In 2024 alone, deportations of foreign nationals more than doubled, and those who dared to protest increasingly found themselves targeted. From Tbilisi’s swelling demonstrations to border denials and unexplained removals, the shift is clear: Georgia’s pro-European dream is colliding with an authoritarian turn—one that is not only changing policy but also uprooting lives.

2024 Was a Turning Point for Georgia: The adoption of the infamous "foreign agent law," the attempt to impeach Georgian President Salome Zourabichvili, the approval of homophobic laws, contested elections, and further the ruling party distanced Georgia from the European Union while thousands of citizens flooded the streets of Tbilisi, demanding a future anchored in democracy and Europe.

But beyond the headlines, this shift is tangibly changing people’s lives: Some describe the heavy air in Tbilisi as fear, others as insecurity and, some as anger. However, the shift in Georgia’s political vector, what many call a transition toward an "authoritarian" regime, is not just about emotions. It’s about a tangible change in the quality of life.

This shift affects not only Georgian citizens but also foreigners living in Georgia who don’t hold Georgian citizenship. But how?

Deportations, Deportations, Deportations and the Thought of Leaving/ or /“Then why did I leave Russia?”

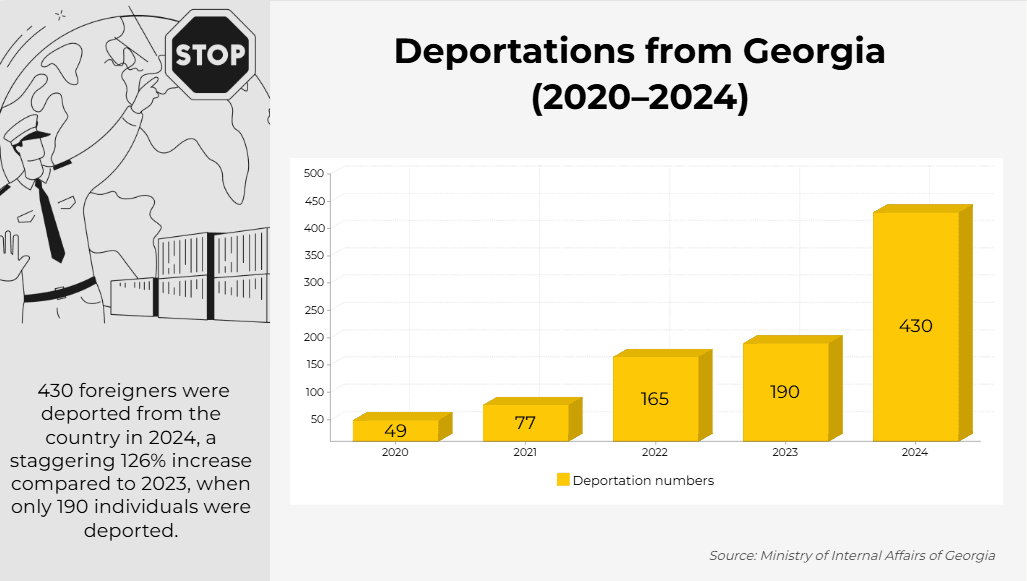

According to data published by Georgia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA), 430 foreign nationals were deported from Georgia in 2024, an increase of 126% compared to 2023, which saw 190 deportations. The trend is not new, but the pace is accelerating.The numbers show a consistent upward movement, but 2024 marks a significant leap. The first three months of 2025 alone saw 219 deportations, surpassing the entire year of 2020 and rival the total for 2022.

Despite these figures, activist and journalist Anya August, who moved to Georgia from Russia after the invasion of Ukraine, didn’t initially fear facing deportation.

“The vibe then was that Georgia and Russia were, you know, in conflict. And I think I didn’t know a lot about Georgian politics. But I didn’t see any of this coming. And when they got this ‘foreign agent’ law, I thought: okay, I guess I will have to move to some other foreign country at some point. Because when it starts, you just know what will follow and follow and follow.”

Anya, a coordinator of the Feminist Anti-War Resistance and a journalist at a media outlet “LGBT propaganda” , moved to Georgia with her girlfriend. After the war began, she waited a few months in Russia, gathered funds, and immigrated. When Georgia’s parliament passed the homophobic “On Protection of Family Values and Minors” law in June 2024, Anya realized she could no longer be a drag queen in Georgia, and they decided to move to Spain.

“My girlfriend decided, okay, let's move to Spain because LGBTQI+ got banned at this point. We gathered everything. We dropped our flat and so on. We packed up, and my girlfriend left. I went to Armenia to wait for the visa, and I never got it.”

Over time, the queer community from Russia has grown in Georgia. They created Kvira Queer-space, a safe zone where members can express themselves freely and organize events. But despite these efforts, the queer community continues to emigrate, and those who remain, as Anya says, are the most undefended category.

“They stay because they don't have money to move anywhere else. I deeply care about them. You know, you run from one homophobic place just into another homophobic place, and you're... locked into the cycle. And also this place [Kvira Queer-space] where we sit, it wouldn’t be working at all if one of our founders didn’t have a real job to pay the rent.”

Anya doesn’t want to leave. She wants to be where she’s needed—where her community is.

“I feel like I belong here. But it looks very sad. If this place closes, it will just be... sad.” Anya says ideally she would have liked to stay longer in Georgia. But she says if she can’t be outspoken about this, then why did she move out from Russia in the first place?

Border Rejections without Explanation

Georgia, once considered a “safe space” for foreign journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens, is rapidly losing that status. This is what Arsen Kharatyan believes. Kharatyan, the founder of the Armenian-language outlet Aliq Media in Georgia, was denied entry into the country twice in September 2024. Despite having lived in Georgia, he says no explanation was given for the refusal.

“My understanding is, it probably has to do with several factors. One is the fact that our organization, Alik Media, has not registered as a foreign agent in the country. The second could be related to some civil society organizations that we have very close ties with, and we’ve been helping some of them find or register in other places outside of Georgia. But I don’t have any clear, specific understanding of why this happened.”

Kharatyan’s case isn’t isolated. In 2023, journalist and writer Viktor Shenderovich was denied entry. A year later, Russian activist Maks Ivantsov was also barred from returning to Georgia. Similar incidents occurred with Czech and Belarusian journalists, and in 2025, Regina Jegorova-Askerova, a Lithuanian human rights defender who had lived in Georgia for 15 years, was denied entry.

As Kharatyan notes, “Democracy in Georgia is degrading. And we see other laws and regulations coming. In the near future, we should probably expect more repressive approaches to civil society and free speech in general.”

The laws being passed in Georgia’s parliament and the protests in Tbilisi demanding a pro-European future affect not just one country, but the region as a whole.

“Besides the issue with the journalists, it’s also a problem when you have a neighboring country that has a European, pro-Western course, and the government takes actions that do not necessarily match those European or Western values. So, of course, we’re quite concerned it could have a larger impact on the region.”

Is Georgia No Longer a Safe Space?

According to the MIA, some of those deported were involved in “anti-social behavior” or “violations of administrative law.”

In January 2025, the Ministry reported that 91 foreign nationals had been deported in November and December. Of those, 25 had participated in protests in Georgia.

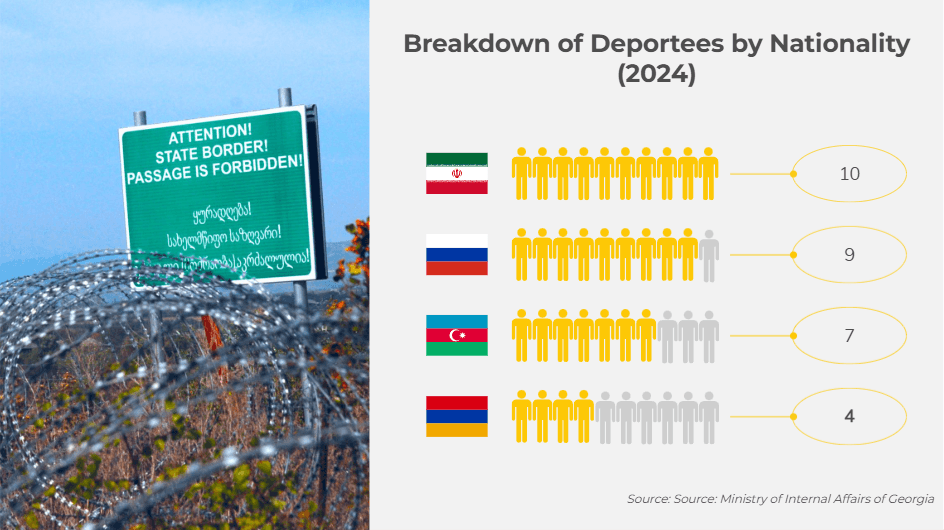

One could argue that the deportation policy is increasingly being used as a political tool, especially against those connected to protest movements or critical journalism.Since April 2024, Georgia’s MIA has been publishing monthly reports about deportation figures and countries of origin. Though the reports don’t provide a precise breakdown, they do mention nationalities: Armenia is listed 3 times, Azerbaijan 7, Russia 9, and Iran 10 across 11 months of data.

According to JAMnews, in 2023, 41 Azerbaijanis were deported from Georgia, making them the majority among all deported foreign nationals that year.

For years, Georgia was a safe space for Azerbaijani journalists and activists facing repression at home. That changed in 2017, when investigative journalist Afghan Mukhtarli disappeared from Tbilisi, only to reappear the next day in an Azerbaijani prison. His abduction sent shockwaves through the regional civil society.

Uzeyir (name changed), an Azerbaijani journalist based in Georgia, says they no longer feel fully safe:

“In the past, journalist Afgan Mukhtarli was abducted in Georgia, so none of us have any illusions. It is just safer here than in Azerbaijan. Now, the authorities have detained Afgan Sadigov and are trying to deport him. The European Court of Human Rights has prohibited this, but the incident is still a clear signal.”

Uzeyir says the recent political events in Georgia haven’t directly affected him, but there have been several cases of journalists and activists being denied re-entry after traveling abroad.

“And overall, it is painful to watch a country that was almost free not so long ago now rushing headlong into authoritarianism. Everyone who came here from authoritarian and totalitarian states recognizes the signs of what we all eventually fled from.”

Although Uzeyir says he loves this country and doesn’t want to leave, he has also never seen Georgia as a final destination. He is now considering moving to Europe—because “returning home is not an option.”

Georgia at a Crossroads

The streets of Tbilisi continue to echo with voices demanding a European future, while the policies of those in power steer the country in another direction. The space once seen as a regional sanctuary is shrinking. For many foreign citizens, especially activists, queer individuals, and journalists, Georgia is no longer a heaven, but a place of uncertainty. And yet, their presence and resistance still carry weight, reminding us that the struggle for freedom transcends borders.