Analysis

1 Jul 2020

New Perspectives for Tskaltubo

As a result of the war in Abkhazia about 10,000 of the approximately 250,000 Georgians who flew the conflict were accommodated in the sanatoria of Tskaltubo. As they had been living in Abkhazia for several generations, they lost all their property with the expulsion from their homes (cf. Zhvania 2010 for an overview on the privatisation of residential property in Georgia). This left them at an acute disadvantage when it came to rebuilding their lives; many remain living in the sanatoria to this day (cf. Mestvirishvili 2012 on structures of social exclusion in Georgia).

The article gives an overview on today’s Tskaltubo as a site of conflict around the interpretation of its material space between the resident displaced persons, tourist industry stakeholders, NGOs active in the town, and various groups of tourists. It is based on results of a geographical and ethnographic research project at the Institute of Geography at Justus-Liebig-University Giessen (Germany). Against the background of nearly 30 years of displacement this article will focus the socio-economically conflictual situation of the forcibly displaced persons living in Tskaltubo, whose continued residence in the sanatoria acts, in the views of most, as a brake on the development of a high-end spa industry seeking to attract international visitors.

The dramatical reconstruction of a well-established cultural landscape

Tskaltubo is located 15 km northwest of Kutaisi, Georgia’s second-largest city. In Soviet times, it was one of the union’s largest spa towns. The state-run system of health resorts which in the 1970s encompassed ‘approximately 6000 sanatoria, preventative health institutions and boarding houses hosted 13 million people each year (Schlögel 2017, 305, with reference to Kozlov 1979). The slightly radioactive thermal springs at Tskaltubo had seen it operate as a health spa as early as the nineteenth century. Between 1939 and 1955, under state health resort policies aimed at preserving the socialist labour force, the town received a number of complexes built in the historicising style of Soviet neoclassicism. A second wave of development in the 1970s endowed the town with further facilities, examples of Soviet classical modernist architecture.

Sanatorium ‘Tskaltubo’, built in 1931, with gardens in the foreground for subsistence agriculture

The forcibly displaced persons had to use of all the resources of this setting: parks once used for recreation by those taking cures became grazing pastures and gardens (see photo 1), trees were felled, and tables, chairs, flooring and counters from dining halls and refectories turned into firewood and cooking fuel (see photo 2) , the balconies of the rooms were all converted into kitchens (see photo 3).

Former concert hall of Sanatorium ‘Gelati’, built from 1953 to 64

Today’s four-star hotel Tskaltubo SPA Resort is the only Soviet-era facility now in use for its original purpose, having been occupied at the outset of the 1990s by paramilitary units who kept the forcibly displaced persons arriving from Abkhazia in 1992/93 from moving in. All other hotels currently open in the town are new builds, and only one of the formerly two centres for medical spa treatments is in operation.

Two facets of tourism – “Taking the waters” and “dark tourism”

After Georgia’s independence Tskaltubo soon drew the attention of investors from abroad who were aware of its Soviet-era history and its concomitant potential as a tourist location. But initially, international notice fell on Tskaltubo through the activities of foreign NGOs, due to the ongoing inability of the Georgian state to manage the forcibly displaced persons’ crisis exacerbated in 2008 by the second Ossetian conflict.

From 2004 to 2012 Georgia saw large amounts of foreign capital entering the country, and with it increasing numbers of visitors from abroad to Tskaltubo, first of all, backpacker tourists who have shared photographs and reports on their experiences on websites and blogs. These travellers produced the nostalgic narrative of a defunct bygone era, with the extraordinary possibility of meeting local people living in the wake of traumatic experiences and the loss of their worldly goods. We can refer to such tourism as ‘dark tourism’. On the other side, the four-star Tskaltubo SPA Resort hotel illustrates how this form of tourism insulates itself from the de facto reality of Tskaltubo as a refugee camp by employing security staff and charging high prices for the use of its facilities.

In 2012, the Georgian state commissioned the Swiss consultancy Kohl & Partners to draw up a market and technical feasibility study, whose findings led to the 22 former sanatoria going on the market from 2013 at prices ranging from 800,000 to 2 million euros. After prices fell by over half, some of the sanatoria were purchased by real estate companies from outside Georgia which subsequently sold the properties on, as did these owners in turn. None of these developments, however, generated the hoped-for boost to the area. The project was relaunched in June 2018 aiming at resurrecting Tskaltubo’s brand and turning it, in the context of the already known international partnership fund, into the ‘biggest spa destination in Eastern Europe’, indeed into a ‘Reborn Medical and Wellness Spa Capital’ (cf. Partnership Fund 2018, 5ff.). An overhaul of the town’s public gardens failed to usher in any significant developments, except for further resales of the four spa hotels already owned by foreign investors at that point. Today, fifteen sanatoria remain in state hands, and none of those sold have been refurbished.

Incipient and planned tourist use: The vision of Tskaltubo as a ‘Spa City’

Some of the accommodation now available in Tskaltubo points towards the gradual emergence of a new quality of spa tourism. This said, the advertising materials targeted at tourists issued by the Municipality of Tskaltubo (undated, a, b) name only the Tskaltubo SPA hotel as a former sanatorium currently in use as tourist accommodation; the remainder of today’s hotels, in line with the reality of Tskaltubo as a de facto camp for displaced persons, are new builds.

Since June 2018, the Tskaltubo Development Company has been intensifying its offerings for auction in a Tskaltubo showcased as a Soviet-era spa, having first commenced this endeavour in 2013. The ‘blurb’ text advertising the complexes for sale features the Soviet-era assignation of sanatoria and accommodation to various groups of workers, which highlights to potential purchasers the particularity of these objects in terms of their history (cf. in this context the almost complete reproduction of the plans of 1955 and 1983 in the ‘master plan’ for Tskaltubo’s development presented by Kohl and Partners, Partnership Fund 2018, 3-5, cf. Naumoviu et al. 1990).

As well as the re-establishment of tourist infrastructure, Tskaltubo is to see the resurrection of its Soviet-era institute of balneology in the form of a training centre for spa workers: ‘Tskaltubo should have an education center, which offers medical, wellness, hospitality-orientated and language courses to develop professional competences and high service quality within the local tourism industry […]’ (Partnership Fund 2018, 13). The Partnership Fund blurb makes explicit mention of the potential for integrating displaced persons into the labour market via vocational training (see Partnership Fund 2018). A critical caveat, however, is appropriate here, in that this is the only mention of the displaced persons to occur in the document, which contains no reference at all to long-term involvement of the local population in the town’s economy, nor to potential ways of reactivating Tskaltubo’s past as a domestic spa and leisure destination (cf. also Municipality of Tskaltubo 2018). The market analysis carried out by Kohl & Partners references international target groups only, drawing exclusively on general geographical considerations and economic data.

The response from the local tourism office to the plans to resurrect the 2013 initiative has been muted. Throughout the corpus of interviews, interlocutors avoid taking a clear position on the plans; what does become apparent is that there was no attempt by the state to engage the local authorities on the ground in the planning process. Except those sold previously, the former sanatoria are in state hands; the local administration is hence unable to access the built space on which Tskaltubo’s actual and potential repute rests. Accordingly, all locally-issued advertising material simply shows the prestigious facades of the sanatoria.

Anew state initiative, announced in October 2019, seems to be just a reframing of the thus far unsuccessful plans of 2013 as a new scheme (Dumbadze 2019). In November 2019, the Georgian Ministry for Tourism and Sustainable Development launched a new ‘six-point plan’ for the locality (Dumbadze 2019), revealing the multi-billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili, the former Georgian president and the current chairman of the country’s governing party, as its new driving force. Ivanishvili immediately put the plan proposed by Kohl & Partners back onto the table, promising to implement it if he were enabled to buy all the sanatoria at a symbolic price of 1 Lari (0,30 Euro Cents) (Sharashidze 2019). Although the outcome is still unclear as the 477 displaced persons’ families who remain living in the sanatoria are not due to move into new homes until 2021-2022, the relevant ministry has already announced that 2024 will see Tskaltubo’s ‘reopening’. The state’s claim that it will reach agreements with all stakeholders on the process is incongruent with Ivanishvili’s confidence that the decision has already been made in his favour (Sharashidze 2019).

Balconies converted to kitchens and other rooms in the Rkinigzeli sanatorium, built between 1948 and 1954; note the protruding makeshift chimneys

The bazaar of Tskaltubo permits a look on the social conditions of the displaced persons and the former community of Tskaltubo. It is the place where the people from Tskaltubo and the surrounding little villages meet. Additionally, it is a traffic hub where busses arrive and taxi drivers wait for customers. The bazaar building was constructed in the style of Soviet modernism with a lot of glass, iron and concrete (see photo 4). Its structure is more and more decaying (see photo 5). However, groceries, clothes, electronic devices and other convenience goods are sold on the ground-floor and on the first floor. Most of the vehicles in front of the building are in a condition which would prevent them from being driven in Europe. Due to high rates of unemployment, many men have been forced to become taxi drivers. They usually spend most of their days waiting. Fares are low (about 1 € per taxi and person for a ride from Kutaisi to Tskaltubo, 0,30 € for the bus ride). Still the poorest cannot afford the ride. The little bazaar behind the building illustrates the restricted financial capacities of the people from Tskaltubo. It shows what it means that more than fifty percent of the population in Georgia have to lower their household expenses by growing vegetables and fruits. There is obviously not much money circulating since many people are forced to live like that. Consequently, it is also hard for the traders to make a profit on the markets (see photos 6 and 7).

The bazaar building was constructed in the style of Soviet modernism.

The rear of the bazaar building shows more damages to glass and concrete.

About 12.000 of the people who had fled from the war in Abkhazia or been driven from their homes moved to Tskaltubo, about 4000 of them remained there up to 2018. In November 2019, the Ministry for Tourism and Sustainable Development referred to 477 families remaining in the sanatoria, an estimated 2000 individuals. Precise figures, however, are not available; other sources put the number of people inhabiting the sanatoria at 6000 (as of 2019; cf. Lomsadze 2019). The Georgian organisation factcheck.ge has documented the state’s clear failure to meet its target of moving 12,000 people into permanent homes in the years 2013-2016, noting that only 8,145 were rehoused in this period. Tskaltubo’s displaced persons are among those accommodated, in the 1992/1993 crisis, in what were known as Collective Centres (CCs), located, as well as in hotels and sanatoria, on former industrial complexes, in abandoned hospitals and sporting facilities. In 2018, such Collective Centres still housed around 43 per cent of displaced persons, with the remainder finding private accommodation – many going to their regions of familial origin in Svaneti and Kvemo Kartli in the nearby Georgian north – or returning to regions bordering Abkhazia due to mixed ethnicities within their families or for other reasons. Interviews I have conducted, the exploration of online sources on the general status of human rights in Georgia and the particular situation of displaced persons (see, among others, Janelidze 2014; Mouravi-Tarkhan 2009; Public Defender of Georgia 2016; World Bank 2016), and reports issued by the Georgian state on the management of displaced persons have permitted me to identify the following substantial issues facing this population:

· limited resources for households to improve their situations: a lack of safe land for subsistence agriculture, few possessions such as tools and household implements

· restricted socio-economic networks due to the experience of displacement and concomitant dis-location (cf. Aliyev 2013 and Rudaz 2015 on the importance of informal networks in Georgian life)

· insecurity and limitations on individuals’ ability to advance their futures; children and young people, people with disabilities and older people are particularly impacted

· health issues: a range of depressive and trauma-related conditions, addiction and substance abuse, disease due to poor living conditions and lack of hygiene, nutrient deficiencies due to food insecurity (cf. Mestvirishvili 2012 on structures of social exclusion in Georgia and Tarkhan-Mouvari 2008 for data and on forms of exclusion)

· limitations on mobility due to a lack of resources

Those who remain living in the former hotels, convalescent homes and sanatoria are subject to living conditions we must regard as precarious. My observations in the field and written records made during the three phases of fieldwork between 2017 and 2020 corroborate the fundamental assessment made by Mouravi-Tarkhan (2009) even ten years ago. Despite these difficulties, the residents of these complexes invest what they can in order to sustain and maintain their immediate surroundings.

The circumstances of life in Georgia are highly dependent on chance and tend to be outside individual control. The economic and social crisis which rocked the country brought with it a decline in skills which the poor state of the country’s education systems exacerbated. Poverty perpetuates itself down generations. In accordance with these difficult circumstances, labour migration, trade in home-grown produce at small-scale markets, and family and clan networks continue to be mainstays of economic survival in Georgia (cf. Gugushvili 2011, 16-18). The ‘Caucasus Barometer’ for 2019 reported that 15 per cent of the population found themselves with insufficient funds to feed themselves and their families daily in the course of a month, while 34 per cent, although they had enough money for food, could not afford clothing. The proportion of those dependent on the proceeds from selling the produce of small-scale subsistence farming stood at 28 per cent, and only 40 per cent received a more or less regular wage. Of those deemed low earners, 26 per cent reported needing a minimum of about 250 US dollars per month to cover necessary household expenses for themselves and their families and live ‘normal lives’; less than half (52 per cent) of the population have household incomes of 50-250 US dollars, and the average monthly old age pension stood at 50 US dollars (cf. Caucasus Barometer 2019). Pensions are crucial to supporting households within extended families among 59 per cent of the population. For some years, reports have been emerging of increasing levels of household debt in Georgia, accrued in what are usually futile attempts by families to lift themselves out of the poverty trap (cf. Lomsadze 2018).

The pensions of the old family members are crucial to supporting households within extended families among 59 per cent of the population (Caucasus Barometer 2019).

People’s resettlement from the sanatoria to more suitable and permanent homes faces the hurdle of the limited financial means available for this purpose to the Georgian state, which, beyond support schemes such as the EU’s refugee programme (for an overview, see European Union 2011) and help from NGOs, has very limited capacity to supply new housing for displaced persons. It was not until November 2017, four years after the commencement of the programme of state support for overhauling and resurrecting Tskaltubo as a health resort, that the last eight families remaining in the miners’ sanatorium, the town’s most prestigious building, could move to apartments in the Borjomi region (cf. report on Georgian government website agenda.ge, 11 November 2017). Many of those living in the former sanatoria and convalescent homes resist the idea of their resettlement; the infrastructure of the accommodation into which they are expected to move is often of a lower standard than that offered by the precarious circumstances in which they have made their lives in the last quarter-century. Reluctance to move is more marked still in the not infrequent cases in which the displaced persons are expected to fund the completion of their prospective apartments themselves. In most cases, these acts of resettlement, carried out without any supporting measures for improving or establishing infrastructure, amount essentially to the simple shifting of those affected from one place to another; the principal destinations of resettlement now, including Zugdidi near Abkhazia and the former spa town of Borjomi, were themselves initial localities to which displaced persons were transferred after conflict broke out in the country.

Results of several interviews in early 2020 with families in Tskaltubo point to an emergent trend for displaced persons to return to Tskaltubo after discovering that conditions in their new locations are often worse still due, for instance, to the lack of gardens close by for growing their own food. Further, some displaced persons hope that a potential increase in tourist activity in Tskaltubo might present opportunities for earning a living in construction or in service roles.

New and old plans for Tskaltubo

But none of the plans presented thus far takes proper account of Tskaltubo’s socio-economic specificities or seeks to bring civil society on board. One instance of this manifests in the failure to examine whether civil society stakeholders need generally to receive a right of veto over the sale of assets in public ownership on this sort of scale. The plans to date figure members of ‘civil society’ only as potential employees in a yet distant future, that is, as objects segregated from the current sphere of action and labelled with a particular function.

Alongside Tskaltubo’s built heritage, hopes of resurrecting the town as a ‘Spa Capital of Eastern Europe’ draw on the generally increasing numbers of visitors to Georgia as a whole (8,700,000 came in 2018; Agenda.ge 2018) and the town’s eminently reachable location close to the currently booming International Airport of Kutaisi, which has experienced a 40% increase in passenger numbers from 2018 to 2019 and processed 719,324 travellers between January and October 2019 (cf. BME 2019). Any and all marketing strategies drawn up by the Georgian state to date have of necessity relied upon the success of the rehousing process for the displaced persons to prevent initially interested foreign investors from taking flight again. Accordingly, the continuous aim for a number of years has been to issue upbeat reports on this process (cf. Agenda.Ge 2019, 2017); the precarious situation of the remaining displaced persons has found mention only in publications by NGOs (see above). Lyrical descriptions of Tskaltubo’s architectural and spatial potential linked to its Soviet-era glory days (see photo 8)have gone hand in hand with resounding silence on the actual numbers of displaced persons still living in the sanatoria, unable to escape the precarity of their set-up without assistance due to the severe limitations on their economic means.

‘Soviet-era’ classical architecture of the Sanatorium ‘Medea’, built from 1954 to 1962

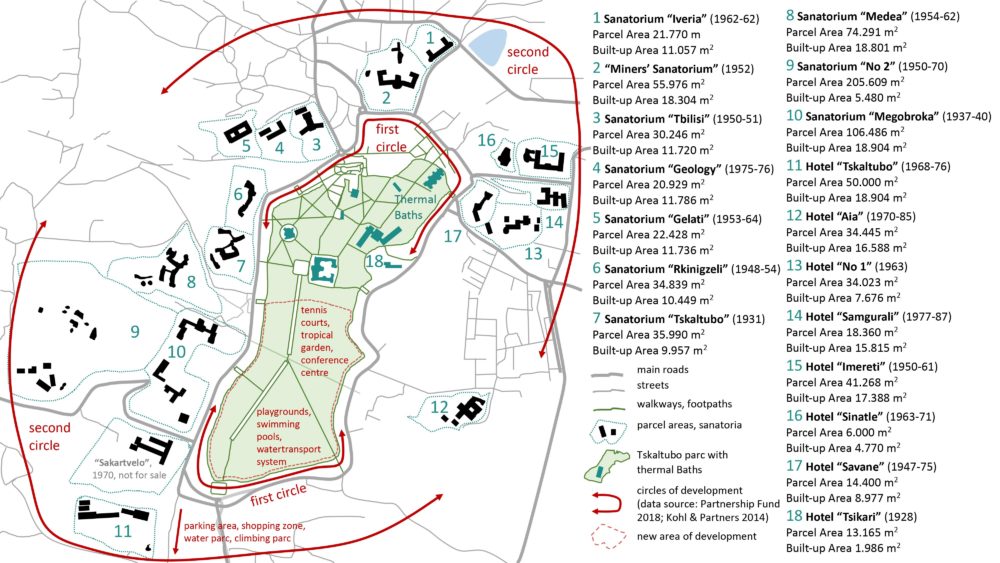

The first and then twice reactivated plans set out in the blurbs for the new spa development proceed from within to without following segmentation processes. The renovation of the town’s innermost area forms the starting point: ‘The sanitary zone and park were again the center of attention in the master plan. Concentric grid streets were planned around the park. The first central circle road around the park was for the visitors in the resort; the second main town circle was for the transportation of cargo and transport traffic in general. The third circle was planned to partially secure the second circle. This planning scheme defined Tskaltubo’s future functional and spatial structure for the next 30 years, and its impact continues even today’ (Partnership Fund 2018, 5; Kohl & Partners 2014, 24-27). In the year 2018, the centre area renovated in 2014 was already derelict or decaying once again, having received no momentum from that initial flurry of activity, directed as it was at the handful of tourists whose financial situation enabled them to pay the high-end prices charged by the two four-star hotels in operation.

Tskaltubo’s central area, with its former sanatoria and prospective developments

The area designated in the plans as located between the ‘second’ and ‘third circle’ was and is inhabited exclusively by displaced persons, although numbers have declined between 2014 and 2018; as such, there was nobody who could have used the renovated areas in the manner envisaged by the plans. It is evident that the displaced persons themselves have no interest in the conservation and renovation of this area; they are not the target group of these plans, which do not consider or mention their interests at all. Indeed, the ideal case, from the perspective of these renovation endeavours, would see them vacating the facilities; the company of displaced persons has no part in the tourist experience as thus designed. In other words, the segmentation of the displaced persons as a collective, in the plans drawn up by the Partnership Fund, causes them to virtually disappear (see also the literature aimed at tourists issued by the Tskaltubo Municipality, undated, a, b). The plans point to them as designated objects of reintegration (‘Start Reintegration IDP’, Partnership Fund 2018, 15), yet it is a reintegration assigned to take place outside the bounds of Tskaltubo, or on its outskirts, at purpose-built resettlement destinations with inadequate social, economic and educational infrastructure. In light of the prevailing conditions, resettlement, in this case, is likely to be detrimental rather than conducive to integration, taking place, as the plans will it to, in economically, socially and ecologically deprived spaces. It would exacerbate the segmentation and segregation already at work, thus reinforcing the idea of displaced persons as a collective unto itself, regardless of the diverse backgrounds of the individuals who comprise it.

It is evident, then, that the presentation of Tskaltubo’s Soviet-era sanatoria as its key potential asset essentially clashes with the strategy pursued by all development initiatives to date, an approach which appears to entail glossing over the current socio-economic situation and depicting Tskaltubo’s built space as empty and available for investors to take free rein. It is a strategy that compounds the local situation by seeming to induce state authorities to view the solution as removing the displaced persons from the space (cf. Municipality of Tskaltubo 2018, 8) and leaving all further action to private, non-state actors (cf. Dumbadze 2019, Sharashidze 2019), evidently in the hope that the benefits of tourism to local populations, as in other regions of Georgia, will materialise by the by without requiring any state-driven development strategies. All these measures have created thus far, however, is an emergent ghettoisation on the fringes of the prospective ‘Spa Capital of Eastern Europe’.

A look ahead

The public criticism expressed by Georgia’s four largest NGOs in response to the most recent initiative, the first substantial dissenting voices to be raised in the process, is in line with the findings of my analysis in this regard (cf. OSGF 2019). One particular point of disquiet with the plans is the state’s de facto admission of incompetence as revealed in its offer to transfer all Tskaltubo’s publicly owned assets to private individuals (cf. Jam News 2019). Further, the NGOs have pointed out that the plans are a further step along the path to the development of worrying monopolies which leave Tskaltubo wide open to abuses of power by individuals, particularly such individuals with extremely close links to a particular political party, as is the case with Bidzina Ivanishvili. As soon as such large-scale public assets are sold, the NGOs argue, the state loses any say in protecting and preserving the local built cultural heritage and, above all, relinquishes control of public access to that heritage and its associated use (cf. OSGF 2019, Jam News 2019, Lomsadze 2019). The interviews I conducted during the final phase of the research confirm the distrust, previously identified in a number of publications, felt by local stakeholders towards state institutions. There is an evident fundamental belief among this group that all opportunities for oneself or one’s descendants to experience state support for individual welfare – such as access to a spa cure – died with the Soviet Union, and the takeover of the local ensembles by an individual such as Bidzina Ivanishvili at least holds out prospects that one might attain a modest income from international visitors coming to the town.

Generally speaking, the potential for success of Georgia’s revitalisation as a tourist destination in the fight against the ongoing poverty in the country cannot be denied (cf. the detailed discussion in Metreveli and Gogorishvili 2016). Soviet-era tourist towns and cities such as Tbilisi, Kutaisi, Borjomi, Tskaltubo und Batumi are in a particularly felicitous position for developing an informal tourist sector, due to their residents’ experience of renting out rooms to visitors in that period (cf. Schlögel 2017, 305ff., on the overbooking of health, spa and holiday resorts both on an informal basis and by design). However, the interests of this stakeholder group are in opposition to those of members of groups like the displaced persons, who stand in our example in the way of Tskaltubo’s tourist transformation due to settlement and integration policies mishandled, frequently for political reasons, but also owing to a lack of resources. Other locations in Georgia likewise show evidence of such socially problematic tendencies attached to forms of tourism which, as visitor numbers swell, threaten the resources which drew the crowds in the first place (cf. Applis 2019 on the exemplary case of Ushguli in Svaneti).

A look forward reveals little indication of any certainty as to whether such a transformation stands a chance of sustained success. The comparative analysis conducted here of the data I have collected would appear to indicate that it does not. If policy proceeds in the same manner as it has thus far, the achievement of the objectives set in the plans for Tskaltubo’s future, however vaguely their hoped-for results are formulated, would seem to be impossible in the time thus far allotted; it is likely, then, that the funds invested to date by the state will be sunk costs. The difficult paradox here is the dual status of Tskaltubo’s built space as possessing outstanding potential, at least in principle, for a mass tourism typical of late modernity and simultaneously as standing in the way of that development. Severe declines in the value of this built space have resulted from years of consistently misleading information policies as regards socio-economic conditions in the town. Further, an evident inclination on the part of state stakeholders to regard the involvement of wealthy investors as a preferred solution to the area’s problems bodes ill for an appropriate consideration of the public interest going forward.

Bibliography

Agenda.ge (ed.) (2017): 8 IDP families receive new flats in central Georgia. http://agenda.ge/news/90508/eng (Date: 26 January 2020)

Agenda.ge (ed.) (2018): Eight million tourists visited Georgia in 2018. https://agenda.ge/en/news/2019/436 (Date: 26 January 2020)

Agenda.ge (ed.) (2019): More than 700 IDP families to receive homes in Tskaltubo, Georgian balneological resort. https://agenda.ge/en/news/2019/3037 (Date: 26 January 2020)

Aliyev, H. (2013): Informal Networks in the South Caucasus’s Societies. In: Caucasus Analytical Digest, 50, 2-6.

Applis, S. (2019): On the influence of mountain and heritage tourism in Georgia: The exemplary case of Ushguli. Erdkunde 73 (4), 259-275. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2019.04.02 (Date: 28 January 2020)

Dumbadze. A. (2019): Ministry of Economy Plans to Develop the Tskaltubo Resort According to a 6-point Plan. Georgai Today. http://georgiatoday.ge/news/18127/Ministry-of-Economy-Plans-to-Develop-the-Tskaltubo-Resort-According-to-a-6-point-Plan (Date: 26 January 2020)

European Union (ed.) (2011): EU Assistance to People affected by Conflict in Georgia, http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/delegations/georgia/documents/projects/conflictassistance_2011overview_en.pdf (Date: 26 January 2020)

Gugushvili, A. (2011): Understanding poverty in Georgia. In: Caucasus Analytical Digest 34, 16–18. http:// www.laender-analysen.de/cad/pdf/CaucasusAnalyticalDigest34.pdf (Date: 26 January 2020)

Kohl & Partner (2014): Technical Proposal for the Tskaltubo Spa Resort Development A report submitted by Kohl & Partner. Market & Technical Feasibility with Tskaltubo Vision Proposal. Kohl & Partners, Switzerland.

Jam News (ed.) (2019): Charity or racketeering? Ruling party leader Ivanishvili to buy up hotels in Tskaltubo resort town. https://jam-news.net/charity-or-racketeering-ruling-party-leader-ivanishvili-to-buy-up-hotels-in-tskaltubo-resort-town/ (Date: 26 January 2020)

Kozlov, I. I. (ed.) (1979):Zdravnicyprofsojusov SSSR. Kurorty, sanatorii, pansionatyidomaotdychaprofsojusov. (Izdanijepjatoepererabotanoeidopolnennoe). Moskva.

Lomsadze, G. (2019): Georgia’s billionaire boss to rebuild radioactive Soviet spa. Eurasianet. https://eurasianet.org/georgias-billionaire-boss-to-rebuild-radioactive-soviet-spa (Date: 26 January 2020)

Lomsadze, G. (2018): Georgia’s predatory lenders are punishing the poor. Georgian indebtedness has reached crisis proportions. And lenders take scant look at customers’ creditworthiness. Eurasianet. https://eurasianet.org/s/georgias-predatory-lenders-are-punishing-the-poor(Date: 26 January 2020)

Mestvirishvili, N. (2012): Social Exclusion in Georgia: Percieved Poverty, Perticipation and Psycho-Social Wellbeeing. InCaucasus Analytical Digest, 40, 2-5.

Metreveli, M. and Gogorishvili, I. (2016): Tourist production and regional development. In: Zbuchea, A. and Nikolaidis, D. (eds.) (2016): Responsible Entrepreneurship. Vision, Development and Ethics. National University of Political Studies and Public Administration. Bukarest, 184-198.

Municipality of Tskaltubo (2018): Economic Development Plan. Tskaltubo. Georgia. http://tskaltubo.gov.ge/document/%E1%83%98%E1%83%9C%E1%83%92%E1%83%9A%E1%83%98%E1%83%A1%E1%83%A3%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-%E1%83%92%E1%83%94%E1%83%92%E1%83%9B%E1%83%90.pdf(Date: 26 January 2020)

OSCF (Open Society Georgia Foundation) (Ed.) (2019): NGOs respond to Ivanishvili’s plans for Tskaltubo. Georgia. https://osgf.ge/en/ngos-respond-to-ivanishvilis-plans-for-tskaltubo/(Date: 26 January 2020)

Partnership Fund (2018): Medical and Wellness Spa Development. Partners: Kohl & Partners, geographic, Nola 7, Georgian State, http://imereti.gov.ge/res/docs/TskaltuboMedicalandWellnessTeaser2-Copy.pdf (Date: 26 January 2020)

Public Defender of Georgia (2016): Human Rights Situation of Internally Displaced People in Georgia, http://www.ombudsman.ge/uploads/other/4/4522.pdf (Date: 26 January 2020)

Rudaz, P. (2015): Institutional Trust and the Informal Sector of Georgia. Caucasus Analytical Digest, 75, 10-13 https://www.laender-analysen.de/cad/pdf/CaucasusAnalyticalDigest75.pdf (Date: 26 January 2020)

Schlögel, K. (2017): Das sowjetische Jahrhundert. Archäologie einer untergegangenen Welt. C.H. Beck: München.

Sharashidze, G. (2019): Exclusive Interview with Ivanishvili – New Opportunities for Georgian Business. http://georgiatoday.ge/news/18002/Exclusive-Interview-with-Bidzina-Ivanishvili—New-Opportunities-for-Georgian-Business(Date: 26 January 2020)

Tarkhan-Mouravi, G. (2009): Assessment of IDP Livelihoods in Georgia: Facts and Policies. Tbilisi, UNHCR.

World Bank (Ed.) (2016): Georgia – Transitioning from Status to Needs Based Assistance for IDPs. A Poverty and Social Impact Analysis. GSU 03: Europe and Central Asia. Report No: ACS16557, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/493981468030331770/Georgia-Transitioning-from-status-to-needs-based-assistance-for-IDPs-a-poverty-and-social-impact-analysis(Date: 26 January 2020)

Zhvania, I. (2012): Housing in Georgia. In: Caucasus Analytical Digest, 23, 2-5.

Leave a Comment