and other environmental issues. According to Thomas De Waal, in the first few days of the protests, there were very few people present, but by February 24, the number of people had reached close to a million (2003, 23). The participation of large segments of society had transformed the demands of the protest. The people had started chanting “Karabakh” and “Miatsum,” and soon the speakers and the political leaders were laying out the map they envisioned for uniting the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) with Soviet Armenia.

During the protests, the Soviet Union stood by its non-unification stance. Karen Demirchian, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia, passed on Moscow’s stance to the protestors, articulating by saying “the friendship of nations is our priceless wealth – the guarantee of the future developments of the Armenian people in the family of Soviet brotherly nations.” (De Waal 2003, 25). The Soviet leadership attempted to rally people around the official ideology, diverting the protest discourse from becoming antagonistic. Amid these ongoing demonstrations, the ethnic Armenian minority in the Azerbaijani town of Sumgait faced pogroms that began on February 27 and lasted until the end of the month. The Sumgait pogrom predetermined the future of demonstrations in Armenia.

The protesters and political leaders of the movement were initially operating inside the Soviet system and its official discourse. Still, the re-articulation of national identity was starting to emerge. On June 11, 1988, the future first president of the Republic of Armenia, Levon Ter-Petrosyan, publicly presented the demands to be given to Moscow during the upcoming Supreme Soviet meeting (YouTube 2020e). He began his speech by listing injustices committed against the Armenian population in NKAO and articulated six demands. The primary demand was as illegal the recognition of the 1921 decision of the Caucasus Bureau to create the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) and place it under Soviet Azerbaijan’s jurisdiction. Ter-Petrosyan added that this decision had made positive relations between the Armenian and Azerbaijani nations impossible. Ter-Petrosyan also spoke of the fate of the Armenians of Nakhichevan and injustices done to the Armenians in different parts of Azerbaijan, equalizing those injustices with the term “genocide.” Additionally, he called on the Supreme Soviet to recognize the Armenian Genocide.

The first demonstrations in Azerbaijan occurred in November 1988, when the rumors about the upcoming plans to cut down the Topkhana forest and build an aluminum plant near the city of Shusha/Shushi in Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) had spread in Baku (De Waal 2003, 83). The rumors took place against a backdrop of protests in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, causing widespread anxieties and defining the future and ideological basis of the independence movement in Azerbaijan. Shusha/Shushi was of symbolic importance for Azerbaijanis, unlike other parts of the Armenian-inhabited regions of Nagorno-Karabakh. The mostly Azerbaijani-inhabited Shusha/Shushi was perceived as “the birthplace of their musicians and poets” (De Waal 2003, 30) – a narrative supported by the Soviet ideologues in the construction process of Soviet Azerbaijani national identity.

The alleged plans to cut trees in the Topkhana forest were less about environmental concerns and more about the old ethnic tensions in Nagorno-Karabakh and the emerging nationalist imaginary. In nationalist discourse, ecological objects (e.g., forests, soil, mountains, seas, animals) in the territory of the national ‘Self’ are framed as ‘the wealth of the nation.’ Consequently, the damage to nature, if committed by members of the other communities, is conceived as an act of humiliation. In the case of the Topkhana forest, the alleged plans led to massive demonstrations in downtown Baku with the demand to stop the destruction.

In Laclau’s theory of populism (2005), social demands play a vital role in forming collective identities and social movements. Social demands, be they claims or requests, are the fundamental units of analysis of social movements. When addressed to the locus of power while remaining unfulfilled, social movements can articulate these collective frustrations and form a discourse and identity centered around these unsatisfied demands. Laclau differentiates between democratic and popular demands. In the first case, a concrete, unfulfilled social demand creates a most likely small movement based on an isolated claim. In contrast, in the second case, numerous demands are united around a broader social subjectivity (Laclau 2005, 74) – such as with the re-articulation of the nation. In both Azerbaijan and Armenia, the first demands emerged from environmental and cultural-historical concerns. They were articulated as “democratic demands” within the existing system without constructing antagonistic frontiers between communities. However, these first demonstrations were enough to disrupt the social order that was not accustomed to mass protests: the accumulation of unsatisfied demands and social anxiety transformed the protests into nationalist populist movements. In both contexts, the movements produced affectively strong slogans that assured the mobilization of the masses.

In the newly forming re-articulation of Armenian national identity, the affectively laden signifier “Armenian Genocide” is seen as a red thread moving through the narrative of the events leading up to the first war in Nagorno-Karabakh. In the minds of many Armenians, Nagorno-Karabakh and formerly Armenian-populated places in modern Turkey, which were emptied of Armenians after the genocide, are connected because of a similar fate. Poetry is a powerful tool for the re-articulation of such signifiers that lead to the affective experience of collective memory. One of the prominent writer-activists on the frontlines of the movement, Silva Kaputikyan, wrote in her poem:

When they say “fifteen”

I remember a “year”

When they say “mountainous”

I remember “Karabakh”

They have their own flow in me,

Words are hidden from me,

They say “justice”

I remember my orphan, Van!

Kaputikyan’s parents were Armenians who had escaped from Van because of the genocide. For many, the removal of Armenians from many towns of modern-day Turkey had a direct association with the events surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh, constructing a horrific scenario: if the Armenian nation did not protect Karabakh now, it would share the fate of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. Kaputikyan’s poem represents the associative series that represents the impacting trauma. In the poem, “Karabakh” plays the role of the object of desire, while “Van” is associated with the traumatic past.

Similarly, another author, Gurgen Gabrielyan, wrote in one of his poems:

Each of you is a new Gevorg Chaush,

[…]

Go forth to battle with the holy flag

So that the nation and homeland live freely

For the union of the brave son and mother

For the sake of Artsakh and all Armenians

In this poem, Gabrielyan sacralizes the movement and connects it to past injustices, arguing that the nation once again needs heroes as it had before. Comparing the participants to the historical national hero Gevorg Chaush, the poet conceives the protesters as protagonists who would save Artsakh and all Armenians. Central to this narrative is that history is repeating itself and Armenians must be united in the face of the enemy that is not new but has come again from the past. In a popular song written and performed at the beginning of the 1988 Movement, the singer urges Armenians to unite for Artsakh because “[the] old enemy has not rested; he wants to massacre the Armenians again.” Thus, national unity became the ethos of the movement. In addition to the Armenian Genocide, the song also mentions the example of Nakhichevan and mentions how its Armenian population has been forced out. With this narrative as the driving force, “Miatsum” became the central demand of the movement because it was seen as the only way to guarantee security for the ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh.

The movement continued at such a pace that Moscow or even local political leadership could not keep up with it. The peaceful beginning of the movement quickly transformed into antagonism. As the collapse of the Soviet regime neared, the reshaping of the identities of its republics accelerated the process. Some political leaders were starting to see solutions outside of the Soviet system and a split occurred within the movement. In an interview given to Thomas De Waal, Ter-Petrosyan noted that at the beginning, the first leaders of the Karabakh Committee did not aim for the independence of Armenia and this is where the split among the leadership took place: “They thought that the Karabakh question had to be solved, by using the Soviet system. And we understood that this system would never solve the Karabakh issue and that the reverse was true: you had to change the system to resolve this problem.” (2003, 57). In other words, the weakening of the Soviet state machine, which was not capable of meeting these political demands, had transformed the movement into an anti-systemic one.

While the events in the Topkhana forest were the catalyst of the mass demonstrations in Baku, the wave of ethnic Azerbaijani refugees from southern Armenia settling in Azerbaijan in early 1988 had already caused widespread anger and anxieties that damaged the Soviet Azerbaijani identity. According to their stories, in the Armenian cities of Meghri and Kapan, these refugees faced unprecedented violence and were forced to flee. Many settled in the industrial city of Sumgait (De Waal 2003, 18–19). The case still raises many questions, but what is clear is that the outbreak of violence resulted in the first wave of Azerbaijani refugees. The first anti-Armenian pogrom that took place in February 1988, known as the Sumgait pogroms, lasted for three days and resulted in the death of dozens of ethnic Armenians. Later, Deputy General Procurator Katushev described the Sumgait events as “connected in the closest way with the events in Nagorno-Karabakh” (Beissinger 2002, 298). De Waal’s description of the Sumgait tragedy as “the first violent fission of a ‘Soviet’ identity” (2003, 37) could also be described as the first widely known and shocking incident in the late 1980s in the Soviet Union that involved bloody inter-ethnic clashes that undermined the ongoing Perestroika policy. Later, almost 400 people were arrested and 84 active participants faced different criminal charges. In both societies, the Sumgait pogrom had enormously intensified nationalistic sentiments and mobilization. For many Azerbaijanis, as we will see later, the case was not that straightforward.

Counter-hegemonic movements offer their own narratives and myths that are meant to help people through the crisis and overcome instability. Thus, the set of material events in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh and the following Sumgait pogroms led to the emergence of the Meydan Movement (“Square” from the name of Lenin/Freedom Square, situated in the city center, where demonstrations took place) in Azerbaijan. Similar to Armenia’s mass movement, at its first stages, the Meydan Movement did not demand independence from the Soviet Union but acted within the existing late socialist order. The movement was led by the mostly right-wing Popular Front of Azerbaijan (PFA). The leaders of the Meydan Movement, such as future president and pan-Turkist intellectual Abulfaz Elchibey, nationalist poet Khalil Rza Uluturk, and populist trade-unionist orator Nemat Panahov, effectively mobilized people around anti-Armenian sentiments.

In a video from late 1988, Abulfaz Elchibey (YouTube 2020c), surrounded by flags of both the Soviet and Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan, blamed the central government in Moscow for weakness regarding the pogrom of ethnic Azerbaijanis in Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital, Stepanakert: “The problem is in the center, Moscow, who does not command in a proper way. […] They should send an army to Stepanakert to bring order back. But they are not able to do that, and they do not want to do it.” Later in the same speech, Elchibey threatens the central government that Azerbaijani mothers will not “send their sons to the army service,” adding that the three defendants of the Sumgait pogroms should be tried by the Azerbaijani authorities (“It is a matter of Azerbaijan,” he argued) and not in Moscow.

Referring to the events in Sumgait, pan-Turkist poet Sabir Rustamkhanli, another leading figure of the Meydan Movement, claimed that the pogroms “were organized by powers from abroad, by Dashnaks, [as a part of] their cunning plans,” articulating a conspiracy narrative that would prove that “[these events] should not smear our nation.” (YouTube 2020d) Nationalist historian Ziya Buniatov promoted an even wilder conspiracy theory regarding the Sumgait tragedy. According to his version, which is widely accepted in Azerbaijani society, Armenians organized pogroms against themselves in order to discredit Azerbaijanis at the international level (De Waal 2003, 42).

Following Rustamkhanli, Azerbaijani intellectual and poet Bakhtiyar Vahabzade mentions “Lenin’s national policy of brotherhood of nations” and demanded autonomy for ethnic Azerbaijanis from the authorities of the Armenian SSR considering their “current miserable condition.” (YouTube 2020d). The rhetorical difference between the softer Vahabzade and hardline pan-Turkist orators proves that the Meydan Movement was not homogeneous: at least in the beginning, along with proponents of antagonistic nationalism, there were supporters of official Soviet ideology. Similar to Armenia, in Azerbaijan, too, the antagonistic interpretation of national identity was not hegemonic. Rather, the blamed ‘Others’ were either central Soviet or local governments or outside forces. Articulated in this way, the discourses of both movements did not reject the official discourse of internationalism and its relevant narratives, such as the friendship of nations. However, with the weakening of the central government, the antagonistic nationalist wings in both movements soon prevailed.

How can we trace these developments in Azerbaijan? In his seminal work, “Meydan Movement: 4 Years, 4 Months,” Adalat Tahirzade recalls famous slogans of the movement. In the beginning, people used to chant “Long live Lenin’s National Policy,” “the USSR is one country, we will not allow its division,” and “We are not nationalists, we are internationalists.” With the naturalization of nationalistic ideas, these socialist slogans were replaced by “Long live independent Azerbaijan”, “We have two eyes – one is Baku, the second is Tabriz!” and “Long live democracy!” One of the most uniting and representative slogans was “We will die but will never give up Karabakh.” (Tahirzadə 2021).

The nationalist social imaginary sacralized the meaning of Karabakh as an object of national desire. In a typically emotional speech, populist poet Khalil Rza Uluturk described Karabakh as “Azerbaijan’s temple, Azerbaijan’s artery, Azerbaijan’s heart,” (YouTube 2019) thereby essentializing it as naturally and spiritually belonging to Azerbaijan, thereby opposing Armenia’s claims and giving to Karabakh an objective value. Sabir Rustamkhanli, in a rally in 1988, called for an urgent international symposium to “prove that Karabakh historically belongs to Azerbaijan.” (YouTube 2021).

Claims, structurally similar to the discourse of Miatsum, were also articulated in Azerbaijan though these ideas were rather anecdotical and not consistent, unlike Elchibey’s later irredentist “Whole Azerbaijan” that targeted Iranian Azerbaijan. In Tahirzade’s book, we can find some evidence. In an early, pre-square demonstration in May 1988, Khalil Rza declared: “Treason against Azerbaijan has been going on for almost two hundred years. Azerbaijan is not divided into two, but into two hundred places. […] Derbend, Borchali, Goycha, Zangezur… were torn from Azerbaijan. We demand autonomy for Azerbaijani Turks living in RSFSR, Armenia, Georgia!,” (Tahirzadə 2021). Thus, the chain of equivalence of “lost lands” included not only the territory in Western Armenia (Zangezur and Goycha) but also Azerbaijani-inhabited areas in Georgia and Derbend. The loss of these territories was conceived as an historical injustice and the result of treason.

Through different discursive means (pseudo-historical narratives, populist rhetorical devices, and poetry) the early discourse of antagonistic Azerbaijani nationalism established a discursive relation of representation between the signifiers ‘Azerbaijani Turks’ (the nodal point of the national ‘Self,’” or the representative) and ‘Karabakh’ (the signifier of desire, the represented). In such a domain, the Armenian discursive-material presence in Nagorno-Karabakh was excluded and silenced.

The following events accelerated the antagonization of discourses and created fertile soil for its naturalization in Azerbaijan. Between January 13-15, 1990, radical nationalists committed even bloodier pogroms, assassinating approximately 90 ethnic Armenians in Baku. After that, the Soviet Interior Ministry invaded the city on January 20 and more than 130 ethnic Azerbaijanis were killed (De Waal 2003, 89). The events of “Black January” re-territorialized material violence from Karabakh to Baku and changed the status of the central Soviet government in Moscow from the ‘distrusted’ Other to the ‘enemy’ Other. Consequently, “Black January” strengthened the idea of independence from Moscow. The cultural trauma of “Black January,” distributed through the horrific photographic and video materials among members of the national community, also changed the perception of the Self: while in antagonism with the Armenian Other (other-perpetrator) only the ethnic Azerbaijanis in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh were victims, in the case of the intervention of Moscow, all the ‘honest citizens’ of the nation were articulated as victims. For many Azerbaijanis, “Black January” has become the beginning of independence and “the most important national mourning day,” the source of “grief and pride” (Militz and Schurr 2016, 58).

The newborn political leadership of Armenia went on to deepen the divide between the ‘Us’ (Armenia) and ‘Them’ (the Soviet leadership). A new political party was born, aptly named the Armenian Pan-National Movement. Ter-Petrosyan declared that the Sumgait and Baku pogroms showed that Moscow was not interested in protecting Armenians (Barseghyan 2003, 12), concluding that Armenia had to gain its national independence. On September 21, 1991, Armenians voted to secede from the Soviet Union. In the absence of the locus of power in Moscow, this distrusted Other, another Other, was developed: the newly independent Republic of Azerbaijan.

Thus, we are confronted with a set of subject positions in the dominant discourses of the Meydan and 88 Movements: clearly, there is the homogenized national Self – those who identify with the nodal point of the nation – and the subject position of the other-victim: the ethnic Azerbaijani minority in Armenia and ethnic Armenian minority in Azerbaijan. These Others, despite differences, are closely related to the so-called national selves. There are different Others: the distrusted central government in Moscow and incompetent local governments; and Armenia and Azerbaijan, each increasingly turning from an entity distrusted into an enemy.

The ethical basis of both movements was constructed around a set of nationalist empty signifiers and the object of desire. In both cases ‘Karabakh’ was the primary object, which had been essentialized as an organic part of the national communities. The commonly shared spaces and the very possibility of future togetherness were excluded from nationalist imaginaries. This exclusion had resulted in horrifying pogroms and their de-facto negation through conspiracy theories. It is also worth understanding the ethos of movements: neither side glorified offensive violence or explicitly called for it. Instead, both sides expressed themselves as victims of the perpetuator-other. In the case of Azerbaijan, the pan-Turkist imaginary re-articulated the signifier of the Self as Azerbaijani Turks. In Armenia, the homogenized Self included the Armenians of Armenia and NKAO.

The war in Karabakh not only caused the emergence but also ended the political careers of many Meydan Movement leaders, including the short presidency of Abulfaz Elchibey, who came to power in 1992. In early April 1993, Azerbaijani-inhabited Kelbajar, a town outside Nagorno-Karabakh, was captured by Armenian forces, causing shock and accelerating the collapse of the government in Baku.

After the First Nagorno-Karabakh War

After the war, the national identity formation process continued similarly in Armenia. The more liberal Levon Ter-Petrosyan was forced to resign and in his place came the former president of Nagorno-Karabakh, Robert Kocharyan. Under Kocharyan’s leadership, Armenian identity expanded to contain the diaspora and Nagorno-Karabakh. As Kocharyan himself put it, “It is obvious that at present Armenia, Karabagh, and the Diaspora are facing significant national issues that require urgent solutions. And it is much more obvious that these problems can be solved only if our three national attributes cooperate closely and permanently, led by national unity as the criteria.” (Barseghyan 2003, 15). In this discourse, Armenia becomes the “Motherland of all Armenians” with each point of the trinity feeding off the others in the service of unity (Barseghyan 2003, 17).

During Heydar Aliyev’s presidency (1993-2003) in Azerbaijan, the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh was a major issue in society. The war ended in 1994 when both sides signed the Bishkek protocols and achieved a ceasefire, leaving the Azerbaijani side wounded. For many Azerbaijanis, the truce was humiliating.

In his 1999 speech, Heydar Aliyev mentioned that the 1923 decision to establish autonomy in Nagorno-Karabakh even within the borders of the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic was unjust: “I have led Azerbaijan for 14 years. I know very well the history of the establishment of the Nagorno-Karabakh oblast in 1923. The granting of autonomy to Nagorno-Karabakh in 1923 was a disaster for Azerbaijan. … That autonomy granted in 1923 is a bomb planted inside Azerbaijan. It should have exploded at some point.” (YouTube 2020b). Importantly, Heydar Aliyev’s regime, despite its semi-authoritarian tendencies, did not rely on pan-Turkism and fierce nationalism as the previous Popular Front government did. However, the government remained ambiguous about the rights of Armenians over Nagorno-Karabakh following the societal consensus and articulated the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan as the only solution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, though Aliyev accepted the need for “mutual compromises” (Brown 2004, 583).

In this regard, the friendly meeting between Heydar Aliyev and Robert Kocharyan in the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan is noteworthy. Both presidents agreed on the importance of compromises and the necessity of communication. Simultaneously, direct contact between the two countries’ civil societies and intelligentsia was possible and not prohibited, continuing until the 2010s (Ghaplanyan 2010), when Azerbaijan drifted to full-blown authoritarianism.

The picture was quite different in Azerbaijani popular discourses. On the level of pop culture, the nationalistic rap song “Either Karabakh or Death” (1999) by the iconic band Dayirman is representative: “Young, elder, women, girls perish endless / Arms cut, eyes gouged out / Their cries spreading around like waves / The grave of a martyr is now more than one.” The rap calls for “jihad” and stresses the Turkic identity of the nation. The video footage from the Khojaly massacre is used in the song’s music video and was frequently shown on the populist-nationalist ANS TV channel, thus having an enormous impact on viewers. A 2001 poem by Baba Punhan, a conservative Shia poet from the outskirts of Baku, similarly demonstrates how sacralized Nagorno-Karabakh has become and how its loss has been painful. Looking backward from an imaginary future, Punhan wrote:

Let the black land swallow me if Karabakh goes

I have no right to be alive if Karabakh goes

How many girls and wives fell into captivity?

Write a defector to my grave if Karabakh goes.

[…]

If we play with Armenians again,

They will demand more if Karabakh goes.(YouTube 2013).

It is clear to the reader of the poem that Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent territories are already “gone,” which means the nation has already experienced the loss. By mentioning “girls and wives” and “young, elder, women, girls,” Punhan and Dayirman strengthen the feeling of disgrace and victimhood, pushing the Azerbaijani reader to re-experience the trauma of loss and booster the demand for ressentiment. During Heydar Aliyev’s reign, Karabakh had become a sacred land and the need for revenge had intensified through the demonstration of various war crimes allegedly committed by Armenians during the war. Simultaneously, alternative discussions (such as the pogroms committed by Azerbaijanis) were excluded from public discourses while conspiracy theories about pogroms were normalized and accepted.

In popular discourse, the image of the enemy was constructed as evil, cunning, and non-negotiable. The latter questioned the attempts to solve the conflict by employing diplomacy. In the popular TV show Qulp, the sarcastic ashik Yadigar sings and dances:

The Lisbon summit deceives us,

We do not deserve to be reconciled with the enemy,

Future generations will spit in our faces,

Where are my honor and zeal?!

When is it time for me to return to my lands? When is it time?! (YouTube 2020a).

The OSCE Lisbon Summit took place in December 1996, during which the offer was for Nagorno-Karabakh to have the status of the highest level of self-government within the borders of Azerbaijan. The resolution supported the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and demanded the withdrawal of Armenian forces from the occupied territories near Nagorno-Karabakh (De Waal 2003, 256). While the summit was presented as Heydar Aliyev’s diplomatic victory, populist discourse questioned the very possibility of reconciliation with Armenians as an act of dishonor. While the governmental strategy was more pro-negotiations, the populist and nationalistic discourses stressed the radical difference between Azerbaijanis and Armenians, between whom no symbolic or material common spaces and values were thought to be shared.

Conclusion

The discourses of independence movements in Armenia and Azerbaijan left an indelible imprint on post-Soviet national identities in both communities. Beginning as a reaction to spreading anxieties about the fates of fellow countrymen in Armenia and Azerbaijan, the movements quickly adopted antagonistic nationalist tropes. These tropes did not include any vision of co-existing and (conflictual) togetherness. In both cases, the ‘selves’ were imagined and articulated as defenders; neither of sides accepted crimes committed by the members of their communities in near or distant past.

The absence of a discourse on ‘togetherness’ and the hegemonic interpretations that essentialized and sacralized the meaning of ‘Karabakh’ further deepened the conflict, making finding a solution all the more difficult. The eruption of violence, the dissolution of the Soviet national identity, and traumatic loss of territories all presupposed the emergence of new national myths and narratives. These new narratives were transmitted by politicians, poets, and populist leaders the independence movements. They have constituted the basis of the post-Soviet identities, embedding the sacralization of Nagorno-Karabakh.

In Azerbaijan, the loss was perceived as a national tragedy and disgrace. The necessity of the return of Karabakh by any means necessary was a consensual point of agreement between all mainstream social actors in the country, playing the role of the national ethos. While the right-wing opposition parties (the successors of the independence movement and 1992-1993 government) and popular discourse stressed the intention for ressentiment through military involvement, Heydar Aliyev’s statist government remained ambivalent, embracing constructive agonism at the international level and articulating popular antagonistic nationalistic narratives for the internal audience. In the end, Heydar Aliyev’s regime did not challenge the popularly accepted antagonistic nationalism. Neither there was a clear policy on the future of Armenian-inhabited parts of Karabakh after its ‘return.’ Nevertheless, the need for its return constituted the collective goal of the national community for the next decades.

When analyzing the outcomes of the current post-war situation in the region, and the role of nationalism and national identity in the region, specialists should consider the beginning of the conflict and the construction of national identity. Here, it is essential to be aware of not reducing antagonistic nationalism in Azerbaijan to the government and propaganda tools: in fact, the emergence and spread of an antagonistic form of nationalism derived materially from the trauma of loss and discursively from the populist discourse of the independence movement.

To put it differently, antagonistic nationalism in Azerbaijan has not only been the prerogative of the ruling regime to legitimize itself. Rather, the entire political spectrum has been inflected by this nationalism from the first years of the country’s independence. This deeply embedded antagonism has prevented the construction of alternative narratives. This would require the proliferation of the idea of shared spaces in the discourse of new progressive politicians, media initiatives, and social groups.

The widespread acceptance of conspiracy theories should be tackled in both societies. Civil societies, especially NGOs focusing on peace discourse, should touch on these seemingly uncomfortable topics. At the same time, they should produce models of spaces of togetherness while accepting the symbolic and cultural importance of Karabakh for both societies.

Bibliography

Barseghyan, Kristine. 2003. ‘Rethinking Nationhood: Post-Independence Discourse on National Identity in Armenia’. Polish Sociological Review, no. 144: 399–416.

Beissinger, Mark R. 2002. Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Cameron S. 2004. ‘Wanting to Have Their Cake and Their Neighbor’s Too: Azerbaijani Attitudes towards Karabakh and Iranian Azerbaijan’. Middle East Journal 58 (4): 576–96.

De Waal, Thomas. 2003. Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press.

Ghaplanyan, Irina. 2010. ‘Empowering and Engaging Civil Society in Conflict Resolution: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh’. International Negotiation 15 (1): 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1163/157180610X488191.

Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. On Populist Reason. London ; New York: Verso.

Militz, Elisabeth, and Carolin Schurr. 2016. ‘Affective Nationalism: Banalities of Belonging in Azerbaijan’. Political Geography 54 (September): 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.11.002.

Tahirzadə, Ədalət. 2021. Meydan: 4 Il 4 Ay: Azərbaycan Xalq Hərəkatı Haqqında Gündəlik-Qeydlər. Edited by Cəmil Həsənli. Qanun.

YouTube, dir. 2013. Baba Punhan – Qarabag Getse Eger. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nlDmOLvMZjg.

———, dir. 2019. Xəlil Rza Ulutürk – Qarabağ. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=giOCMRwjczg.

———, dir. 2020a. Aşıq Yediyar – ” Nə Vaxta Qaldı? “ – Qulp. https://youtu.be/i1txwLvCikM.

———, dir. 2020b. Dağlıq Qarabağ Haqqında Bilmədikləriniz (Heydər Əliyev). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TsSEvha0TTM.

———, dir. 2020c. Əbülfəz Elçibəy – Meydanda. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QtDasuDsnbQ.

———, dir. 2020d. Sabir Rüstəmxanlı, Bəxtiyar Vahabzadə – Meydanda. https://youtu.be/enRjkPuODLM.

———, dir. 2020e. Լևոն Տեր-Պետրոսյանի Ելույթը, 06.11.1988. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BajHInvsA8o.

———, dir. 2021. Qarabağ Tarixi Azərbaycan Torpağıdır! – Sabir Rüstəmxanlı Meydanda. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJSmoUkHGaA.

*The image to the left on the cover image is taken from RFERL. The image to the right on the cover image is taken from EVN Report.