Stories

27 Sep 2022

My Ghost, My Enemy

I was 21 when I first met an Azerbaijani. It was a short Erasmus+ program in Georgia. There were participants from seven countries, including Armenia and Azerbaijan. I remember sitting there in the conference room and looking at the Azerbaijani guy in front of me. He was taking notes, asking questions to the trainers that I was interested in as well, scratching his head, smiling, and there were two contradicting thoughts in my mind: “He is not a monster, he is just a guy, he looks like one of my friends” and then “he is Azerbaijani”. I only knew Azerbaijanis as people who are capable of cutting the heads of Armenians, who want to kill every single Armenian they meet. That was what I was told to believe all my life.

The borders between Armenia and Azerbaijan have been closed since the first Nagorno Karabakh war (1991-1994). This is one of the longest unresolved conflicts from the former USSR and the Armenian-Azerbaijani line of contact is one of the most heavily militarized in the world. On both sides generations grew up isolated from each other, having no understanding whatsoever about their neighboring society and in most cases taught only the most inhuman things about those living on the other side of the border.

It took me years of self-education, different programs outside my country, two years in a Masters program in Georgia with Azerbaijani group mates and two dialogue programs on the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict to come to the point not to have any negative feelings while hearing the word “Azerbaijani”.

I wonder now how long it would take for each and every person in our societies. Or would everyone be able to overcome this hatred towards each other?

During the last war in 2020, I had moments when I wished I didn’t know any Azerbaijani. It would be easier, I thought, to maintain a simplistic us-versus-them worldview; the good guys and the bad guys.

But instead I felt as if I was someone who, by some magic, appeared in another reality and had discovered a whole new other world and came back. Was I alone in my transformation? Absolutely not. I started reaching out to the people like me from both sides, those who I already knew and those who I got to know during the war.

There was Jamal , a 35 year old Azerbaijani musician and activist whose criticism towards the corrupt regime in Azerbaijan got him detained and eventually forced to exile. Jamal now lives in Germany. I saw his post on Facebook in July 2020, two months before the war, when the clashes started on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border. In his post he was talking about the time when he was playing at an open stage in Ukraine. At some point another guy joined him, they started playing several songs together, and the last one was “Soldat” (Soldier) by 5nizza (the song describes a soldier’s life and its cruelty). They played and sang it together, and people in the audience loved it. After it was over, they reached to hug each other, and he asked that guy where he was from. “From Armenia” he answered.

Later when I talked to Jamal over a video call he described this as a moment when he finally could get rid of those brutal pictures that were put in his head from a very young age. He says that when the full-scale war started, two months after he created the post, the Armenian guy who he was talking about in his post lost his nephew in the war. “He called me crying and said: you are the only person I know who would understand me”.

Jamal had his position very open on social media, being against the war and talking about how the hatred propaganda influenced both societies. He describes the anniversary of Khojaly massacres, (According to Human Rights Watch more than 200 Azerbaijani civilians and armed force was killed on 26th of February, 1992 in Khojaly town, NK during the First Karabakh war while trying to escape after the Armenians took control over the town) being a horror movie day every year in Azerbaijan, all the TV channels showing the same content: gruesome and ghastly footage of dead and mutilated bodies. “As a man I grew up with the idea to become a soldier, to take revenge, I call it “programming to kill”. ‘Love your mother, hate Armenians’ it was that basic.”

Jamal says he lost many friends because of their position during the war: “They say ‘we want peace, but…’ That sentence doesn’t work for me…”

There was Hermine Virabian, a 27 year old documentarian from Armenia.

“We saw many people those days [during the last Nagorno Karabakh war] who were talking about peace before and changed their ‘we want peace’ attitude to ‘we want peace, but…’ tells Hermine.

I knew Hermine due to her documentaries, and I knew she got the scholarship to do her Masters in Journalism in Georgia, in the same program I studied in with Azerbaijanis. She had to start her classes in September, 2020. Because of the COVID-19 situation the classes started only online and just a day after the war in Karabakh started. On October first I saw Hermine had gone to Nagorno Karabakh as a fixer for the journalists from French “Le Monde” and was under the shelling attack in Martuni city. When they heard the bombing they started running, the French journalists were injured, and a local accompanying them, Grisha Narinyan, who lost his brother in the April 2016 battles, died from the shelling.

Hermine says she wasn’t there out of patriotism, but rather to help the journalists to show the endless war and the suffering of the people who are going through it. As she describes it was not important to her if those people were Armenians, Azerbaijanis, or from any other nation.

When Hermine came back from Karabakh her husband was taken to the front to fight. Neither her own experience nor the fact that her husband was there changed Hermine’s pro-peace position. She says she was not criticized for her position as others who were talking about peace, she describes it as “having the right” to talk about peace in the eyes of the society. As she went through all of that herself no one could tell her she is able to talk about peace with Azerbaijanis because she doesn’t know how people suffered.

Hermine says seeing the hashtag #WeWillWin that was spread by thousands of Armenians on social media just in a day would make her mad. “The first time I saw it, I thought: are you playing a football match? It felt like this society wanted to be in that”, she says.

While remembering her school years and the history lessons Hermine smiles ironically “Those were not history lessons, those were classes of pathetic patriotism about the great Armenian nation. Those slogans we were learning couldn’t be questioned in school. Then you grow up, you meet Azerbaijanis, you see that they are people like you and you start questioning all your life”.

Hermine moved to Georgia after the war. She says some of the people who helped her go through the post-war stress were her Azerbaijani group mates. “We were like therapy for each other, we could see that our countries had ruined us from inside with the war and many other things adjusted to the war”. She remembers the “dolma party” they held with Azerbaijani friends in Tbilisi after the war “I was sitting at the table, already a bit drunk, and my Azerbaijani friend brought the plate with dolma (traditional dish both for Armenians and Azerbaijanis, grape leaves stuffed with rice and/or meat), at that moment everything about the war was very fresh, I started crying loudly after the first bite of the dolma. I was asking: why can’t we live like we do here, why we have to always kill each other?”

I met Togrul Hassanov, 22 (name changed for security purposes), already after the war, I knew he went to some dialogue programs with Armenians, and I wanted to understand what made him want to talk to the other side at such an early age. Togrul’s story turned out to be very much different from the stories I have heard before.

He told me he had studied in the USA for several months during his high school. The woman whose house he was staying in didn’t know anything about Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, but had an Armenian friend who was going with her to the same church. She once mentioned an Armenian friend to Togrul, and he told her ironically: “Probably she would be very happy to meet me”.

“Half an hour later my host-mother tells me that she invited her Armenian friend to the house. And she told her Armenian friend that she has a gift for her”, Togrul says laughing. While he was having his dinner, the kitchen door opened and the woman came in with her husband. Togrul’s host mother presented him to her friend “This is our new exchange student, Togrul from Azerbaijan”. Togrul laughs and imitates the reaction of the woman: “Oh!”

They started talking and the next morning Togrul’s host mother told him that Sevan (the Armenian woman) is going to come and pick him up to show around the city. “We had the best time ever, we went on hiking, seeing the city, and later on for the several months that I was there as much time I spent with my host-mother, I spent with Sevan”

Togrul remembers that his host mother had to leave the city for a while and he was going to stay with Sevan’s family. When he told his mother, her first reaction was: “No. They will kill you!”. Togrul organized a face-time with his mother and Sevan, so that they could talk. “They loved each other”, he smiles.

Going back to his childhood memories Togrul remembered a day when his brother and his cousins were playing in the house while he had an assignment and had to sit in his room and write an essay about Khojaly massacres. It was the manufacturing of hate; of fear and resentment, of blame, he says. Indeed, by the time he was in sixth grade, Togrul had harnessed this unconstructive dynamic in the most pragmatic and sad way. “We had to write about it every year. I started a business, I would write and sell the essays to others in my class,” he said..

Harutyun Badeyan, 27, was a participant in the same peacebuilding program I applied for after him, called “Rondine Cittadella della Pace ”an organization committed to reducing armed conflicts around the world and spreading its own method for the creative transformation of conflicts in every context. It aims to bring together people from different conflict divides who will live together for 2 years and will be willing to see the human beyond their enemy.

When I was accepted to the program Harutyun was back to Armenia because of COVID-19 situation in Italy, planning to go back to Rondine at some point. However there he was in September, yet in Armenia, writing a post on Facebook that he is going to war. I read his post with a shock, as he never was one of the typical nationalist guys I knew in Armenia, who would jump into the fighting from the first moment to show their patriotism. And neither was that the case. His post ended with telling his Azerbaijani friends that he loves them no matter what.

Harutyun grew up in Vardenis, where the memory of cohabitation with Azerbaijanis stayed fresh for a longer time, as he describes it. “My family had very close connections with Azerbaijanis, my father did his army service in Baku, and had very warm memories from Azerbaijan”. Harutyun’s uncle had a big farm in one of the nearby villages to Vardenis, which was once inhabited by Azerbaijanis. As a child he spent a lot of time there, and there was an Azerbaijani cemetery. “For us it was a place to play, it was interesting to look at the pictures on the graves, they had a cow or a horse sometimes on their gravestones, which is unusual in our culture”.

Harutyun recalls that his attitude towards Azerbaijanis changed during his army service (2012-2014), “I lost friends during my service time. They were shot by Azerbaijanis, subconsciously “Azerbaijani” became a synonym of “danger” to me”.

Two years later Harutyun went to Ukraine for a project, and met 3 Azerbaijani guys. They ended up becoming friends, and it turned out one of the Azerbaijani guys did his army service at the same time at the same place he was doing his service, only from the other side. “If we met 2 years before the project, during the service, one of us would not be alive, we would have killed each other, but we meet in a normal ambiance and we become friends”.

I was still wondering why Harutyun went to war. Almost a year later when I met him in Yerevan we talked about that. “I was not thinking that I am going to our historical land, to save the land, etc. I was there for the people. I had friends and relatives there, and I couldn’t leave them alone”, he said.

When Lala Zeynalova, 26, (name changed for security purposes) was born the First Karabakh war was already over, but the traces were there. Lala’s family was from Fizuli (one of the seven Azerbaijani regions taken by Armenia during the first war). Though her parents moved to Sumgait (about 31 km from Baku) before the war, they had relatives who became displaced because of the war. “My mom told me that we used to have a 3 room apartment, and 20-25 people living in those 3 rooms for some time.”

The first time Lala realized the war had caused something to her family was when she was 12: her dad took her to the grave of her grandmother from her mother’s side, and asked the Mullah to pray also for his mother’s soul. “Only then I understood that he couldn’t visit his mother’s grave because it was in Fizuli”.

She recalls that she didn’t have hatred towards Armenians but going to a dialogue program the first time they were all confused how to share the rooms, as there was the memory of what happened several years ago (an Azerbaijani serviceman killed a sleeping Armenian serviceman in Budapest, in 2004 during NATO’s Partnership for Peace program). “I had an Armenian roommate, a really nice girl, I remember looking at her and thinking: no, she wouldn’t be able to do anything to me”.

In one of those dialogues Lala met an Armenian from Nagorno Karabakh. “She was sharing the things her grandmother told her, and I was thinking “all this could be true, if they did what I knew to us, maybe Azerbaijanis also did this kind of thing? I later realized that humans are capable of everything… My uncle fought in the war, and I started thinking: “could it be that even my uncle did something?” I believe he didn’t but I would not even want to know”.

She told me they couldn’t say goodbye at the end of that program. “Everybody was crying. It was kind of an utopia that we were there, no one wanted to go back home”.

Ani Torosyan, 26, did her masters in Georgia. While describing the relationship between the Armenians and Azerbaijanis of the group she says, “We were like a family”.

She remembers that years ago Azerbaijani people were something unreachable in her perception. “I could imagine how people from any other ethnicity might look like, but when it came to Azerbaijanis, I couldn’t imagine them as humans. You can’t see those people, and you are told all those stories…you imagine them as some kind of zombies,” Ani says laughing.

She remembers one late evening: she was hungry and she was at one of her Azerbaijani friends’ house, and he started cutting potatoes to fry for her. “I was looking at the knife in his hand and remembering all the people telling me: ‘be friends with Azerbaijani but don’t throw the knife from your hands’, in that logic he could have killed me with that knife, but instead, he was cooking for me”.

She says all the parties they had in Georgia would end up crying and asking each other rhetorically why it should be like this.

Then the COVID-19 lockdowns started, and both Armenians and Azerbaijanis of the group had to go back to their countries. They were in their countries, with their societies also when the war started.

She says though during the war they were the same and they shared the same pain, when it came to an end, they found themselves on opposite sides of that pain, “Their pain transformed to happiness or relief, our stayed a pain. We could feel that our side lost and their side won”.

The transformation

Hamida Giyasbayli, a facilitator and a trainer who worked with The Imagine Center for Conflict Transformation for years, bringing together Armenian and Azerbaijani young people, artists, journalists, researchers, and analysts for dialogue and the opportunity to collaborate in the future, says for people from the older generation it is much easier when they meet someone from the other side because they still remember how to live together: “It meant a lot for us to work with young people who have been isolated from each other”.

She says especially now after the recent war that it had mostly been the younger generation that went to the war, it is important like never [to talk to each other]. “There was so much violence I think also because people never saw each other, the dehumanized image of the enemy continues up to now”.

Talking about her experience as a dialogue facilitator, Hamida says the participants usually go through a very hard transformation “People hear the other side’s narrative that is almost unacceptable for them, their identity is being questioned, all their life is being questioned”.

She says it has been difficult to work without support from local governments, people would be questioned, and there was a lot of “hunting” against peacebuilders and anyone who was participating in the dialogues.

“They go through this transformation, but they go back and face this enemy image again, it is not easy to go and say ‘now I have Azerbaijani/Armenian friends.’ It is the hardest question: what do we do next when we go back home? How do we accept this new reality that we are not actually enemies?”

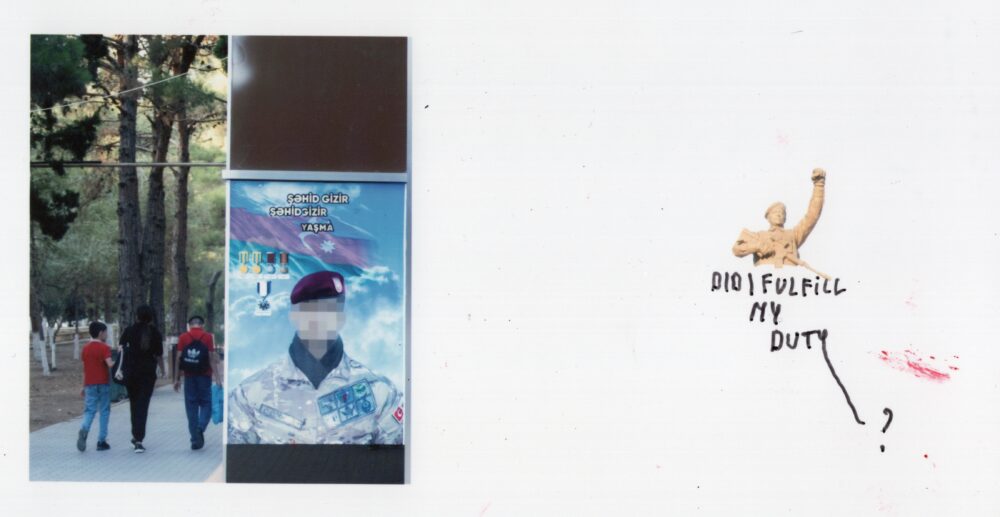

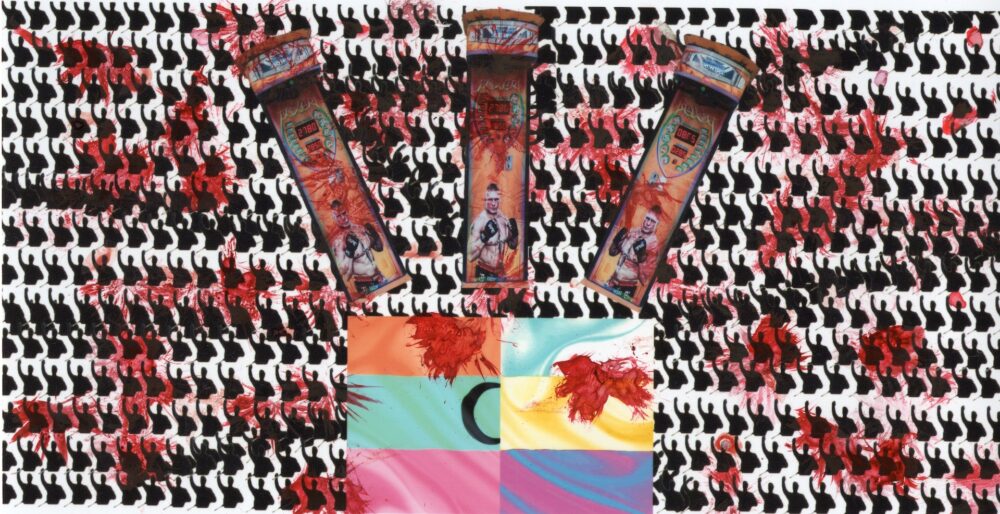

Visuals by Naila Dadash-Zadeh

Leave a Comment