The impacts of unresolved conflict and the layers of isolation they have created are reflected in the everyday lives of the young generation living near conflict-divide. The most enduring problem for school children residing in the Gal/i district is the lack of opportunities to access education in their native Georgian language. Other significant problems residents of Gal/i face today are connected to difficulties obtaining Abkhazian documents, insecurity, mistrust of local law enforcement officers, restriction of movement, ethnic line discrimination, and restrictions regarding studying in the Georgian language.

Learning in a language you don’t understand

The predominantly Georgian population residing in Abkhazia’s Gal/i district still faces a number of problems decades after the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict. Thousands of Georgians fled during the 1992-93 war, yet most Mingrelians [a subgroup of ethnic Georgians] returned to Gal/i when the war ended. Some Mingrelians, especially older people, never left.

Today many residents question if returning was a mistake due to the multitude of problems they face. Problems that make them feel unwelcome and powerless in their own land.

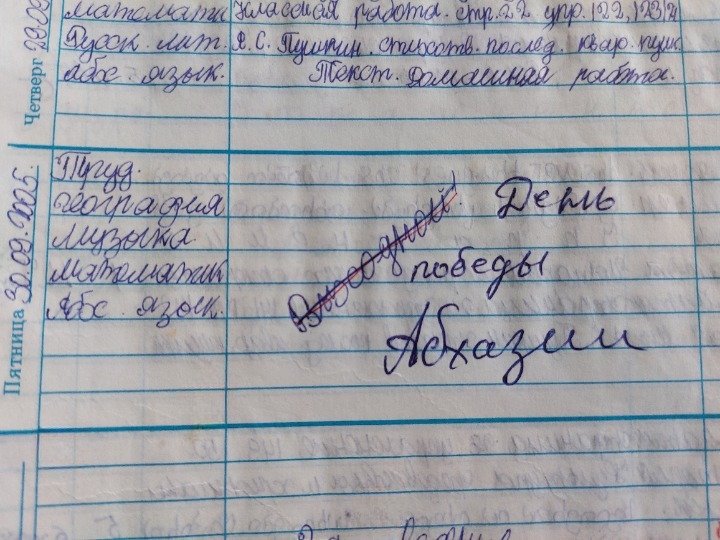

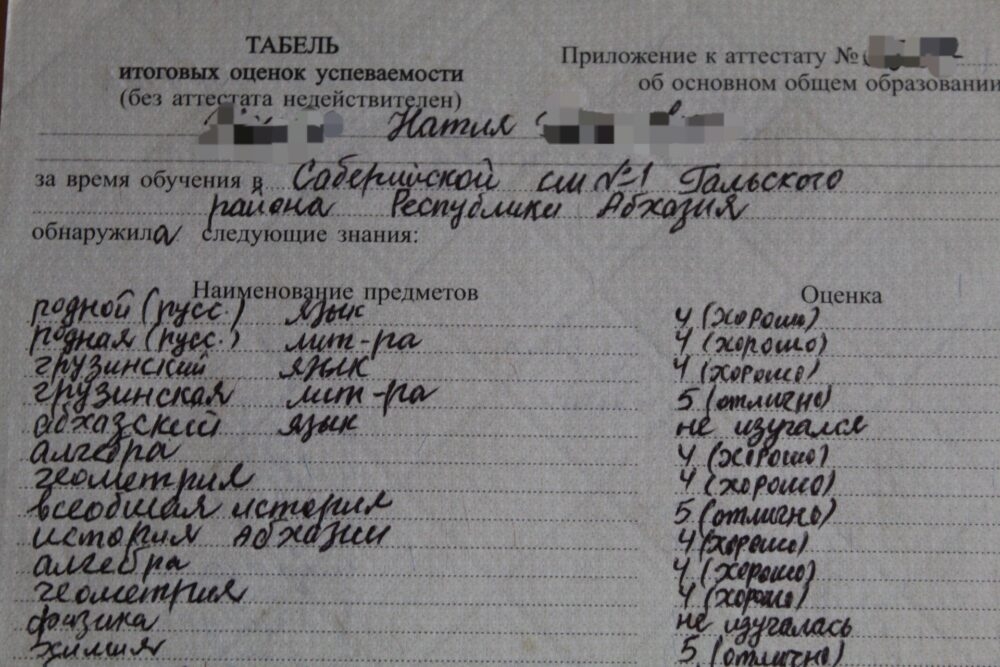

The main challenge faced by ethnic Georgian students in the Gal/i district is the restrictions preventing study in their native Georgian language. All subjects are taught in Russian. In the school diaries and diplomas, it is written that their native language is Russian, a language that is alien to the locals.

While the Abkhaz constitution guarantees every ethnic group in Abkhazia the right to freely use their mother tongue, in practice access to Georgian-language education for ethnic Georgians is restricted.

During the Soviet era the language of instruction in schools was Georgian, which began to be replaced with Russian after the Georgian-Abkhaz war. Today, the Georgian language is only taught as a foreign language in schools for two hours per week. Pupils in one of the upper districts of Gal/i say that their school principal forbids them to speak in Georgian, even when they are outside of the classroom.

Nino (not her real name), 19, graduated from Saberio’s secondary school in 2020. She recalls difficulties and challenges in her school related to the inability to learn in Georgian.

“When we had a Georgian lesson, the teacher was trying to give us as much information as possible, but it was not successful as Georgian language teaching time was limited. We had Georgian class for only two hours in a week. It was difficult for us to study in Russian, especially math was hard for me” – recalls Nino, who managed to pass Georgia’s Unified National Exams.

Giorgi is a graduating-class student from the lower zone of the Gal/i District. He says that because of the chaotic and antiquated curriculum, they find it difficult to compete with their Georgian peers in the National exams.

“There is also a serious problem with the internet in the district, so we cannot fill the gap at least with the internet. Quality of English teaching is also not high, so this prevents us in the future from making a success” – Giorgi said.

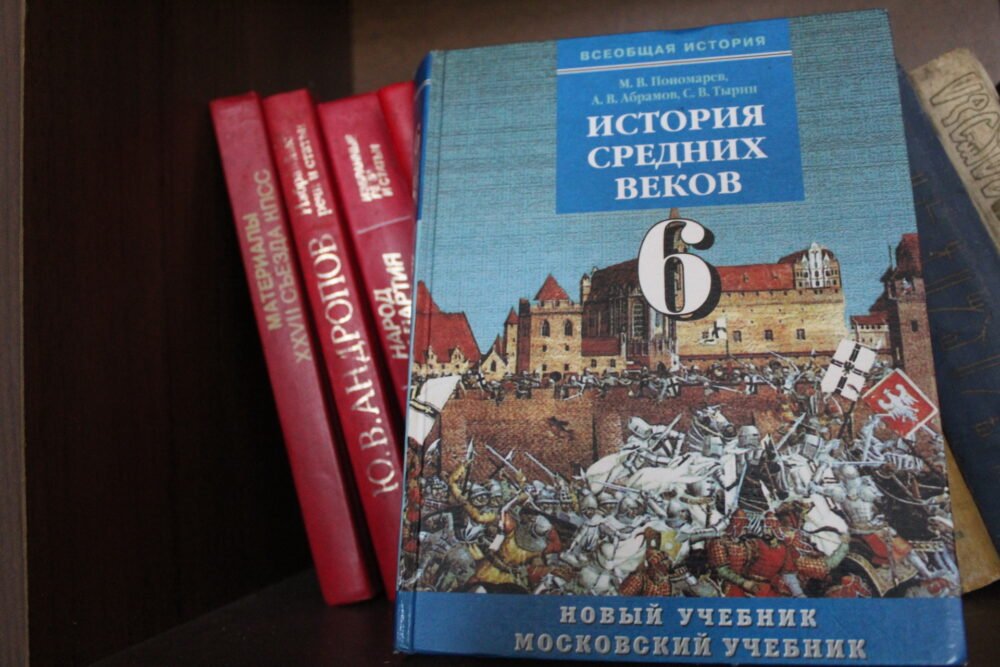

The Russian language is alien not only for the majority of children but also for many teachers and parents. The transition has been especially difficult for teachers, many of whom do not speak Russian fluently. Students are unable to speak and understand either conversational or academic Russian language, and as the parents are not fluent in Russian, they are unable to assist their children or be involved in their children’s school life. Moreover, it is mandatory for pupils to study with books issued in Moscow, and they are obligated to study with the same curriculum used in other Abkhazian school districts.

Maia (not her real name), 64, is a teacher in one of the schools of Gal/i district. In the Soviet period, she graduated in the Georgian sector and says that it is hard for her to conduct lessons in the Russian language.

“I am seeing everyday how much trouble my pupils are having and how difficult it is to learn in Russian. In districts are schools where Russian is taught well and pupils from such schools are good at Russian and other subjects too, more or less, but in some schools, it is not the case and children graduate without good knowledge of Russian and Georgian”, — she says.

According to teachers and parents from the Gal/i district, children find it difficult to study in Russian and are not motivated to learn as they have difficulty understanding the texts. In the Gal/i district instruction in the Georgian language is prohibited in all pre-school education institutions and parents are forced to send their children to Russian-language kindergartens.

Nona (not her real name), 48, a mother of three, says it was difficult for teachers to conduct lessons in Russian. She struggled to explain study materials herself as the content of lessons was not understandable for pupils.

“Gali district’s teachers are mostly Georgian institute graduates in Soviet times. That is why it is hard for them to teach for example biology, chemistry, or physics in Russian. I was trying to help my children with Georgian and other humanitarian subjects, but I could not explain physics or chemistry of course”.

Due to this difficult situation, parents who live near the conflict divide prefer to send their children to school in the neighboring Georgian-controlled region of Samegrelo. A number of students were crossing the dividing line, yet because of the COVID-19 pandemic, crossing points were closed. As children were unable to travel through these crossing points, they missed their classes.

Prior to the pandemic and the closure of the dividing line, access to education in the Zugdidi municipality was considerably restricted over the past several years because of the changes and complications involved with moving across the checkpoints.

While schools switched to online teaching due to the pandemic, most students in the Gali district found themselves behind in the lesson process. Access to the internet is a problem in the district, which is why most of the children have not taken lessons in any form during almost one school year.

“Last year [2020] we only attended September in school. I was so sorry for the children, not many have access to the Internet. Only 3-4 students from the whole class were able to attend the online lesson” — told one of the teachers from the Gal/i district.

Natia (not her real name), 17, is a graduating student. She says that since September 2020 through March 2021, lessons have not been conducted either in traditional or remote format because, like others in her class, she does not have the internet access necessary to attend online lessons.

“Since the school closed, my class and I have not had a single lesson since. I do not have internet, I have a 20-tetri package of Bali [Georgian Mobile network provider], but connection was very low and it was impossible to attend an online lesson via zoom” – said the 11th grader.

According to the State Ministry for Reconciliation and Civic Equality of Georgia, prior to the 1990s conflict 58 schools were operating in Gal/i district, out of which 52 schools conducted instruction in the population’s native language, Georgian. Following the conflict, the number of schools was reduced to 31, one school additionally closed in 2017. Today there are 19 schools in Gal/i district.

From 1994 to 2015, Russian gradually replaced the Georgian language in all schools. In 2015, in 11 schools within the lower zone of Gal/i where education in Georgian was still maintained, instruction in the initial four grades shifted to Russian. In 2016 and 2017, 5th and 6th graders, respectively, also shifted to instruction in Russian.

In September 2021 education in Georgian, including 11th grade, was completely banned in the whole Gal/i District.

Freedom of Movement

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, movement on the Engur/i Bridge was restricted for more than a year, and locals have not been able to move freely in Georgian-controlled territory. The border with the Russian Federation was also closed, but while Sukhum/i opened the road to Russia in October 2020, restrictions on the Engur/i Bridge remain till 5 July 2021. Before the pandemic, the dividing line was closed two times in one year for an undetermined period. According to the European Union Monitoring Mission (EUMM) survey, 2,580 people cross Engur/i Bridge every day when it is open. This meant that for more than a year, essentially this same number of people faced difficulties every day.

Locals prefer to buy food and medicine in Zugdidi, a city bordering Gal/i, as prices in Gal/i are significantly higher. Many seek medical care in Georgian hospitals as there is reportedly a lack of both medical equipment and qualified doctors in Gal/i hospitals, which locals complain are in dreadful condition. Many go to funerals, and weddings, for business, to study, to receive pensions, to visit relatives, and for many other reasons. When movement is restricted, locals have no choice but to cross the conflict divide clandestinely. According to Apsnypress, based in Sukhum/i, around 3, 000 residents of the Gal/i district were detained during three months – from January 1st to April 1st in 2021- for “illegally” crossing the dividing line.

Locals say they face a number of issues due to restrictions preventing them from obtaining Abkhazian documents and their lack of Abkhazian passports. The obligation to possess Abkhazian documents has been mandatory since 2008 when Russia recognized Abkhazia’s independence. Before this time, residents of Gal/i were mainly using Soviet passports and birth certificates for minors. Since 2008, ethnic Georgians are obliged to obtain an Abkhazian residence card, a document explicitly meant for foreign citizens.

The residence permit places restrictions on their rights, for example, to buy a new house and other property, or even to vote. In order to receive an Abkhaz passport, Sukhum/i requires ethnic Georgians to renounce their Georgian citizenship or change their names and register themselves as ethnic Abkhaz or Mingrelian.