Stories

25 Mar 2018

The Azerbaijani Heritage of Tbilisi: Forgotten and Tempered

Georgian Azerbaijanis have lived in Georgia for several centuries. According to the population census of 2014, Azerbaijanis comprise 6.3 percent of the Georgian population[1]. Georgian Azerbaijanis mainly live in the regions of Kvemo Kartli, Kakheti, Shida Kartli, and in the capital city of Tbilisi. Tbilisi in particular has played an important role for the cultural development of the Georgian Azerbaijanis and today is home to important heritage sites. However, many of these sites face challenges of oblivion and disuse. We have visited and explored three heritage sites – the Azerbaijani theatre of Tbilisi, the house of writer Mirza Fatali Akhundzade, and the publishing house of Mirza Jalil Mammadguluzade. While the Azerbaijani theatre suffers from a lack of funding and renovation; the house of Mirza Fatali has faced a renovation project that did not reflect its original spirit. The publishing house of Mirza Jalil is hanging in the air expectant of its own project.

The Azerbaijani Theater of Tbilisi: Struggle for Existence

The windows of the theater overlooking the yard. Photo Credits: Ilkin Hasanov.

The Azerbaijani theatrical tradition in its European variety started in the second half of the 19th century largely as the staging of Mirza Fatali Akhundzade’s comedies in the theaters of Tbilisi and Baku. While the first performances were in Russian, in 1872, a troupe of amateur actors in Tbilisi performed “The Story of the Vezir of the Khan of Lankaran” by Mirza Fatali Akhundzade in Azerbaijani. In 1909, the first performance of what would later become the Azerbaijani theatre of Tbilisi was held in the caravansary of the merchant Haji-Hashim Mardanov. Inspired by the success of the first performances, the merchant gave the present-day building of the theatre, located on Vakhtang Gorgasali Street, to its permanent use. In 1922, the theater acquired an official status and was named the Tbilisi State Azerbaijani Drama Theater of Tbilisi. Throughout years theatrical and cinematographic giants such as Mirzali Abbasov, Ibrahim Isfahanli, Pamphylia Tanailidi, Alekper Seyfi, Mohsun Sanani, Ulvi Radzhab, and others performed on its stage. Various Azerbaijani plays as well as many from around the world were staged in the Azerbaijani language in this theatre. In 1947, the theatre was shut down and resumed activities only at the end of the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s. Since 2004, this significant cultural monument carries the name of Heydar Aliyev. However, the Tbilisi State Azerbaijani Drama Theatre named after Heydar Aliyev is in a very deplorable state nowadays.

The photos cannot fully convey the exact shape of the building. The walls are old and rusty, crumbling down here and there. The floors are lined with linoleum to cover the holes in it. The costumes used by the actors are shabby and scattered around; the equipment important for the theatre needs serious repair. The government of Georgia renovated the roof, as in many other parts of old Tbilisi, to build a glittering façade for the cityscape especially well observed through video recording with drones. But the drones do not film the inside…

The building of the theater originally covered 3,200 square meters. According to Varlam Nikoladze, the current director of the theatre, displaced persons in need of housing moved into the building and later privatized most of the building. Now the theatre has only 800 square meters left. It has the lowest annual budget among the theatres in Georgia. The annual budget is just above 100,000 Georgian Lari, which is barely enough to cover the salaries for the actors who receive 200 Lari per month. As for the rehearsals, they take place in the most preserved parts of the theatre, the small rehearsal stage and Nikoladze’s office. If not for the devotion of the actors, the theatre could not have survived until now. Many national and international institutions have promised to help, but nothing came through so far. According to Varlam Nikoladze, it’s almost a year that he has been fighting for the survival of the theater, but the results are not so promising.

The hallway of the theater. Photo Credits: Ilkin Hasanov.

Some of the props and furniture. Photo Credits: Ilkin Hasanov.

The House of Mirza Fatali Akhundzade: Once a Shelter for Intellectuals, Now Just a Glittering Residence

The same Mirza Fatali Akhundzade, known also as Akhundov, whose comedies set the base for Azerbaijani dramaturgy has a house in Tbilisi located on the same street as the theater. Mirza Fatali was an Azerbaijani writer, philosopher, and is considered the founder of Azerbaijani dramatic art. He lived in different parts of south Azerbaijan till he was 13. In 1832, Mirza Fatali moved to Ganja to study logic and theology as a student of the famous poet Mirza Shafi Vazeh. In 1834, he moved to Tbilisi. Here he was appointed interpreter of oriental languages at the civil affairs section in the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire, where he worked until his death. Mirza Fatali is known by the crucial role he played in the formation of Azerbaijani dramaturgy. Between 1850 and 1855, Mirza Fatali wrote six comedies in Azerbaijani. Those comedies made Mirza Fatali the founder of Azerbaijani dramaturgy and the first dramaturg working in a Turkic language.

Mirza Fatali built his house in Meidan, one of the oldest neighborhoods of Tbilisi, where he lived until the last days of his life. This house has been functioning as a museum since 1982. During Mirza Fatali’s life, this house served as a gathering place for many intellectuals that held literary discussions and poetry evenings here. In 2012, for Mirza Fatali’s 200th anniversary, the building was completely renovated.

The renovation works were carried out by the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR). Now this place bears the status of “Museum of Azerbaijani Culture” named after Mirza Fatali Akhundov. It houses an art gallery and a library as well as a café and a wine cellar. Even though the building is now shining and glittering, it has lost its original appearance and spirit. Perhaps the place that better preserves Akhundov’s memory is his tomb in the National Botanical Garden of Georgia that expanded in the mid-20th century to include the cemetery of Tbilisi, where he was buried.

The Publishing House of Molla Nasreddin: The Tragedy of the Future of Satire

“The Magazine that Almost Changed the World”[2], “When Satire Conquered Iran”[3], “How Muslim Azerbaijan Had Satire Years before Charlie Hebdo”[4] – these are some of the headlines from influential magazines and newspapers describing the Molla Nasreddin[5] magazine. Molla Nasreddin was an eight-page Azerbaijani satirical magazine that became very influential “across the Muslim world; from Morocco to India”. Many admire but few know that Molla Nasreddin was first published in Tbilisi (from 1906 to 1917) and only after that the publication was moved to Tabriz (in 1921) and Baku (from 1922 to 1931).

We talked to historical researcher and writer Mirza Mammadoghlu about the story of how Molla Nasreddin came into being. During the 19th century, when the Caucasus Viceroyalty was established in Tbilisi, the city became the literary cultural center of the region. Azerbaijani intelligentsia were also visiting Tbilisi. Mirza Jalil Mammadguluzade, one of the greatest Azerbaijani writers and innovators, was one of them. A generation younger than Mirza Fatali, Mirza Jalil also first settled in Meidan. At that time, this part of the city was inhabited by the local Muslim community. Similar to Mirza Fatali, Mirza Jalil strived to transform and modernize his community, yet unlike Mirza Fatali he chose a more radical approach. Due to Mirza Jalil’s satiric attitude to Islam, he was not welcomed in his neighborhood. After his first attempt to publish the Molla Nasreddin magazine, he faced aggression from the local community. Mirza Jalil had to move to Davudovskaya Street (nowadays Besiki Street), which during that period was also called Sheikh Sanan Street in Azerbaijani. This house on Davudovskaya street became a home, shelter, and work space for Mirza Jalil and many others, who could boldly criticize politics, religion, colonialism, education (or lack thereof), and the oppression of women.

The Molla Nasreddin magazine had a profound impact on the intellectual environment of its time. Education was indeed one of its themes; its editors and publishers were very aware of the fact that most of the community was illiterate at that time. It strove to communicate its message to audiences through the medium of illustrations. Yet text and its graphic component were also an important part of the magazine. Published exclusively in Azerbaijani, it transitioned from using Arabic script to Latin and advocated for this reform.

One of the greatest supporters of Mirza Jalil was Ismail Hakki who was a typography worker. When Mirza Jalil was traveling around, all the heavy work of the Molla Nasreddin magazine was handed over to him. Some of the editions of Molla Nasreddin were published under Ismail Hakki’s supervision.

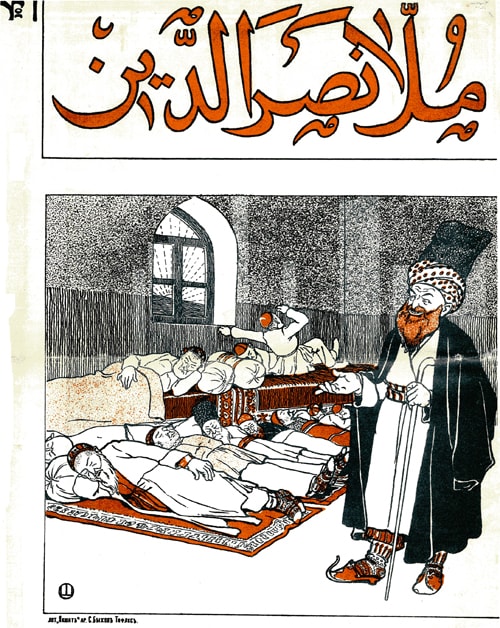

The cover of the first issue of Molla Nasreddin, published on April 7, 1906, referencing a verse from the poet Ṣāber: “Don't wake them, let them sleep”. Photo Source: Encyclopædia Iranica.

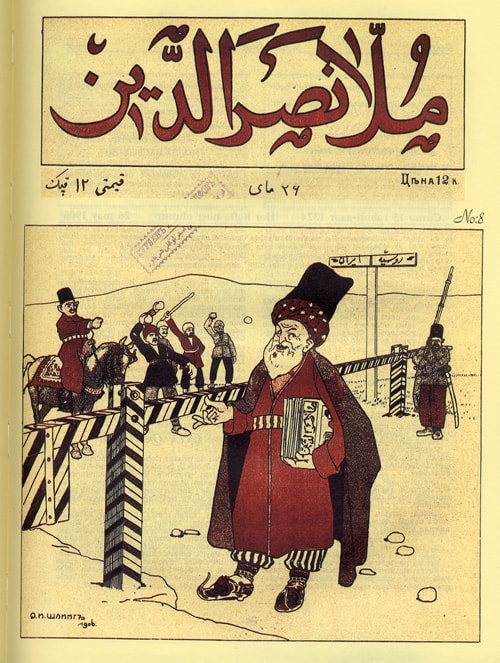

The cover of Molla Nasreddin published on May 26, 1906, showing the magazine’s arrival at the Iranian border. Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons.

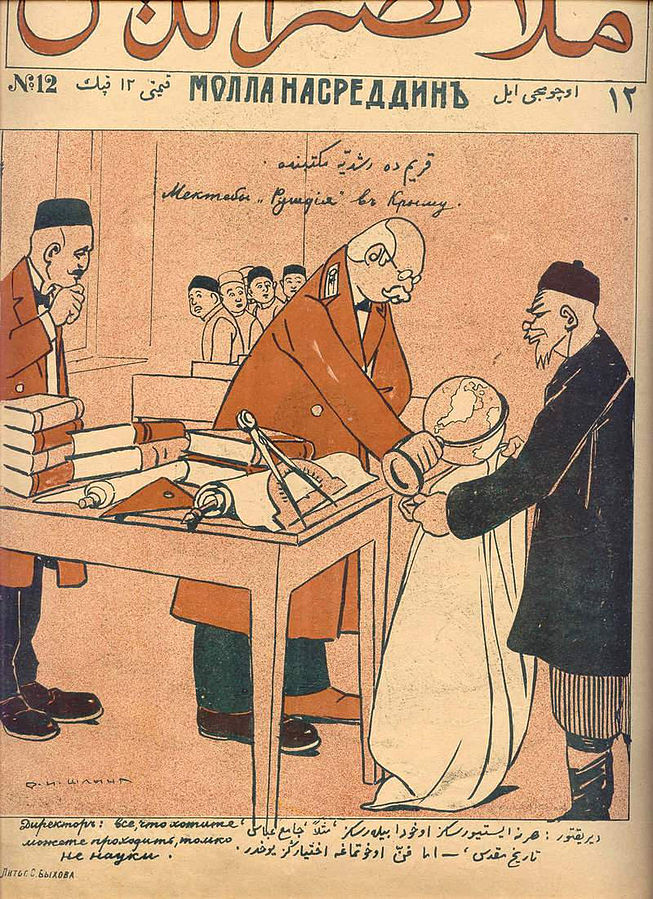

The cover of a 1909 issue of Molla Nasreddin picturing the filtering of what is permitted to be taught at a Rushdiyya School in Crimea. Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons.

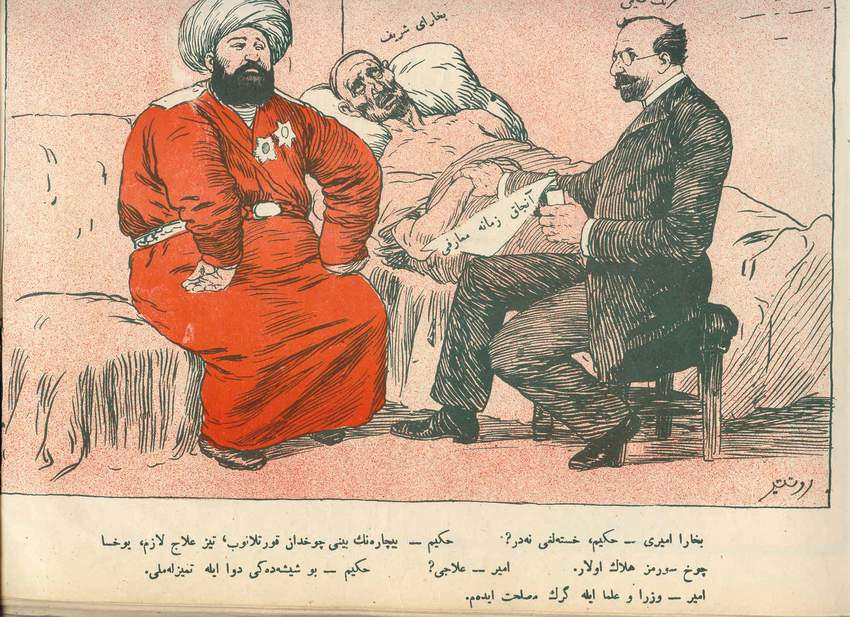

A caricature from Molla Nasreddin exposing the lack of professionalism among doctors. Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons.

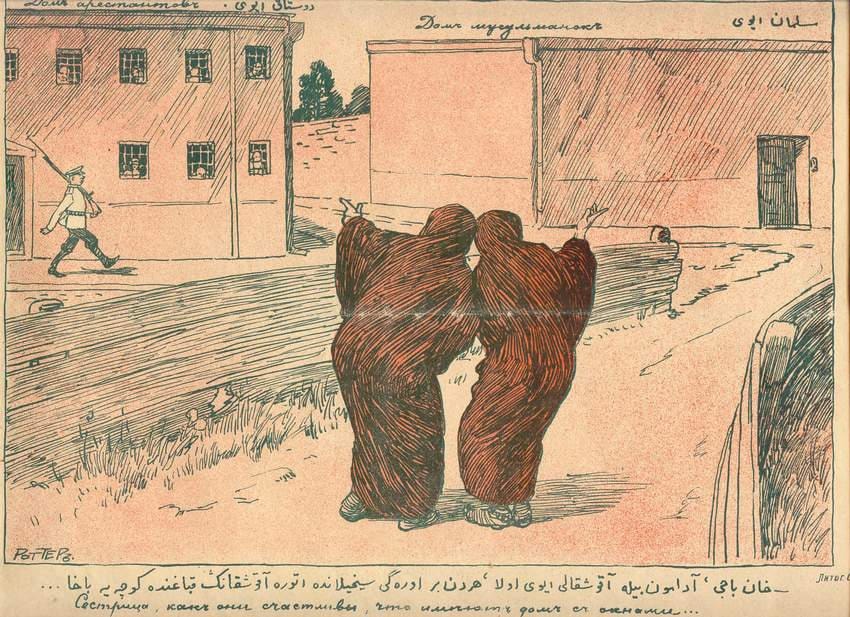

A caricature from Molla Nasreddin showing that while prisons have windows, the houses of Muslim women don’t. The caption reads “Sister, look how lucky they are: they have windows!”. Photo Source: Zerrspiegel.

What Future for These Heritage Sites?

The stories behind these sites of Azerbaijani heritage of Tbilisi are fascinating yet forgotten. The sites themselves are confined to oblivion or transformed in ways that steal their original character. Unfortunately, neither the government nor the community have stood up to their protection, preservation, or proper restauration. It remains to be seen if the renovation project that Mirza Mammadoghlu referred to will follow the path of Mirza Fatali’s house undergoing a makeover that will temper with its history and spirit or it will be confined to oblivion similar to the Azerbaijani theater. Perhaps, it will have better luck than both and will regain the acknowledgment and treatment that it deserves as a heritage site.

Footnotes

[1] National Statistics Office of Georgia. 2016. 2014 General Population Census. April 28. Accessed September 6, 2017. http://www.geostat.ge/cms/site_images/_files/english/population/Census_release_ENG_2016.pdf.

[2] Minkel, Elizabeth. 2011. “The Magazine that Almost Changed the World.” The New Yorker. May 26. Accessed November 26, 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-magazine-that-almost-changed-the-world.

[3] The New York Review of Books. 2012. When Satire Conquered Iran. 18 September. Accessed November 11, 2017. http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2012/09/18/when-satire-conquered-iran-molla-nasreddin/.

[4] Khalilova, Konul. 2015. “How Muslim Azerbaijan Had Satire Years Before Charlie Hebdo.” BBC. February 28. Accessed November 26, 2017. How Muslim Azerbaijan had satire years before Charlie Hebdo.

[5] The name of the magazine was inspired by a character famous for his anecdotes and present in the folklore of the peoples of the Middle East and Central and South Asia.

* This story has been produced with support from the US Embassies in the South Caucasus. The opinions expressed in the publication reflect the point of the view of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the US Embassies.

** This story is part of a series on the heritage of minority populations in the countries of the South Caucasus. Another story from the series is about the Armenian heritage of Tbilisi

Comments

Теймур Кулиев

14 Mar 2021

В период с 1852 по 1853 год комедия с успехом ставилась на русской сцене в Тифлисе. 10 (22) марта 1873 года эта комедия была избрана для первого азербайджанского любительского спектакля, поставленного в Баку.