“Our borders were not of our own drawing. They were drawn in the distant colonial metropoles … with no regard for the ancient nations that they cleaved apart. At independence, had we chosen to pursue states on the basis of ethnic, racial or religious homogeneity, we would still be waging bloody wars these many decades later. Instead, we agreed that we would settle for the borders that we inherited … Rather than form nations that looked ever backward into history with a dangerous nostalgia, we chose to look forward to a greatness none of our many nations and peoples had ever known.”

Mbugua Martin Kimani, Kenya’s UN Ambassador (2022)

Introduction

The contemporary understanding of state borders can be dated back to the emergence of the territorial state and state system based on territoriality in place of dynasties. Having become increasingly common with the Peace of Augsburg and the Peace of Westphalia (Diener & Hagen 2012, 40-41), maps have not only shown what is where but also accentuated the limits of the territory under one’s rule.

In spite of their function in the formation of nations, borders had long been taken for granted in social sciences, particularly prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, as the boundaries dividing nations were regarded merely as administrative instruments in stasis. Yet, the roles of borders were not completely unnoticed. For instance, as far back as 1983, Anderson mentioned “the map” as one of the three primary institutions employed for nation-building along with “the census” and “the museum” (2006, 163). However, it was not until the early 1990s that borders became a focus of academic interest on a larger scale due to two simultaneous yet contradictory trends. Along with the end of the Cold War, new states and borders appeared on the world map. In addition to their administrative functions, borders began to be acknowledged as a dividing line between the Self and the Other, and therefore a constitutive of collective identities. At the same time, the culminating exchange of goods, money, information, and people across the world intensified interdependence and globalization, which in turn triggered a discussion on the disappearance of borders (Newman, 2001).

However, the end of history (Fukuyama 1989) thesis that envisaged the peaceful coexistence of democratically ruled world nations that would make borders obsolete failed to come true. 20 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, border security occupied the pages of newspapers and inspired academic publications responding to the migration crisis that forced millions of people to flee their countries due to the so-called Arab Spring and other conflicts in the MENA region. Since the early 2010s, the EU has been struggling to devise an adequate border policy to ensure security without ignoring its core values prioritizing human rights, equality, and non-discrimination. The crisis on the borders of the union has not only been influential in deepening the internal divisions between the members (Crawley 2016) but has also intensified the criticism against the EU, including from those accusing the union of being an empire and exploiting its own values to stop asylum seekers from crossing its borders (Greenhill 2016).

Besides the dividing and identity-forming functions of borders, they are also bridges that connect groups of people, enable the exchange of goods, and consequently produce cooperation (Prescott & Triggs 2008, 5-6). The smooth flow of people and goods across different countries requires safety, as several circumstances can disrupt it. These include smuggling, illegal border crossing, natural disasters, epidemics, and cross-border violence (Diener & Hagen 2012, 66). People living near a borderline suffer in particular when the two sides start a military conflict. In a matter of days, if not hours, citizens of one country might find themselves within the de facto boundaries of another due to territorial takeover.

This is exactly what Azerbaijanis experienced in the early 1990s and Armenians in 2020. When the first and second wars broke out between Armenia and Azerbaijan, nobody asked the people living near the border of the two countries, or within the disputed territory, whether they wanted to stay in the country they had previously resided in. Thousands of people who had ordinary lives became forced migrants. Others continued their lives under the threat of being shot by the military forces of the other side (Reuters 2017; Avetisyan 2021).

Considering the failure of the idea of a borderless world and the risks faced by communities living on borderlands without a peace agreement and mutual recognition of the boundaries, we argue that any discussion of the abolition of borders between two states previously at war is nothing but utopic. Instead, a proper process of delimitation and demarcation is likely to contribute to peacebuilding. However, these processes cannot alone be expected to build peace. Rather, they should be seen as a phase or an initial stage toward building peace. This paper is concerned with the question of why the completion of delimitation and demarcation of the Armenia-Azerbaijan boundary is significant for peace and how it should be conducted.

Azerbaijan’s Position on Delimitation and Demarcation

Armenia’s proposal on delimitation and demarcation delivered to Azerbaijan via Russia included the mirror-way withdrawal of the two sides’ armed units (JAMNews 2022). The Azerbaijani side, however, asserted that there should be no preconditions for the delimitation and demarcation of the border in order to complete the process as soon as possible (APA 2022). In short, Azerbaijan’s official position is that the delimitation and demarcation of the border is a precondition for the normalization of relations and a conclusive peace agreement between the parties. This was restated in “Azerbaijan’s proposal on the basic principles for the establishment of relations between the two countries” (AzerTac 2022). It is clear that, as the victor of the latest war, Azerbaijan refuses to give up direct control over the territories regained with the November 10 ceasefire statement and seeks to complete the demarcation of the boundary unilaterally in the absence of a delimitation agreement. Also, Azerbaijan’s assertive stance on demarcation appears to be a tool to force Armenia to come to terms with the former.

It can be argued that Azerbaijan’s assertive policy has reached this goal. That is, the two sides announced the creation of respective delimitation commissions and their first meeting soon after the trilateral meeting among Aliyev, Pashinyan, and European Council President Michel on May 22, 2022.[1]

The heads of both commissions are the deputy prime ministers of Armenia and Azerbaijan, Mher Grigoryan and Shahin Mustafayev. The Armenian commission includes 11 other members: the ministers of Foreign Affairs, Defense, Justice and Territorial Administration; the deputy chairman of the Cadastre Committee; the commander of the Border Troops of the National Security Service; and the deputy chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces. Meanwhile, the Azerbaijani commission consists of representatives of 22 ministries, including the deputy prime minister of Nakhichevan; six deputy ministers; the first deputy head of the State Security Service; the deputy head of the State Border Guard Service; the deputy head of the Foreign Intelligence Service; as well as the mayors of Dashkesan, Kelbajar, Lachin, Ghubatlu, and Zangilan regions.[2] The first inter-commission meeting was held on 24 May and the parties agreed to meet next in Moscow and Brussels.[3]

Armenia’s Position on Delimitation and Demarcation

The November 10 ceasefire put an end to the 44-Day War between Armenia and Azerbaijan but created a huge wave of dissatisfaction within Armenian society. While Azerbaijan started marking the boundary unilaterally, the Armenian population saw this as direct aggression against the territory of the Republic of Armenia. The cause for this frustration was the fact that, unlike the 44-day war which was taking place in the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh and the internationally recognized territory of Azerbaijan, now the Azerbaijani soldiers were crossing the official border of the Republic of Armenia. Armenian society assumed that Russia would prevent such escalations based on the Armenian-Russian strategic alliance, including the agreement on military cooperation and Armenia’s membership in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Officially, Yerevan applied separately to both the CSTO and the Russian Federation on the matter, yet they refused to take action. This refusal further increased the fear of the Armenian population.[4]

According to the news channel Factor.am, Azerbaijani forces crossed the border in the regions of Sev Lake/Qaragöl and Gegharkunik, near the village Verin Shorja. The channel was citing the Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Armenia (Arman Tatoyan) started addressing the border crisis since it began, visited border regions where the Azerbaijani troops advanced to examine the impact on the advancement of human rights and security. Responding to his inquiry, the Armenian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) clarified on December 29 that demarcation is a bilateral process that requires a joint commission to come to a bilateral agreement, only after which demarcation can be carried out. The statement continued:

“Prior to the above-mentioned process, the deployment of armed forces or border troops to conduct combat duty along the state border is a purely defensive security measure … negotiated directly or indirectly between representatives of the armed forces… that cannot be interpreted as a final agreement on demarcation, or mechanical approval of existing administrative boundaries.”[5]

It is essential to state here that our issue is not to prove or disprove these transgressions, nor do we try to justify one side and blame the other. These examples are given here to once again highlight the importance of not only high-level state officials but also regular soldiers and especially the border population being aware of how the processes of delimitation and demarcation function.

As mentioned above, Azerbaijan’s official position is that the process of delimitation and demarcation is the only precondition for the normalization of relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and the final peace agreement. The situation in Armenia is more complicated due to the stance of officials within Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. Moreover, the Artsakh government declared martial law and its parliament came out with a statement that forces the Armenian government to step back from Armenia-Azerbaijan peace negotiations and any process of delimitation under circumstances that do not ensure Artsakh entirety and independence (https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31803753.html).

After the November 10 treaty, some of Armenians within the Republic of Armenia as well as the diaspora accused Pashinyan of surrendering lands and treason. On various occasions both within Armenia and outside, Armenians protested against Pashinyan with banners calling him a “traitor.”[6] However, even with such a wave of disagreement with his actions and hate directed toward him, Pashinyan was reelected as prime minister in the June 20, 2021 parliamentary elections. What began as general frustration in the public and a shock wave against losing the Second Nagorno-Karabakh war was picked up by the current opposition led by Robert Kocharyan and allies. The accusations against Pashinyan and the current Armenian government led by the opposition consist mainly of representatives of the former government and continue today, backfiring on the process of accepting the demarcation process.[7]

The clash between the supporters of and opposition to Pashinyan’s government increased after his last speech at the National Assembly on April 13, 2022. In his speech, Pashinyan expressed distrust toward Baku, adding that he sees a possibility that Azerbaijan would bring the talks to a deadlock and take the opportunity for new aggressions against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. He raised the same concerns regarding the process of delimitation, as well. However, he concluded that standing still and not making any progress is an equally great if not greater danger (Pashinyan’s speech at the National Assembly, 13.04.2022).

This means that Pashinyan is accepting international norms for the processes of delimitation and demarcation based on the de jure facts relevant to the clarification of the boundaries of the Republic of Armenia and not based on rumors, wishes, or biblical tales. He restated this also during his interview with Al Jazeera TV.[8] The Brussels agreement on delimitation was based on the agreements reached in Sochi on November 26, 2021. Finally, Pashinyan stated that Armenia never had territorial claims from Azerbaijan and that the Karabakh issue is not a matter of territory but of rights. Therefore, the security guarantees of the Armenians of Karabakh, the provision of their rights and freedoms, and the clarification of the final status of Nagorno-Karabakh are of fundamental importance for Armenia.

Based on Pashinyan’s speech and interviews we can see at least at face value Armenia’s official stance on the process of delimitation and demarcation. We should also note here that for the first time Armenian authorities gave their population insight into how the process of delimitation and consequently demarcation should work. However, unlike Azerbaijan, which posted a list with the names of every member of the commission, the Armenian side only announced the name of the head of the commission. No official list was available on government websites at the time of writing (www.e-gov.am; www.mfa.am).

Before trying to analyze whether the process of delimitation and demarcation will fuel more conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan or result in a final peace between these two countries, below we present how these processes of delimitation and demarcation should take place in theory based on a summary of relevant literature.

The Process of Delimitation

In the ever-changing course of humankind’s history, there have been no empires or polities that lasted forever. Hence, the formation of new states on the world political map is common and currently more visible given recent events in Ukraine. The Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of the States signed in 1933 at the 7th Pan-American Conference (OSCE 2017, 10) is one of the few international instruments that characterize the legal personality of a new state from the standpoint of international public law. The convention established four main characteristics of a state as a subject of international law: a) permanent indigenous population, b) defined territory, c) native government, d) capacity to start civilized relations with other states.

A newly formed state does not emerge out of nowhere on a no-man’s land. It generally occupies the same territories it used to but with a different legal status. One of the fundamental tasks for newly formed states is to establish their boundaries. Oftentimes such states jump into self-defense without having yet settled their boundaries. This naturally causes conflicts with neighboring states at different levels due to uncertainty about the limits of the territory to be defended. Such is the example of Armenia and Azerbaijan after the establishment of their first republics prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Referring to the existing literature, Prescott and Triggs illustrate a distinction among the concepts of frontier, border, and boundary. The former refers to the vast, uncontrolled soil dividing two political entities. These kinds of territories are now extinct as the world has been divided between states and they execute a degree of control over almost the whole terrain. Border, on the other hand, denotes a narrower strip of land along the boundary—that is, the line dividing the territories controlled by different states on two sides (2008, 12).

The process that establishes and ensures the maintenance of boundaries between two states is described as involving four steps, as listed by Prescott and Triggs (2008, 12):

a) Allocation describes the initial political division between two states.

b) Delimitation means the selection of a boundary site and its definition.

c) Demarcation refers to the construction of boundary markers in the landscape.

d) Finally, administration is concerned with the maintenance of those boundary markers for as long as the boundary exists.

Ideally, these four steps are all followed in sequence. However, in practice one or more steps are often ignored or they are executed in a different order.

This paper is particularly concerned with the procedures of delimitation and demarcation, although this does not mean that the other aforementioned steps are of less importance. The delimitation of a boundary is defined by OSCE as the “legal formalization in a treaty of the state boundary between adjoining states” that determines the positions of the sides on a topographic map and their written description. Demarcation, on the other hand, involves the physical marking of the boundary line (OSCE 2017, 8).

To avoid future conflicts over undelimitated boundaries and act in accordance with national legislation, a political decision to start the processes of boundary making must be taken at the initiative of the president or parliament of a country. The government must set up a working group or a commission and instruct it to prepare a report on the legal, political, economic, and technical situation regarding the status quo of the boundary. This group must include a few specialists in the fields of cartography, geology, natural resources, etc. Representatives of a president’s executive personnel, parliament, government, as well as concerned ministries are also to be part of this commission.

The negotiating position is based on two principles: a) from the general to the particular, b) from the ultimate to the optimum. The latter means that negotiations should begin with an ultimate position which later should be reduced to the optimum one until it becomes acceptable for all parties. Some provisions regarding the border or territory are usually recorded in the declaration of independence, constitution, treaties of friendship, good-neighborliness, and in cooperation with adjoining states (OSCE 2017, 14). While developing its position on delimitation, a state refers to a number of sources, including international norms and customary law; international agreements; national constitution and other related laws; topographic and other types of existing maps; natural boundaries such as watersheds, rivers and lakes, artificial objects; and ethnographic division (OSCE 2017).

Delimitation is a long process. For such a process one needs to keep in mind that maps tend to age due to changing situations on the earth’s surface, as well as anthropogenic and natural impacts. Yet, the main working document in the preparatory stage of delimitation and during subsequent negotiations is a topographic map, where the administrative boundaries and state boundaries are drawn up. Maps are widely used when states formulate their positions prior to delimitation negotiations. Yet the probative value of existing maps is a point of contradiction in international law and the practice of delimitation. Prescott and Triggs review several cases including the ICJ and other courts’ decisions on disputes between Burkina Faso and Mali, Eritrea and Yemen, Qatar and Bahrain, and the UK and France, concluding that maps are oftentimes ignored or assigned no value separate from the texts or other evidence accompanying them. Moreover, they mention that international courts have sometimes expressed their concerns regarding the lack of technical capacity at the time to draw accurate maps. Finally, the maps prepared by one of the involved parties are usually discarded as evidence due to biases and deliberate manipulations (2008, 194-202).

Historical documents, especially maps, data on population censuses, and administrative maps may help in tracking the dynamics and trends of changes in boundaries. However, too much history can spoil the talks (Huseynli, Ghazaryan 2022). While dealing with nation states and their boundaries, the parties involved should not go into the depths of history and try to justify their claims with the ‘endemicity’ factor. Thus, a modernist approach, i.e., focusing only on the last hundred years, is a more viable path for negotiations.

At the very onset of states’ emergence, their territories were marked by natural frontiers (mountains, rivers, seas, lakes, swamps, forests, deserts). Over the course of history as more conflicts and wars erupted, borders gradually shifted to natural obstacles which turned into the first defense line, which were easy to defend. Today, the importance of natural boundaries in the practice of delimitation is still evident, as they are cheap to identify and easy to guard. Along with natural boundaries, artificial or man-made ones are also commonly used for delimitation. Such artificial boundaries can be roads and railways, bridges, power lines, pipelines, land reclamations and irrigation facilities, and dams (OSCE 2017, 23). At the preparatory stage of negotiations, it is critical to take into consideration the importance of artificial boundary making objects not only for the home state but also for the neighboring state and especially cross-border populations.

On the other hand, the international legal principle vis-à-vis state boundaries is uti possidetis juris, which entails the preservation of boundaries that have existed prior to the time when the state gained independence (OSCE 2017, 14). That is, the adjoining states are bound to accept each other’s boundaries with previous administrative borders after a new state inherits a territory. Yet, determination of international boundaries is not strictly regulated by universally accepted procedures.

Based on the above-mentioned activities and nuances, the working group submits to higher authorities the proposal for selecting an initial negotiating position, provides models for further actions in boundary establishment, provides a list of problem areas and recommendations for their elimination, and estimates on the consequences of the steps to be taken with regard to political, economic, defense and other interests of the state. This report is then evaluated and amended. Afterward, its final form becomes the negotiating position of the state. Besides the legal and technical aspects, the report should address the concerns of the local population near the boundary, who, after delimitation and final demarcation, may remain abroad. The same applies to the population of remote areas called “enclaves.” Many states face such problems and proclaim their intentions to annex these territories. If the relevant territories are ethnically homogenous, both countries have to stipulate terms of exchange and the problem will be solved. In practice, there are no such ‘pure territories’ in ethnic and/or religious terms. This has naturally caused and still causes conflicts on different levels and the solution to this problem remains to be found. Hence, it is recommended that the issues of setting a boundary and the problems of border/enclave populations not related to the technical and legal subtleties of delimitation should be divided and resolved separately under different commissions (OSCE 2017, 24).

Once the negotiating position is approved, the government of the country creates a delegation to work in a joint commission and appoints a leader. This process is similar to the appointment of the working group. There is a specific language of diplomacy and status asymmetry applied in the meetings of the commissions from the states negotiating over the delimitation of boundaries. The party initiating negotiations informs the neighboring state by filing a note expressing a desire to proceed with negotiations and proposes consultations on the approval of the regulations for a joint commission. After preliminary agreement on regulations, the governments approve their national version with a note that the commission should have the right to make amendments that do not change the essence of the regulations (OSCE 2017, 25).

Negotiations on establishing boundaries are a sensitive topic not only because of the attention of the press and politicians but also because the public at large and especially border populations also follow developments. Every cheerful exclamation from one side may create animosity in the other. Any premature, uncoordinated, or unverified information about future decisions on the boundary may trigger unnecessary unrest and suspend or interrupt negotiations. Hence, people’s diplomacy is not always constructive (OSCE, 28). This, however, does not mean that people and especially border populations should not be aware of the basic definitions of delimitation and demarcation and how these processes work. The process of negotiations has 12 OSCE-approved/suggested commandments. Due to the limitations of this article, we will not present all of them here. However, we must note one that is related to Armenia’s and Azerbaijan’s negotiations before the Second Nagorno-Karabakh war. This commandment states that the sides should not resort to ultimatums or extreme slogans, such as ‘not an inch of ground’ (OSCE 2017, 29) or “Nagorno-Karabakh is Armenia,” the latter an announcement that Armenian Prime Minister Pashinyan made in Stepanakert weeks after the Velvet Revolution.[9]

The commission should use only homogeneous maps that have a common cartographic framework, from approximately the same date of issue or update, as well as the same accuracy characteristics. Delegations make a thorough comparison of the line’s position on the maps, analyze legal documents underpinning these positions, and identify problematic areas. In order to identify differences that might arise, the parties can organize field visits to the sites for more detailed analyses of the issue. The commission should also discuss the possibility of and principles for applying optimization procedure to the state boundary. After the state boundary line has been optimized along the whole perimeter of the boundary, a table of compensated areas should be compiled (OSCE 2017, 38). The main element of a delimitation map is the state boundary, which, if possible, should pass within the central part of the map and be displayed with a corresponding red symbol. The agreed-upon line should be moved from working maps to updated ones that will be used to generate a final delimitation map.

Due to secrecy restrictions imposed on maps in some countries, delimitation maps usually display a border belt of a limited width of one or two kilometers on either side of the boundary, depending on the scale of the map. In international and national practices, a system of map division is used where maps are divided into separate sheets. For this purpose, a non-standard map division for delimitation maps is used that is developed by a specialized cartography working group. These delimitation maps are then bound together in an album where the sheets are numbered, tied together, and sealed by both parties. The sealed album of the delimitated map then becomes the main document of the International Treaty on the State Boundary (OSCE 2017, 40-46).

On average, negotiations on establishing boundaries last a minimum of 10 years, during which the maps used should be updated at least once. In fact, the maps used on the date the treaty is signed can be roughly 15 years old. The ratification of the treaty can take another two years and the final creation of the Joint Demarcation Commission and the start of its real work can take another five years. In general, with the most optimistic calculations, the joint processes of delimitation and demarcation can last 20 years. (OSCE 2017, 46).

To solve problems that might occur during the boundary-making process a package of treaties and agreements is used. They are signed together with the boundary treaty and include agreements on state border regime; simplified border crossing procedures for the cross-border population; checkpoints for local traffic; and joint use of transboundary water, roads, pastures, etc. Such package agreements can help resolve most of the problems that may arise and significantly speed up the overall process (OSCE 2017, 49).

In the absence of any opportunity for the successful completion of negotiations on establishing boundaries along the entire perimeter, it is recommended that the uncoordinated section/s should be “excised” from the treaty and a “grey area” formed along its outline. This area should be attributed to a special regime provided by the parties, which will be in effect until the position of a delimiting line is agreed upon and legally formalized.

The process of delimitation and demarcation can be mediated by a third party if both contracting powers agree on this. There are several types of mediation that can be used by a third party:

a) traditional mediation, where the final decision on the point of substance is taken by the negotiating parties;

b) consultative mediation, where a mediator can articulate its position on the issue in question through consultation; this opinion is not binding for the parties but should be taken into consideration;

c) mediation with arbitration elements, where in case of a deadlock in negotiations, the mediator comes up with a binding decision on the issue in question (OSCE 2017, 50-1).

The Process of Demarcation

The term “State Border Demarcation” stands for the explicit marking of a state boundary course along its entirety on the ground based on the developed demarcation documents. This is a complex process and the next stage after delimitation. However, demarcation is not just a technical execution of delimitation. It also implies the activities of state bodies and national delegations in the domain of foreign policy and international law. Demarcation work results in a well-defined, harmonized state boundary demarcated on the terrain in accordance with a treaty on state boundary and demarcation documents that fix the position of the state boundary on the landscape and confirm the consent of adjoining states to its position. The main goal of demarcating state boundaries is to provide the unambiguous identification of a state boundary course on the ground via visible boundary markers and the undisputed documentation of the state boundary on the ground in case boundary markers get lost.

Demarcation also allows for the creation of appropriate conditions to maintain law and order within the state border, giving rise to the cross-border population’s awareness of the presence and importance of state boundary, increasing the effectiveness of counteraction against illegal cross-border activities, preventing border incidents and conflicts between local populations and state services, and strengthening state border protection in accordance with recognized standards of integrated border management (OSCE 2017, 59).

The boundary demarcation process falls into six stages:

a) creating a system for ensuring a state’s activity in the state boundary demarcation;

b) selecting a model for marking the position of the boundary on the ground and developing the documents that regulate its implementation;

c) transferring the delimitated line in-situ and demarcating it with boundary markers;

d) performing cartographic, geodetic, and other works for final draft documents of demarcation;

e) preparing draft summary documents of boundary demarcation and accepting the demarcated boundary;

f) preparing summary demarcation documents and conducting domestic procedures necessary for their coming into force (OSCE 2017, 60).

With a view to the legal regulation of demarcation works, adjoining states usually conclude an international treaty that determines the procedure for a joint commission on boundary demarcation and basic organizational issues. The organization of demarcation works largely depends on the length of the boundary to be demarcated, the geographical and physical conditions of the terrain, as well as the level of mutual relationships between the adjoining states. There are no regulations regarding the number of members to be included in the delegation for demarcation. The adjoining states should be guided by the principle of reasonable sufficiency when it comes to the number of the delegation members, having also in mind that the larger the delegation (15 or more members), the more complex the organization of the delegation’s activity will be. The main task of the demarcation commission is to draw up the final demarcation documents (OSCE 2017, 71). It is during this process that a model for marking out a state boundary is decided upon. One can use boundary markers consisting of one element to be erected right on the boundary, or three elements. The later model includes a center zero-offset monument (ZOM) that is erected directly on the boundary line along with boundary pillars erected at some distance on both sides of the boundary. These boundary markers are, as a rule, erected at turning points where the course of the state boundary changes direction; at spots where the boundary is crossed by railways, dams, and other structures; at transition points of the state boundary from the land section into water one and vice versa; within zones of active economic and other activities of the cross-border population; and where the visual identification of the state boundary is hindered (OSCE 2017, 76).

The transfer of the state boundary line from the delimitation map onto the terrain is the most important stage of state boundary demarcation. It is at this point that all inappropriately adopted decisions within the delimitation stage, errors, mistakes, unclear plotting of boundary line or discrepancies between the map and a boundary description create intractable problems. The transfer is carried out by a joint working group formed by the demarcation commission and consists of two national parts (OSCE 2017, 85).

The acceptance of the demarcated boundary along with state boundary demarcation summary documents (demarcation map, protocols of boundary markers, catalogue of boundary markers’ coordinates, state boundary description, summary protocol of the state boundary demarcation) are the last stage in the overall process and are carried out by the demarcation commission after clearing the state boundary strip, erecting, and coordinating boundary markers and preparing draft final documents of boundary demarcation within a section under acceptance. The OSCE advises carrying out the acceptance of a boundary in two stages: 1) by an expert group and 2) by the demarcation commission (OSCE 2017, 124-125). The summary documents on the state boundary demarcation, as a rule, come into force on the date of exchange of notifications about the completion of necessary domestic procedures mandatory for their approval, or on the date the last notification is received (OSCE, 134).

How Demarcation Drives Conflict

Several possible scenarios are likely to propel the involved parties toward conflict. In the first scenario, one or both sides refuse to follow the four steps in order. For instance, one party embarks on demarcation before a political agreement of delimitation has been reached. If one side considers the ground being marked as its own territory, the marking action is regarded as an act against its territorial integrity and thus an act of aggression, which in turn leads to opposition and countermeasures.

This is exactly what happened between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Right after the November 10 ceasefire statement that put an end to the 44-day war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan started marking the boundary unilaterally. In May 2021, Armenian authorities applied to the Collective Security Treaty Organization claiming that Azerbaijani border forces had entered Armenian territory near Lake Sev/Qaragöl. The CSTO refused to take any action (Kucera 2021a) whereas Azerbaijani authorities denied violating Armenian borders and explained that they were trying to determine the boundary, which had been impossible to do before due to the physical conditions in the region (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan 2021). Azerbaijani border forces returned to their positions before the situation turned into a crisis. In mid-November 2021, the most serious escalation since the end of the war broke out between Armenia and Azerbaijan, again around Lake Sev/Qaragöl. As a result of the skirmishes, dozens of troops were killed while others were injured or detained (Kucera 2021b).

In a second scenario, a delimitation agreement is signed but its terms are not followed adequately or the uncertainties within are exploited for the sake of acquiring a larger part of the border. Azerbaijan and Armenia have yet to agree on the terms of delimitation. Once the agreement is signed, one needs to observe whether they abide by the agreed terms.

It is also likely that adjacent states cannot reach an agreement due to reference to categorically different sources (e.g., maps or documents), which opens the way for territorial claims and pushes the parties towards dispute. A vivid example is Kyrgyz-Tajik border issues. The two countries have attempted to resolve the problem by creating border commissions but have not been able to come to an agreement as Tajikistan insisted on the 1924-1939 maps whereas Kyrgyzstan stuck to rather later maps of 1958-1959 (Kurmanalieva 2018). The dispute lingers to date and has recently escalated into a large-scale armed conflict (Buranelli, 2021). Since the USSR leadership made territorial multiple alterations within the union without taking into consideration demographic factors such as ethnic and cultural composition, the states formed following the collapse of the union found themselves in intractable territorial conflicts.

How Demarcation Drives Peace

When administered properly, demarcation may prevent escalation and contribute to the peace process in a number of ways. First of all, it follows an agreement of delimitation and proceeds accordingly with a clear reference. This is of utmost importance for putting legal responsibility on the parties and averting a political crisis. Second, it takes place with the collaboration of the commissions of the adjoining states, which prevents secret agendas, uncertainty, and thus insecurity. Third, it sustains uninterrupted communication and exchange between the sides as the process on the ground is agreed upon and excludes military involvement. This is crucial for the security of the borderline communities, as well. Fourth, the successful completion of demarcation means that the adjoining states do not have any territorial claims against each other. Last but not least, it inhibits adverse speculations and the spread of disinformation since it creates room for the public to be informed about what is taking place on the ground.

Recent history has witnessed numerous transformations from conflict to cooperation thanks to the successful completion of delimitation and demarcation. Kazakhstan’s experience in border politics has possibly been the best example among the former Soviet republics. The country has to a great extent finalized delimitation of boundaries with all neighbors and their demarcation (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan 2018). For instance, the Kazakh border with China had been a subject of conflict between the USSR and the People’s Republic of China prior to the collapse of the former. However, with the timely diplomatic maneuvers of Kazakh President Nazarbayev and thanks to the huge economic interests of both sides, the disputes were resolved with three delimitation agreements signed in 1994, 1997, and 1998. The latter document put an end to the territorial claims and the parties shared the disputed lands evenly (BBC 1998). Two years after the first agreement, the demarcation process commenced, which was finished in 2001 and formalized in 2002 with a joint protocol (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan 2018).

The Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan border is also worth elaboration. The process of delimitation started in 2000 and lasted two years. Although the parties reached an agreement for the major portion of the border, two villages—Bagys and Turkestanets—that were populated with ethnic Kazakhs but controlled by Uzbekistan became a source of dispute between the parties and led to several clashes (Razumov 2002). The border delimitation deal came into force in 2003. However, the border dispute failed to cease and continued throughout the year (Alibekov 2003). The dispute turned into border clashes several times by 2016. Nevertheless, with the change of leadership in Uzbekistan, the official position altered. The new president, Mirziyoyev, has been more ambitious to resolve the problems with the neighboring states (Goble 2020). Within the past two years, the two countries have shown considerable progress toward finalizing the demarcation process and launched cross-border projects. For instance, in March 2021, Kazakhstan inaugurated a Border Liaison Office on the Kazakh-Uzbek border to improve cross-border cooperation, security, and intelligence sharing (UNODC 2021). The two sides also established a corridor in 2021 to ease the access of pilgrims to holy sites (Kuandyk 2021). At the same time, the demarcation of the border continues with the regular meetings of the delegations to discuss the terms of the treaty of demarcation (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Uzbekistan 2021).

Another reference could be the Finland-Russia border and particularly the case of Karelia. As a former part of the Russian empire, modern-day Finland had a territorial dispute with the USSR and then the Russian Federation. The so-called Karelian question constituted the core of the issue, where a portion of the local population speaking a language closely related to Finnish was under Russian control (Joenniemi 1998). The issue gained additional significance with Finland becoming an EU member and thus becoming a frontier between the EU and Russia (Parot 2007, 3). Despite the scope of the disagreement between Finland and Russia, the sides agreed on the delimitation and demarcation of the boundary in 2007 and the demarcation works were completed between 2007 and 2016. The parties signed a treaty approving the boundary marks in June 2017 and agreed that they would discuss the validity of the demarcation every 25 years (National Land Survey of Finland 2017).

Main Challenges to the Delimitation and Demarcation of the Armenia-Azerbaijan Border

The ongoing boundary determination process between Armenia and Azerbaijan is clearly not one of those we have described above as the optimal sequence of actions facilitating peace. There are a number of factors that prevent the suggested sequence of actions.

To begin with, the primary barrier to delimitation and demarcation is political in nature. The actions taken on the ground, such as Azerbaijani forces crossing the Armenian border, are not congruent with the positions expressed by Armenian and Azerbaijani politicians after the previous meetings. This is to say that the parties have presumably adopted different agendas that are not stated openly or contradict the responsibilities they have taken on. Even after the creation of the commissions and their first meeting, the two parties are likely to still have incompatible positions on several issues related to delimitation. In addition, this stems from the vagueness of the agreements reached so far, such as the status of the Lachin corridor and the transport routes connecting Azerbaijan and Nakhichevan.

Although Armenia and Azerbaijan agreed to establish border commissions and the commissions held their first meeting, the second meeting agreed to be held in Moscow the following week has not taken place as of this writing. In addition, there seems to be a diversification of the third party, Russia, which was the primary mediator prior to the war with Ukraine. However, the EU is increasingly involved and seems to be willing to take Russia’s place. As a result of this ongoing shift, Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders met in Brussels under the auspices of the president of the European Council on 6 April 2022 (European Council 2022). Nevertheless, Russia’s presence is still visible as the second meeting of the commissions was scheduled to take place in Moscow and the third one to be held in Brussels again.

A related political issue is mutual recognition of the territorial integrity of the two states. Kucera (2022) argues that the Armenian side might be willing to compromise the idea of independence of the breakaway region for the sake of normalization of relations, provided that the human rights of the Armenian population of the region are guaranteed. This argument came out because of Pashinyan’s speech on April 13 at the National Assembly, during which he said:

I repeat, all our friends, close and not so close friends, expect us to surrender seven famous regions to Azerbaijan in one way or another and bring down our benchmark for the status of Artsakh. I am guilty for I did not tell our people that the international community unequivocally recognizes the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan, expects us to recognize it, and expect that the Azerbaijanis who left Karabakh should be fully involved in deciding the future of Nagorno-Karabakh… (The Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia 2022)

The speech caused domestic pressure on the Armenian leadership because it implied recognizing Nagorno-Karabakh as a territory of Azerbaijan. Although the Armenian prime minister is well aware that the international society is not likely to back Armenia against Azerbaijan and ignore the principle of territorial integrity, the increasing domestic political pressure of the opposition forced the Armenian government to step back from what the two sides agreed on at the Brussels meeting. The Azerbaijani foreign minister stated in mid-May that Azerbaijan had created the commission by the end of April whereas Armenia had failed to do so and kept postponing the date of the meeting between the two border commissions.[10] According to the Armenian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ararat Mirzoyan, Armenia had rejected to meet due to the absence of discussions regarding the status and security of Nagorno-Karabakh, and the human rights of its Armenian population.[11]

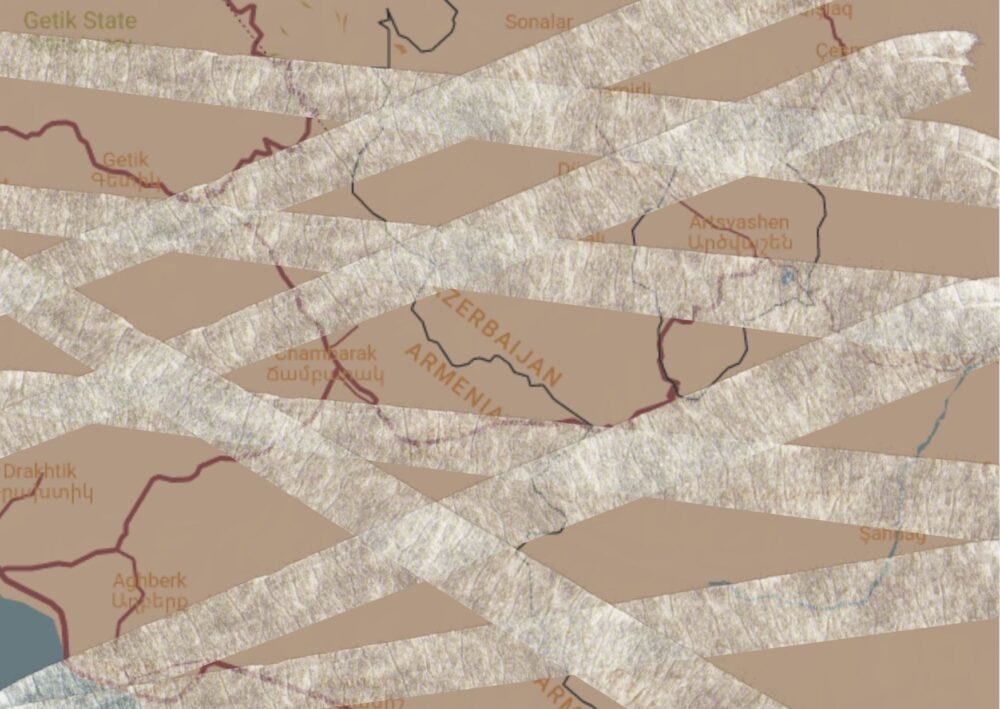

The technical hurdles to overcome are not insignificant. As discussed earlier, border commissions refer to various sources while establishing their national positions, including maps, previous administrative boundaries, and agreements. It is not an easy task to choose a reference document while determining the Armenia-Azerbaijan boundary and, more generally, boundaries between post-Soviet states. During the Soviet period, national boundaries mattered minimally as the republics in the union were virtually deprived of their national characters, such as sovereignty, independent governance, army, currency, as well as their borders. On the contrary, these vague borders took on a crucial role in the nation-building of the newly independent states, yet they lacked preciseness and became a subject of dispute due to clashing territorial claims (Levinsson 2006). The same is true for the Armenian-Azerbaijani boundary. Although the parties have agreed to take Soviet maps as a reference, only a few of those available can be helpful in terms of disputed zones where natural boundaries or ethnic divisions are unclear. It is known that Soviet military cartographers were assigned to map not only the states included in the union but also strategically important world cities with high precision (Miller 2017). Russian officials have stated that they would allow Armenia and Azerbaijan to use these maps if both requested to do so (news.am 2022).

The issue is not only how accurate the maps are but also the social repercussions of division according to those maps. People living near the boundary will be affected in one way or another. On the one hand, current uncertainty about where the boundary is creates insecurity among civilians living nearby. The issue is particularly critical for the Armenian population residing along the territories regained by Azerbaijan in the 44-Day War. Prior to the war, these people used the Azerbaijani territory for pasture but now they have lost their access to the resources vital for their livelihood. Just as Azerbaijanis living near the former line of contact used to risk their lives to cultivate the soil and run their daily errands (Abbasov & Jafarli 2007), some Armenian villagers and farmers unaware of the precise location of the boundary often cross the border and carry the risk of being a target of the border guards of the other side (Avedian 2021).

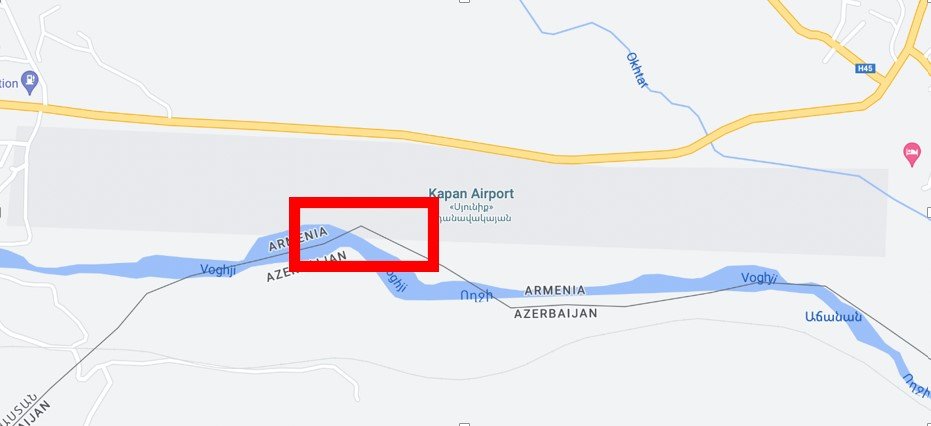

On the other hand, there is also uncertainty regarding what will happen to those who are bound to lose their houses and farmlands when a delimitation agreement is signed and the boundary is marked. Moreover, Armenian authorities had developed vast infrastructure without taking de jure borders into consideration. For instance, Balabanian (2021) argues that 116 Armenian cities and villages are as close as 5 km to the boundary with Azerbaijan and some parts of the infrastructure built in the last three decades, such as Kapan Airport, fall within Azerbaijani territories according to Soviet-era maps. Also, the road connecting Kapan and Syunik with the Goris districts of Armenia, which was built before the conflict erupted, runs through Azerbaijan in several parts. This caused no trouble during the Soviet period but now that Azerbaijan has restored control over its Qubadli district, Armenian vehicles have to pass Azerbaijani customs checkpoints (Cricchio 2021).

Having exclaves within the territory of the other side can be another matter of dispute. Exclaves are pieces of territory of one state that are surrounded by the territory of one or more other states. In other words, these regions have no direct ground connection to the state they belong to except through the territory of the state within which they are located. Nakhchivan is a typical example of an exclave as seen from Azerbaijan. There are five Azerbaijani exclave villages in Armenia—Karki to the West, Ashaghi Askipara and Yukhari Askipara to the northeast and Barkhudarli and Sofulu to the east—and one Armenian exclave village in Azerbaijan—Artsvashen to the west. The problem is that these exclaves have been under the control of the host states since the 1990s and no Armenians or Azerbaijanis live there although they have never been removed from the official maps. The two sides appear to agree that the future of the exclaves should be settled if delimitation and demarcation are to be completed (Khachatryan, 2022).

Policy Recommendations

In light of the aforementioned issues, we recommend the parties take measures to ensure a smooth completion of delimitation and demarcation. First of all, the high-level political leaders of the two sides must show willingness to further the progress achieved so far, particularly with regard to forming a Joint Border Commission. On April 11, 2022, the foreign ministers of Armenia and Azerbaijan had a phone call and discussed the issue (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan 2022), which should be regarded as a step forward since this was the first time since the end of the latest war that the parties have contacted each other directly.

Although the future of Nagorno-Karabakh has been the main source of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the sides are recommended to refrain from bringing up the issue as a prerequisite for delimitation and from trying to establish a connection between borders and the status of Nagorno-Karabakh. The two issues should be handled separately for the sake of achieving a negotiated result for both issues. The point is that bringing up the question of the status of Nagorno-Karabakh—Armenia’s insistence on independence or Azerbaijan’s no-status rhetoric—might endanger the process of delimitation and demarcation. On the contrary, the delimitation and demarcation of the Armenia-Azerbaijan border is crucial for the territorial integrity of the Republic of Armenia in that it is likely to eliminate the question of an existential threat from Azerbaijan.

In terms of the technical barriers listed above, the parties may make use of the topographical maps drawn up in the Cold War period, however without relying solely on them. We discussed above how maps are not referred to as the single most important source without accompanying documents. We do not know whether the maps offered by Russia are accompanied by thorough texts that provide a precise description of the boundary. It should also be acknowledged that over four decades have passed since those maps were prepared and there are new political and social realities on the ground. For the disputed parts of the border, the parties should agree on a mutually beneficial solution. For instance, the issue of Lake Sev/Qaragöl could be solved with the creation of a transboundary conservation site monitored by a joint body. According to UNESCO (2019), there are 21 such reserves around the world.

For the security of the residential sites in the proximity of the boundary, the best practice is the mirror withdrawal of the two sides’ military forces. It is obviously impossible to complete the demarcation of the boundary without any impact on the people living nearby. However, a human-centered approach should be taken. That is, borderland communities must be informed about the process of demarcation before its implementation. This would eliminate unwanted speculations such as one side committing aggression against the other. People need to be guaranteed that their property rights will not be disregarded. Moreover, those whose livelihood depends on the territory that falls on the other side according to the delimitation agreement should be compensated or allowed to retain their rights to use it, as in the case of the Russian-Finnish border agreement, for example. The noteworthy feature of the agreement is that Finnish reindeer herders are allowed to use the lands under Russian control as summer pastures (OSCE 2017, 15).

The problem of established infrastructure should be handled in a way that fosters the economic benefit of both sides. The Kapan-Goris Road and Kapan Airport do not need to be relocated. Rather, Armenia and Azerbaijan could both benefit from the capacity of these structures for the development of the territory destroyed during the 30 years of conflict. Moreover, these structures can contribute to local trade and consequently to the prosperity of people residing in the region. On the other hand, in order to ensure security and prevent cross-border crime, there must be increased safety measures, which requires completion of demarcation.

To find a common ground for the exclaves issue the key might be looking back at history. In the 1980s, at the outset of early violent acts, some Armenian and Azerbaijani villagers swapped their houses located in the territory of the other side. This is described as a completely voluntary solution, as the Azerbaijani mayor of the Qizil Shafag/Dzyunashogh village in Armenia came up with the idea and the locals accepted it. People agreed to maintain each other’s cemeteries so that they could pay a visit once a year, which have been protected to date on both sides (Huseynova, Hakobyan & Rumyantsev 2008; Furiong 2022). Land exchange rather than returning the control of these regions to their de jure owners could be a better solution for several reasons. Most importantly, the sides might attempt to militarize their exclaves, which in turn would endanger the civilians living in nearby villages such as Azatamut.

The village is located so close to the Azerbaijani exclaves of Askipara that Azerbaijani military posts could be seen with a naked eye prior to the 1990s war.

Moreover, the future of the Azerbaijani exclaves in Armenia matter due to the fact that several important roads pass through or near these settlements (Khachatryan 2022) including the Sarigyugh-Baghanis road to the northeast and Zangakhatun-Yeraskh to the southwest. The Armenian exclave Artsvashen in Azerbaijan is also crucial for the host country since its territory and the lake located in the village have been used by the population of the neighboring Azerbaijani villages as crop fields.

To summarize, delimitation and demarcation is usually a drawn-out, labor- and cost-intensive process. It requires political will, mutual compromise, and expertise. The result, however, will bring security and stability, thus contributing to the peace process.

Bibliography

“Announcement.” National security service. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://www.sns.am/en/press-releases/2020/12/20/announcement/523.

“Armenia MFA Issues Official Position over Demarcation Processes in Response to Ombudsman’s Inquiry.” armenpress.am, December 30, 2020. https://armenpress.am/eng/news/1039352.html.

“Armenians Displaced by Post War Demarcations – Armenia.” ReliefWeb, January 21, 2021. https://reliefweb.int/report/armenia/armenians-displaced-post-war-demarcations.

“Azerbaijani Military Throwing Stones at Civilian Car in Syunik Confirms the Urgent Need for a Security Zone.” Azerbaijani military throwing stones at civilian car in Syunik confirms the urgent need for a security zone , Ombudsman. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://www.ombuds.am/en_us/site/ViewNews/1613.

“Caucasus Live Map and News Today – Azerbaijan Armenia Georgia Incidents – Caucasus.liveuamap.com.” Caucasus Live map and news today – Azerbaijan Armenia Georgia incidents – caucasus.liveuamap.com. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://caucasus.liveuamap.com/.

“CSO Statement on Trilateral Negotiations.” Transparency.am. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://transparency.am/en/media/news/article/3110.

“Latest Developments: Application of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Armenia V. Azerbaijan): International Court of Justice.” Latest developments | Application of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Armenia v. Azerbaijan) | International Court of Justice. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/180.

“Orbeli Analitical Research.” Accessed October 7, 2022. https://orbeli.am/hy/post/863/2021-05-17/%D5%8D%D6%87%20%D5%AC%D5%AB%D5%B3%D5%A8%D5%9D%20%D5%AD%D5%B8%D6%80%D5%B0%D6%80%D5%A4%D5%A1%D5%B5%D5%AB%D5%B6%20%D6%84%D5%A1%D6%80%D5%BF%D5%A5%D5%A6%D5%B6%D5%A5%D6%80%D5%B8%D6%82%D5%B4?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=pmd_7a24b2ada7ef192383a1dce3ecf976dd3b7cc7f9-1628332481-0-gqNtZGzNAuKjcnBszQc6.

“Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s Speech at the National Assembly during the Discussion of the Performance Report of the Government Action Plan for 2021.” Հայաստանի Հանրապետության վարչապետ. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://www.primeminister.am/en/statements-and-messages/item/2022/04/13/Nikol-Pashinyan-Speech/.

“The Right to Drinking Water of the Residents of Meghri Community Is Violated by the Deliberate Actions of the Azerbaijani Armed Forces.” The right to drinking water of the residents of Meghri community is violated by the deliberate actions of the Azerbaijani armed forces , Ombudsman. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://www.ombuds.am/en_us/site/ViewNews/1510.

“Հայաստանի և Ադրբեջանի Փոխվարչապետերի Հանդիպումը.” Հայաստանի Հանրապետության արտաքին գործերի նախարարություն. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://www.mfa.am/hy/press-releases/2022/05/24/Arm_Az_commission/11467.

“Նոյեմբերի 9–ի Փաստաթուղթը Շատ Վատն է, Եթե Այդ Փաստաթուղթն Ամբողջությամբ Բացահայտեն, Ապա Չեմ Կարծում, Որ Հայաստանի Ղեկավարը Կկարողանա Մտնել Իր Տուն. Մովսես Հակոբյան (Տեսանյութ).” Լուրեր Հայաստանից – Թերթ.am. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://www.tert.am/am/news/2022/06/10/movses-hakobyan/3811094?fbclid=IwAR04p-xUapz_Iw7W9iwBLa1jv1135mMhNzm32ypBodInSIlAplug0pfNzMI.

“Սև Լիճը Վիճելի Տարածք Չէ.” armenpress.am. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://armenpress.am/arm/news/1052781.html.

“Վարչապետ․ Սահմանազատման Հանձնաժողովը Որևէ Կապ Չունի ԼՂ Խնդրի Հետ.” PanARMENIAN.Net. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://www.panarmenian.net/arm/news/300887/.

22:53:00, 2021-01-30. “Azerbaijani Military Firing near Syunik Villages, Says Armenian Human Rights Defender.” Hetq.am, January 30, 2021. https://hetq.am/en/article/126886.

23:44:00, 2021-05-27. “Border Conflict: U.S. State Department ‘Concerned’ over Detention of Armenian Soldiers by Azerbaijan.” Hetq.am, May 27, 2021. https://hetq.am/en/article/131455.

3272 – azərbaycan Respublikası Ilə Ermənistan Respublikası Arasında dövlət sərhədinin delimitasiyası üzrə Dövlət Komissiyasının Yaradılması Haqqında. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://e-qanun.az/framework/49654?fbclid=IwAR0Tu48H2w1HgpSa5SCOLQx-Cc5JgGa_5zVV9wWtcSSSbTWjRGIcOJu46HA.

Abbasov, Idrik, and Bala Jafarli. 2007. Azerbaijan: Farming in no-man’s land. July 5. https://reliefweb.int/report/azerbaijan/azerbaijan-farming-no-mans-land.

Alibekov, Ibragim. 2003. Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan clash over border policy. September 29. https://www.refworld.org/docid/46c58efec.html.

Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

APA. 2022. Azerbaijan is ready to begin unconditional delimitation process with Armenia. February 4. https://apa.az/en/foreign-policy/azerbaijan-is-ready-to-begin-unconditional-delimitation-process-with-armenia-367615.

ARKA News Agency. 2022. Azerbaijan rejects Armenian proposals on border delimitation, but negotiations continue- FM Mirzoyan says. February 3. http://arka.am/en/news/politics/azerbaijan_rejects_armenian_proposals_on_border_delimitation_but_negotiations_continue_fm_mirzoyan_s/.

Avedian, Lillian. 2021. “Sharing pastures with the enemy” in Armenia’s borderlands. February 17. https://armenianweekly.com/2021/02/17/sharing-pastures-with-the-enemy-in-armenias-borderlands/.

Avetisyan, Ani. 2021. Nagorno-Karabakh civilian shot dead in apparent ceasefire violation. October 11. https://oc-media.org/nagorno-karabakh-civilian-shot-dead-in-apparent-ceasefire-violation/.

AzerTac. 2022. Foreign Ministry: Azerbaijan has announced basic principles proposed for establishment of relations with Armenia. March 14. https://azertag.az/en/xeber/Foreign_Ministry_Azerbaijan_has_announced_basic_principles_proposed_for_establishment_of_relations_with_Armenia-2052467.

Badalian, Susan. “Armenian Government Vows Bypass Roads in Border Region.” “Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն” ռադիոկայան. Ազատություն ռ/կ, February 11, 2021. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31097928.html.

Balabanian, Pakrad Sarkis. 2021. Historic Secret Soviet Maps Decide The Faith of a Nation. January 7. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f22c38d694c5498882e850848b8fc795.

BBC. 1998. China ends Kazakh border dispute. July 4. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/126276.stm.

Crawley, Heaven. 2016. “Managing the Unmanageable? Understanding Europe’s Response to the Migration ‘Crisis’.” Human Geography 9 (2): 13–23. Accessed 3 18, 2022. https://hugeog.com/managing-the-unmanageable-understanding-europes-response-to-the-migration-crisis.

Cricchio, Emilio Luciano. 2021. New highway crisis emerges as Azerbaijan sets up checkpoints on strategic Armenian road. November 11. https://www.civilnet.am/en/news/639277/new-highway-crisis-emerges-as-azerbaijan-sets-up-checkpoints-on-strategic-armenian-road/.

Diener, Alexander C, and Joshua Hagen. 2012. Borders: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

email, Siranush GhazanchyanSend an, Siranush Ghazanchyan, and Send an email. “Impossible to Demarcate Armenia’s State Border on the Basis of Google Maps – Ombudsman.” Public Radio of Armenia, December 14, 2020. https://en.armradio.am/2020/12/14/impossible-to-demarcate-armenias-state-border-on-the-basis-of-google-map-ombudsman/.

European Council. 2022. Statement of European Council President Charles Michel following the Second Trilateral Meeting with President Ilham Aliyev and Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan. April 6. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/04/06/statement-of-european-council-president-charles-michel-following-the-second-trilateral-meeting-with-president-ilham-aliyev-and-prime-minister-nikol-pashinyan/.

Fukuyama, Francis. 1989. “The End of History?” The National Interest 16: 3–18.

Furiong, Ray. 2022. Village Swap: How Armenians and Azeris Switched Homes Amid 1980s Ethnic Tension. February 13.

Goble, Paul. 2020. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan Likely to Sign Border Treaty Soon to Avoid Worse Problems. March 26. https://jamestown.org/program/kazakhstan-and-uzbekistan-likely-to-sign-border-treaty-soon-to-avoid-worse-problems/.

Greenhill, Kelly M. 2016. “Open Arms Behind Barred Doors: Fear, Hypocrisy and Policy Schizophrenia in the European Migration Crisis.” European Law Journal 22 (3): 317-332.

Huseynova, Sevil, Arsen Hakobyan, and Sergey Rumyantsov. 2008. Beyond the Karabakh Conflict: The Story of Village Exchange. Tbilisi: Heinrich Böll Stiftung South Caucasus.

JAMNews. 2022. Armenia proposed border demarcation concept to Azerbaijan – What went wrong? January 21. https://jam-news.net/armenia-proposed-border-demarcation-concept-to-azerbaijan-what-went-wrong/.

Joenniemi, Pertti. 1998. “The Karelian Question: On the Transformation of a Border Dispute.” Cooperation and Conflict 33 (2): 183-206.

Khachatryan, Arthur. 2022. Enclaves – islands of Armenian-Azerbaijani confrontation. March 21. https://jam-news.net/enclaves-islands-of-armenian-azerbaijani-confrontation/.

Kuandyk, Abira. 2021. New Tourist Corridor to Connect Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan’s Main Pilgrimage Sites. January 27. https://astanatimes.com/2021/01/new-tourist-corridor-to-connect-kazakhstan-and-uzbekistans-main-pilgrimage-sites/.

Kucera, Joshua. 2021a. Armenia and Azerbaijan in new border crisis. May 14. https://eurasianet.org/armenia-and-azerbaijan-in-new-border-crisis.

Kucera, Joshua. 2021b. Heavy fighting breaks out between Armenia and Azerbaijan. November 16. https://eurasianet.org/heavy-fighting-breaks-out-between-armenia-and-azerbaijan.

Kucera, Joshua. 2022. Armenia signals willingness to cede control over Karabakh. April 1. https://eurasianet.org/armenia-signals-willingness-to-cede-control-over-karabakh.

Levinsson, Claes. 2006. “The Long Shadow of History: Post-Soviet Border Disputes—The Case of Estonia, Latvia, and Russia.” Connections 5 (2): 98-110.

Miller, Greg. 2017. The Soviet Military Program that Secretly Mapped the Entire World. October 13. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/maps-soviet-union-ussr-military-secret-mapping-spies.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan. 2018. “Delimitation and Demarcation of State Border.” October 1. https://web.archive.org/web/20200122102014/http://mfa.gov.kz/en/content-view/delimitatsiya-i-demarkatsiya-gosudarstvennoj-granitsy.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan. 2021. “No:165/21, Information of the Press Service Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan.” https://mfa.gov.az/en/news/no16521-information-of-the-press-service-department-of-the-ministry-of-foreign-affairs-of-the-republic-of-azerbaijan.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan. 2022. No:174/22, Information of the Press Service Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan on telephone conversation of Minister Jeyhun Bayramov with Foreign Minister of Armenia Ararat Mirzoyan. April 11. https://mfa.gov.az/en/news/no17422.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Uzbekistan. 2021. В г. Алматы состоялось заседание Правительственных делегаций Узбекистана и Казахстана. October 29. https://mfa.uz/ru/press/news/2021/v-g-almaty-sostoyalos-zasedanie-pravitelstvennyh-delegaciy-uzbekistana-i-kazahstana—30712.

National Land Survey of Finland. 2017. Boundary demarcation on the border between Finland and Russia. June 20. https://www.maanmittauslaitos.fi/en/topical_issues/boundary-demarcation-border-between-finland-and-russia.

Newman, David. 2001. “Boundaries, Borders, and Barriers: Changing Geographic Perspectives on Territorial Lines.” In Identities, Borders, Orders: Rethinking International Relations Theory, edited by Mathias Albert, David Jacobson and Yosef Lapid, 137-152. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

news.am. 2022. Lavrov: We are in favor of soonest start of Armenia-Azerbaijan border demarcation. January 14. https://news.am/eng/news/682015.html.

OSCE. 2017. “Delimitation and Demarcation of State Boundaries: Challenges and Solutions.” Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. December 19. https://www.osce.org/secretariat/363466.

Parot, Jocelyn. 2007. “Outer Borders, Inner Boundaries in Finland. The Reconstructed Russian Border and the Changing Geography of Memory.” Borders of the European Union: Strategies of Crossing and Resistance. HAL Open Science. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01170405/document.

Prescott, Victor, and Gillian D Triggs. 2008. International Frontiers and Boundaries: Law, Politics and Geography. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

President of Russia. 2021. Statements by leaders of Russia, Azerbaijan and Armenia following trilateral talks. November 26. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67203.

President of the Republic of Azerbaijan. 2021. A trilateral meeting was held among Russian President Vladimir Putin, President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev and Prime Minister of Armenia Nikol Pashinyan in Sochi. 26 November. https://president.az/en/articles/view/54420.

Razumov, Yaroslav. 2002. Kazakhstani-Uzbek border flap threatens to stoke regional tension. February 26. https://www.refworld.org/docid/46c58edd465.html.

Reuters. 2017. Azeri woman and child killed by Armenian forces near Nagorno-Karabakh boundary: defense ministry. July 5. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-armenia-azerbaijan-conflict-idUSKBN19Q1VG.

Tatikyan, Sossi, and By. “2021 Snap Elections in Armenia: Internal and External Security Risks: Heinrich Böll Stiftung: Tbilisi – South Caucasus Region.” Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, June 19, 2021. https://ge.boell.org/en/2021/06/19/2021-snap-elections-armenia-internal-and-external-security-risks.

Technologies, Peyotto. “Գեղարքունիքում Որտեղ է Դիրքավորված Ադրբեջանական Զու-ն. Միպ-ը Ներկայացրեց Արտահերթ Զեկույցը․ ՏԵՍԱՆՅՈՒԹ.” factor.am. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://factor.am/436609.html.

Technologies, Peyotto. “Գնում Եք Դեմարկացիա Անելու Մի Երկրի Հետ, Որն Էթնիկ Զտո՞Ւմ է Իրականացնում Արցախում. Արամ Վարդևանյան․ ՏԵՍԱՆՅՈՒԹ.” factor.am. Accessed October 7, 2022. https://factor.am/496697.html.

UNESCO. 2019. Transboundary biosphere reserves. May. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves/transboundary-biosphere-reserves/.

UNODC. 2021. UNODC supports the opening of a new Border Liaison Office and computer-based training class on the Kazakh-Uzbek border. March 30. https://www.unodc.org/centralasia/en/news/unodc-supports-the-opening-of-a-new-border-liaison-office-and-computer-based-training-class-on-the-kazakh-uzbek-border.html.

Նալբանդյան, Նաիրա “Երևանը Չի Հստակեցնում, Թե Ինչ Օրակարգով է Փաշինյանը Մեկնում Ալիևի Հետ Բանակցելու.” “Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն” ռադիոկայան. Ազատություն ռ/կ, May 20, 2022. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31860264.html.

ռ/կ, «Ազատություն» “Արցախի Խորհրդարանը Հայաստանի Իշխանություններից Պահանջում է Հրաժարվել ‘Աղետալի Դիրքորոշումից.’” “Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն” ռադիոկայան. Ազատություն ռ/կ, April 14, 2022. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31803753.html.

ռ/կ, «Ազատություն» “Հայաստանում և Ադրբեջանում Ստեղծվում Են Երկու Երկրների Միջև Սահմանազատման և Սահմանային Անվտանգության Հարցերով Հանձնաժողովներ.” “Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն” ռադիոկայան. Ազատություն ռ/կ, May 24, 2022. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31864028.html.

ռ/կ, «Ազատություն» “Հայտնի է Հայաստան-Ադրբեջան Սահմանազատման Հանձնաժողովի Կազմը: Լրատվական Կենտրոն: Մայիսի 23. 2022.” “Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն” ռադիոկայան. Ազատություն ռ/կ, May 24, 2022. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31864899.html.

Սահակյան, Նանե “Սահմանազատման և Սահմանային Անվտանգության Հարցերով Հանձնաժողովները Կգլխավորեն Մհեր Գրիգորյանն Ու Շահին Մուստաֆաևը.” “Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն” ռադիոկայան. Ազատություն ռ/կ, May 24, 2022. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31864830.html.

Սարիբեկյան, Գայանե “Հայ-Ադրբեջանական Հանձնաժողովի Առաջին Հանդիպումը Կառուցողական է Եղել. Նախարար.” “Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն” ռադիոկայան. Ազատություն ռ/կ, June 1, 2022. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31878593.html.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/05/23/press-statement-by-president-michel-of-the-european-council-following-a-trilateral-meeting-with-president-aliyev-of-azerbaijan-and-prime-minister-pashinyan-of-armenia/

[2] https://e-qanun.az/framework/49654?fbclid=IwAR0Tu48H2w1HgpSa5SCOLQx-Cc5JgGa_5zVV9wWtcSSSbTWjRGIcOJu46HA, https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31864830.html

[3] https://mfa.gov.az/en/news/no25022

[4] https://asbarez.com/csto-called-out-for-its-lackluster-response-to-yerevans-appeal-for-assistance

[5] https://armenpress.am/eng/news/1039352.html

[6] https://www.aravot.am/2022/05/20/1269226/, https://www.panorama.am/am/news/2022/05/22/%D5%93%D5%A1%D5%B7%D5%AB%D5%B6%D5%B5%D5%A1%D5%B6-%D4%B2%D6%80%D5%B5%D5%B8%D6%82%D5%BD%D5%A5%D5%AC/2685404.

[7] https://factor.am/496697.html.

[8] https://www.primeminister.am/en/videos/item/b6Kl-dRWQ3Q/, https://www.panarmenian.net/arm/news/300887/.

[9] https://www.aravot.am/2020/08/14/1129354/, https://1tv.ge/lang/am/news/nikol-phashinyan-arcaxeh-hayastan-e-ev-verj/.

[10] https://report.az/xarici-siyaset/azerbaycan-serhedlerin-delimitasiyasi-ile-elaqedar-komissiyanin-terkibi-ile-bagli-ermenistana-teklifler-verib/

[11] https://www.civilnet.am/en/news/662078/mirzoyan-visits-brussels-to-talk-karabakh-as-yerevan-and-baku-seem-deadlocked-over-56-plan-border-commission/